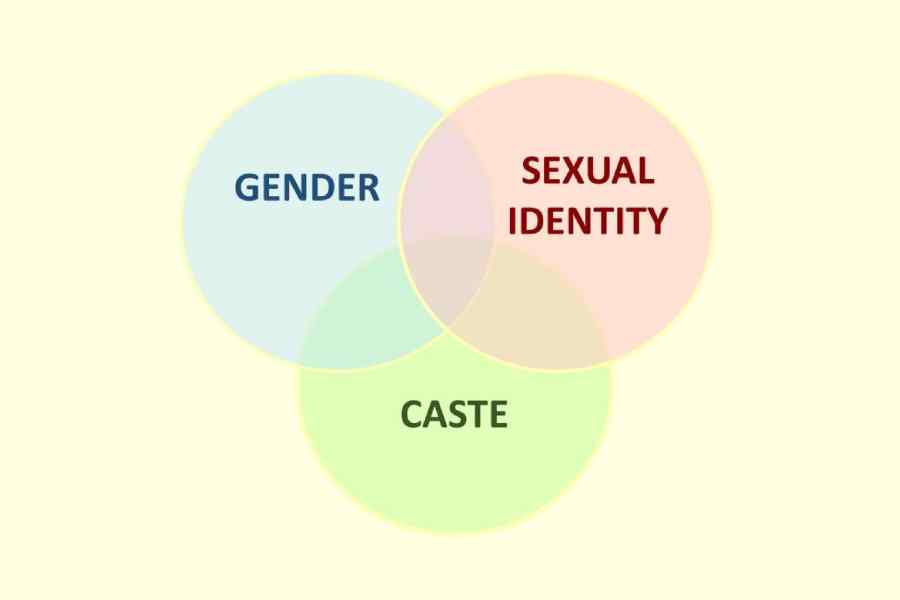

The concept of intersectionality has emerged as a comprehensive approach for analysing the intricate nature of oppression. In this piece, an attempt has been undertaken to untangle the intricacies pertaining to intersectionality.

The term, intersectionality, was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in a paper that argued that women’s issues need to be situated in a broader framework. The roots of intersectionality can be traced to the disenchantment of black women with the feminism advocated by white women. Black women felt that the issues raised by white women were not coterminous with those faced by them. At the same time, black women faced blatant sexism in the civil rights movement. This necessitated a two-pronged theory that could address the questions of race and gender.

In the Indian context, race can be replaced by caste. Every now and then, we witness stubborn insistence from some quarters, emphasising the alleged obsolescence of caste. It is believed that caste is a thing of the past and bears no relevance in the present world. In so doing, its proponents ignore the countless reports of violence against Dalits that come to the fore frequently. This line of thought also insists on separating the cases of violence against women from those of caste. This reasoning reflects a flawed understanding of what caste is and how it manifests itself.

In an article, Dipsita Dhar, a feminist activist, argues: “Four Dalit women are raped every day, there are cases where women are raped inside the police station as they go to file a complaint of sexual harassment, there are also cases where, even if rape charges are registered, the SC/ST Atrocities Act will not be brought [against them]... NCRB data shows the conviction rate for crimes against Dalits and Adivasis is much lower than the rest. What else is this if not institutional, structural bias built around caste solidarities between criminal, police and judiciary? That’s why Dalit women’s bodies can be made an easy site of violence: there’s no risk, no price to pay, the perpetrator is confident about the impunity, the social-political protection he gets by virtue of being from a ruling caste.”

Those who insist on separating the question of caste and gender often fail to gauge how deeply caste is ingrained in the Indian psyche. There are numerous instances of Dalit women being raped for daring to question the upper castes or for merely asking for a raise in wages. Sexual violence is a tool by which the upper castes feign their supremacy over Dalits. To treat such cases as a function of patriarchy alone is analytically stultifying. Moreover, in so doing, we, knowingly or unknowingly, give impetus to such criminality by failing to identify the unholy nexus between caste and patriarchy.

The analysis of violence on Dalit women must, in fact, transcend caste as a causal factor. Transgenderism, class, ethnicity and so on are factors that might not be as tangible as caste but are, nonetheless, significant issues. Grace Banu, a Dalit transgender activist, has, for instance, been trying to raise awareness about the invisibility of the Dalit transgender community.

The need for an intersectional approach to map the forces of oppression becomes even more important when the ‘progressive’ constituency exhibits casteist inclinations. Of late, many Dalit queers have been complaining about the discrimination they face in queer spaces. They are told to leave their caste identity at home and not bring it to queer pride events. Upper castes tend to monopolise spaces, undermining representation from socially disadvantaged groups. This holds true of queer spaces as well. Their propensity to be ‘apolitical’ is indicative of the fact that they are loath to let go of the privileges that have been bestowed on them.

This is where intersectionality becomes an important tool to understand that oppression is a function of a myriad factors.

Shashi Singh studies in Delhi University