As Afghans who failed in the desperate stampede to flee the country are forced to come to terms with their lot, their new rulers face an even more excruciating challenge. But in reconciling their austere ideology of denial with promises of a less illiberal dispensation, they can find a disingenuous exponent of the art of quietly replacing hoary institutions with monuments to their own glory in India whose drift towards some form of Hindu Talibanism is spiced with the populist political tactics of Europe before the Second World War.

Afghanistan’s pictorial history illumines the dizzy road to its present trauma. Elizabeth Butler’s poignant painting of reputedly the lone survivor of an invading force of 4,500 soldiers and 12,000 civilians Britain sent to the First Afghan War is a reminder that the American evacuation of August 15 with its echoes of Dunkirk (1940) and Saigon (1975) was by no means an isolated triumph. It was the first bloody nose Afghans gave to the world’s three mightiest military powers. The Soviets fled next, tail between their legs, in 1989; the Americans, who long ago distorted Tom Paine’s noble pledge “to begin the world all over again” into a formula for hegemony, brought up the rear. Even Afghans who abhor fanaticism and yearn for the constitutional democracy that the 1978 Saur Revolution devoured must thrill to the triple achievement.

While Jawaharlal Nehru hoped to promote a scientific temper by advising newspapers not to publish astrological forecasts, photographs suggest Afghanistan’s instrument of change was sartorial. A 1918 portrait of King Amanullah’s three sisters shows them in European frocks. A decade later, his beautiful wife, Soraya, the first Muslim queen to appear in public with her husband, faced the camera in short skirt and high heels, a wispy veil fluttering from the brim of her cloche hat in token concession to Islamic orthodoxy. Amanullah not only encouraged European attire but made it compulsory in the fashionable parts of Kabul, thereby playing into the hands of mullahs, tribal chiefs and the British who were accused of morphing pictures of the queen in scanty attire. Their outspoken 92-year-old daughter, Princess India (she was born in Bombay), maintains the burqa is “not an Afghan garment and is not even an Islamic garment” but that did not save Amanullah.

Other pictures more tellingly recall the Afghan elite’s trek to a modernity that the Taliban despises and denounces and which must have played a major part in the series of tumultuous events culminating in Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada being anointed supreme leader. It began in 1923 when Emir (previously only Sardar) Amanullah had himself proclaimed “His Majesty the King”, and climaxed two years later with a costume ball where everyone pretended that Afghan dress was as exotic as kilt and kimono, somewhat like the Indian fad of referring to indigenous garments as ‘ethnic’. Cultural posturing provoked protests in 1928 and, eventually, the rebellion of 1929 that overthrew and exiled Amanullah.

In the one photograph I have seen of the rising’s leader, a sandalled Tajik peasant, Habibullah Kalakani, he looks no different from any unkempt Taliban foot soldier even though he lived and died — executed actually — 65 years before the Taliban was born. Not much may have changed in the intervening years. When Amanullah’s great-nephew, King Zahir Shah, Afghanistan’s last monarch, and Queen Humaira visited India in the late Fifties, Her Majesty tiptoed (as if still in high heels) around Tipu Sultan’s palace at Seringapatam where shoes were not allowed. A friend in Mysore who acted as honorary lady-in-waiting said it was as if the queen had never laid a bare foot on Mother Earth and didn’t know how to. Despite Zahir Shah’s constitutional reforms, the ruling elite seems to have remained as estranged as ever from Asia’s arid reality.

Dynastic feuds, tribal strife, superpower stratagems and the tidal wave of Muslim resurgence were additional complications. Laced into them were whispers of highly-placed members of Ashraf Ghani’s regime making secret deals with the relentlessly advancing Taliban and of the Taliban cutting through administrative structures and political alliances by appealing to the 14 tribes “and others” that the Constitution mentions. The former evoked Indian memories of 1857; the latter warns of the mischief ahead if the 25,000 sub-castes into which our four main castes are supposedly divided really get going. That is without counting Dalits whose ritual status outside the hierarchy doesn’t mean they are strangers to caste politics.

