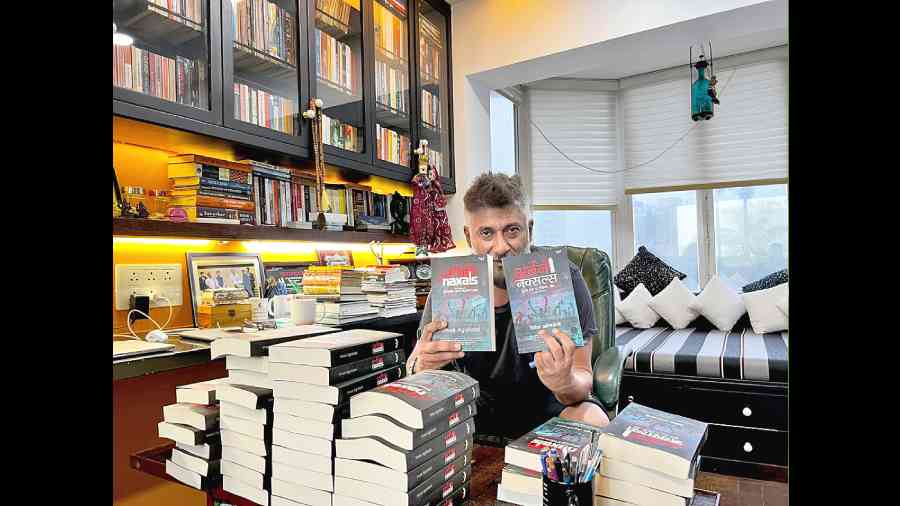

The film director, Vivek Agnihotri, has acquired a significant cult following in India on account of two significant achievements.

First — and this is his lesser claim to fame — he was the originator of the term, ‘urban Naxals’, an expression that has now entered the Indian political vocabulary to signify a clutch of committed, far-Left activists who operate undercover in society. Using the expression popularised by spooks, they would correspond with the ‘agents of influence’— prominent citizens whose real motives are masked in a cloud of respectability. Such people, be they corporate executives or university teachers, invariably feature in his films and play sinister roles. Indeed, his film, Buddha in a Traffic Jam, is almost entirely devoted to the phenomenon of urban Naxals.

Secondly, his film, The Kashmir Files, was unquestionably the Film of the Year for 2022. The spectacular box office success of this mid-budget film was undoubtedly significant, especially as it tried to depict real history in as realistic a manner as possible. More significant, The Kashmir Files was among the new genre of films that departed from the Left-wing narrative of India’s past. The extent to which this shift was triggered by the political and the ideological changes in the country after the victory of Narendra Modi in 2014 is for historians to assess. What can be said with absolute certainty is that a film depicting the attacks on Kashmiri Hindus in the Kashmir Valley and the mass exodus of that community from its homeland in 1990 triggered a storm in the country.

The reasons were obvious. When the ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Hindus from the Kashmir Valley happened in 1990, the media and the political class were slow to respond. With the government’s control over the area being contested by separatists, the hounding out of Kashmiri Hindus became a detail in a larger story. True, the Bharatiya Janata Party, which was keeping the minority V.P. Singh government alive with ‘outside’ support, raised the issue both in and out of Parliament. Unfortunately, and perhaps because of the BJP’s identification with the grim plight of the Kashmiri Hindus, a significant section of the opinion-making classes arrived at the bizarre conclusion that highlighting the Hindu exodus would lead to the communalisation of the Kashmir problem. Instead, there were attempts to suggest that the exodus was carefully planned by the state’s governor, Jagmohan Malhotra (who was later elected to Parliament from New Delhi on a BJP ticket), to discredit the separatist movement. Disingenuous Kashmiri politicians added their voice to this campaign of disinformation by appealing to the Kashmiri Hindus who had left to return. It was suggested that they would be protected by their Muslim neighbours.

Few, if any, took up the offer. For the past three decades, Kashmiri Pandits have become a community without a geographical base — very much like the Hindu Sindhis who came away after 1947. Being blessed with a tradition of education, most of those who fled with their lives have rehabilitated themselves all over India, but particularly in Jammu, Delhi and Mumbai. With the younger generation detached from the experience of their forefathers, the existence of Kashmiri Hindus in places such as Srinagar, Anantnag, Baramulla, et al, has been consigned to history.

In documenting this tragedy, Agnihotri tread on the toes of India’s intellectual establishment that views the country’s past as a happy confluence of different religious traditions, broken occasionally by interventions by narrow-minded bigots. This has been the dominant narrative since 1947 and Agnihotri, wittingly or otherwise, suggested that this state of idyllic bliss isn’t always true. In effect, he questioned the selective amnesia and the denial practised by those who have appointed themselves custodians of the India story.

At the heart of the conflict, and behind the familiar secular-communal binary, is a simple question centred on what popular history should incorporate and what should be consigned to specialist literature, if not buried altogether. Of course, determining what should be included and what kept aside is inevitably dictated by political compulsions. The British, when they ruled India, highlighted a history that conveyed the message that indigenous Indians have always been on the back foot when confronted by invaders. Simultaneously, the internal divisions among Indians were gleefully portrayed. In the first three decades after Independence, the emphasis, naturally, was on correcting this narrative and rehabilitating many of those earlier cast in the role of villains. Subsequently, from the 1970s, Left ideology entered the arena of historiography and shifted the emphasis, first, to dry economic history and, then, to discovering amity and syncretism in every sphere. A particular emphasis was on papering over the sectarian fault lines, especially when examining the histories of the Delhi sultanate and the Mughals. Even when it came to more recent history, the embarrassing history of inter-faith conflict and separatism was sought to be pinned on the divide and rule approach of the British.

The depiction of history in cinema has always been a very prickly subject, as was evident from the (sometimes silly) disputes over the film, Padmaavat. Even the blockbuster, RRR, was the subject of controversy in Telangana. Naturally, The Kashmir Files had its own share of bickering. But these may well appear like a pillow fight in a boy’s dormitory if Agnihotri undertakes his next ambitious venture. Speaking in Calcutta last Sunday, he announced that The Delhi Files would, in fact, be about the horrors of Partition in Bengal.

The tale of Partition in the East has always been very under-researched. Part of this was due to the modern Bengali intelligentsia’s conscious policy of forgetting those dark days. The story of what happened on the streets of Calcutta following the Muslim League’s Direct Action Day in August 1946 and the subsequent horrors of Noakhali has lived on in popular memory but has scarcely been commemorated. If Agnihotri challenges this denial with a film as powerful as The Kashmir Files, it will, of course, rekindle distant memories. But for a generation that is blissfully unaware of what happened just prior to Independence, it will prompt the question: ‘why weren’t we told?’

It is this question that the custodians of ‘progressive’ thinking fear the most.