In the year 2009, the present prime minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, who was a vociferous critic of the Afghanistan policy of the then government of Pakistan, went to the United States of America to counter the growing perception that he was a sympathizer of the Taliban. Among his many appearances, he addressed a gathering of Pakistani Americans in Brooklyn’s Midwood area, which is called New York’s Little Pakistan neighbourhood.

That dialogue with the Taliban was the only way to bring peace to Afghanistan was the substantive part of his speech. Khan, who is from Pakistan’s Punjab but has Pashtun ancestral roots, appealed to Pakistani Americans to explain to fellow Americans the rationale behind his statements. Around 12 years later, as US troops near complete extrication from Afghanistan, the old and new contextual realities of the neighbourhood are determining the regional engagement with Afghanistan.

First, Pakistan’s foundational insecurities about Pashtun nationalism seem to be influencing its Afghanistan policy. Abdul Wali Khan, the son of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, had once said that he had been a Pakistani for 30 years, a Muslim for 1,400 years and a Pathan (Pashtun) for 5,000 years. In Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Pashtuns make up 78 per cent and 99 per cent of the population respectively. More importantly, Pashtun nationalism has an appeal on both sides of the 2,670-kilometre-long Durand Line, a boundary between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Moreover, many Pashtuns on both sides refuse to consider the Durand Line as a legitimate boundary.

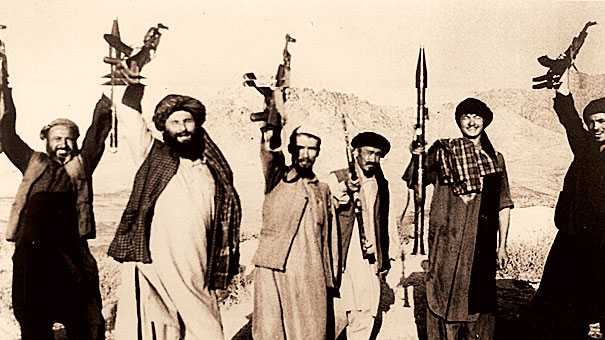

In this context, it is quite remarkable that even in the midst of the US-funded jihad against the Soviet Union in the 1980s, which is considered one of the factors behind the rise of the Taliban, organizations espousing Pashtun nationalism such as the Awami National Party continued their work undeterred. Now led de facto by the young Aimal Wali Khan, the great grandson of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the ANP has consistently faced persecution by the Pakistani State and presumed attacks by the Taliban for voicing religious moderation. In its opposition to the Taliban and their ideology, the ANP supported the Soviet Union action in Afghanistan in the 1980s and the 2001 US invasion.

In the last few years, another Pashtun-centric organization, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, has come into existence in Pakistan. In 2019, the Afghanistan president, Ashraf Ghani, condemned “the violence perpetrated against peaceful protesters and civil activists [of the PTM] in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan”, which the Pakistani State called interference in its internal affairs. In the current context, Ghani has alleged that there is Pakistani State support to the Taliban offensive against his forces.

Second, with the exit of the US military, the myriad regional, geographical, linguistic and ethnic realities are asserting themselves. Dari, colloquially known as the Afghan dialect of Persian, is the de facto lingua franca of Afghanistan for the majority, as it is spoken and understood by more than 70 per cent of its population. The Hazaras, the third largest ethnic group after the Pashtuns and the Tajiks, have an affiliation with neighbouring Iran in terms of their Shiite Muslim identity and cultural roots.

In the same vein, neighbouring Central Asian countries such as Uzbekistan and Tajikistan are directly influenced by Afghanistan as Uzbeks and Tajiks populate both sides of the border. These countries are highly controlled secular societies. In fact, even the use of social media was restricted till recently. The governing elite in the region is worried about the possible import of radical Sunni extremist ideology. In the last decade, Central Asian countries witnessed a large outflow of their nationals to fight in Iraq and Syria; they are commonly called foreign fighters of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. In the multilateral arena, the US and Russia have proactively cooperated in building regional counter-terrorism capacities, a rare geopolitical convergence between the two countries. In June, the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, had reportedly offered the US the use of Russian military bases in Central Asia for information gathering from Afghanistan.

Third, the Taliban’s political vision is the extreme and rigid interpretation of Deobandi Islam. Historically, Deobandi Islam has had an appeal among Pashtuns on both sides. The Deoband school of Islam started during 1866 in Deoband, which is close to Delhi. However, Pakistani scholars such as Akbar Zaidi have argued that Deobandi Islam in Pakistan has become different from its roots. This is on account of many factors, including the influence of the strict Wahhabism of Saudi Arabia.

In the last 20 years, devastating attacks within Pakistan, such as the 2011 naval attack in Karachi or the Pakistan army general headquarters attack in 2009, were carried out by the Pakistani affiliate of the Taliban, the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, which draws the core of its cadre from the Pashtun belt of Pakistan. However, in the post-2000 phase, several extremist organizations that claim to adhere to Deobandi Islam also sprung up. A notable example is the Jaish-e-Mohammad, which was founded by Masood Azhar, born in south Punjab’s Bahawalpur. Azhar, a Deobandi cleric and a declared international terrorist by the United Nations security council, was one of the three terrorists apart from the national of the United Kingdom, Omar Sheikh, and the Srinagar resident, Mushtaq Latram, who were released on December 31, 1999 and taken to Afghanistan as part of the Indian Airlines Flight 814 hostage deal. The JeM took responsibility for the Pulwama attacks of February 14, 2019 and was allegedly responsible for the attacks on the Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly on October 1, 2001 and the Indian Parliament on December 13, 2001.

Within Pakistan there had been several attacks by the JeM. On December 26, 2003, nearly a year after the JeM was banned, it made an unsuccessful bid to assassinate the then president, Pervez Musharraf. In 2002, Daniel Pearl, an American journalist, was kidnapped and later allegedly beheaded by Omar Sheikh. The Taliban’s growing strength in Afghanistan may enhance fund-raising and cadre recruitment of Deobandi extremist organizations across Pakistan. These groups are in competition with outfits such as the Lashkar-e-Toiba, which draws its inspiration from another regional conservative movement, that of Ahl-i Hadith.

In view of all this, the withdrawal of the US from Afghanistan and the ongoing ascendancy of the Taliban in the country are set to bring about greater regional volatility. The reality is proving to be a lot more complex than what was articulated by Imran Khan in 2009 as an Opposition leader.