The most significant picture is political. While Mahatma Gandhi’s loin cloth astutely identified the leader with the multitude, politicians in monarchical Afghanistan had to dress up, not down. Jackets, waistcoats and neckties were mandatory for those who attended the loya jirga or grand council in September 1928. My picture includes even a high-ranking courtier sporting the cutaway coat and striped trousers that dominated 19th-century European chancelleries but were last seen on Japanese dignitaries. Although a scattering of European felt hats can be glimpsed above the photograph’s bearded visages, there isn’t a single floppy turban in sight. Nor is there a woman in the group, save for Soraya herself enthroned with her husband.

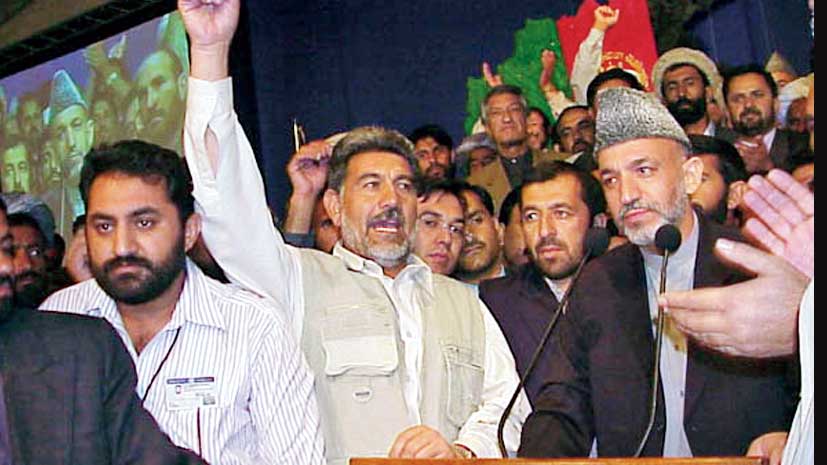

Times had changed by 2002 when another loya jirga chose Hamid Karzai in his tribal cloak and lambskin hat as interim president. Most of the men in that picture wear robes and turbans but a scattering of suits also testifies to the diversity of contemporary Afghan life. A number of female delegates confirmed how much Afghanistan had changed since 1996-2001 when the Taliban forbade girls to go to school and women to work. It claims to have changed but the first international leader to be granted the privilege of meeting Abdul Ghani Baradar, who will head the government under Akhundzada, was Ismail Haniyeh, whose Hamas controls the Gaza Strip. Predictably, Haniyeh drew a link between Baradar’s victory over “American occupation” and the continued “Israeli occupation of Palestine”.

A Taliban seeking international respectability cannot afford terrorist activities. It cannot even follow the example of Zahir Shah’s military assistance to the short-lived Turkic Islamic Republic of East Turkestan that Chinese Muslim troops quickly liquidated in 1934 but which China has never forgotten or forgiven. Even vandalism, like the 2001 destruction of the sixth-century Bamiyan Buddhas, is bound to alienate donors. With food running out and money in short supply, a landlocked, poverty-stricken Afghanistan denied access to its own foreign exchange reserves is forced to be circumspect. That includes not openly reneging on promises of inclusive governance, amnesty for adversaries, women’s rights and not to promote jihad.

All the more reason, therefore, for keeping the Taliban’s radical credentials shining through unobtrusive gestures like tampering with syllabi, discarding respected texts, promoting propaganda, adopting local equivalents of teaching astrology in universities, exalting sacred animals, and prescribing cow dung and urine for coronavirus. Parallels abound. Afghan warlords are medieval versions of the robber barons of modern industry. Afghan presidents are as fond of flamboyant apparel as democratically elected prime ministers. An overwhelming majority makes the minority inconsequential. Converting the India-built Parliament building into an Islamic council will avoid squandering millions of dollars on monstrous statues and the extravaganza of a Central Vista project or flogging the family silver through a monetization pipeline.

The emirate of Afghanistan was abolished in 1923. Reviving it means drooling over a fabled past that elsewhere supposedly witnessed plastic surgery and genetic innovation while sophisticated radar, superior to anything modern man knows, operated space shuttles. The wellspring for such fancies is understandable. But the movement is into a dead-end future. The Taliban has something in common with its Hindu cousin.