What makes Charlie Chaplin’s films, especially Modern Times (1936), unique? To explore this, let us consider the navarasas. The artist uses each rasa either on its own or in combination with the other rasas. Groucho Marx, for instance, focused on just one form — comedy — whereas in Manmohan Desai’s films, one rasa follows another — happiness precedes pain or vice versa. Or, at times, one rasa is combined with another, as seen in the comic book series, Asterix.

Modern Times, however, is different from any of these works. It is unique in that it uses comedy to present tragedy. Sophocles’s Antigone or Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal uses tragedy to depict the tragic reality of human existence. Despite the dramatic elements, the homogeneity between content and form makes their formula straightforward. However, there is a disparity between content and form in Modern Times. Comedy, a positive form, is used to present harmful content. This use is as difficult as squaring a circle. It requires a deep understanding of tragedy and mastery over comedy and the ability to use comedy to present tragedy. Chaplin accomplishes this challenging task brilliantly.

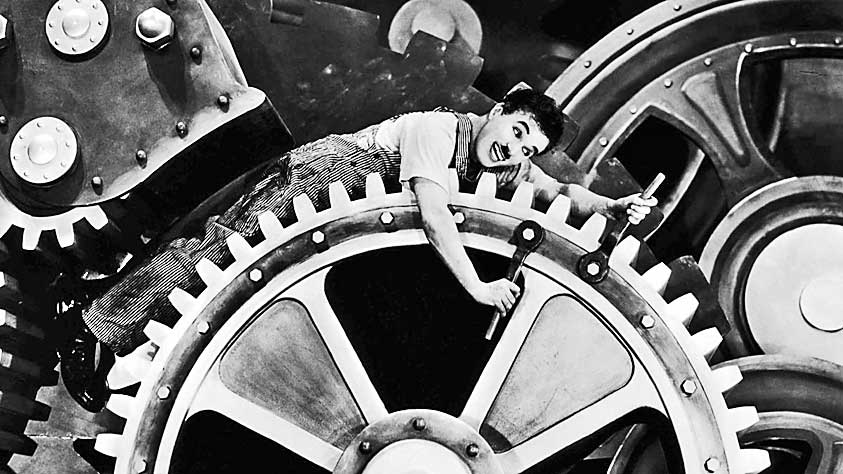

According to the opening title, the film narrates a “story of industry, of individual enterprise — humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” The machine is projected as the most outstanding achievement of human beings. However, Chaplin presents a contrasting picture of the devastating effects of industrialization on human beings. The brutal nature of the work at the factory leads to Chaplin’s character suffering a breakdown and being sent to an asylum. After his recovery and release from the hospital, he is arrested mistakenly and sent to jail. His presence at a mental asylum and a prison is, therefore, the direct consequence of working at the factory.

Interestingly, these symbols of tragedy are presented in the film not through scenes but through title cards. However, apart from a frame or two, Chaplin does not allow the tragedy to spill over into the film. He tactfully conceals the visible elements of tragedy, focusing on comedy instead. Following Foucault, asylum and prison are excluded from the film’s scenes: we get to know about them only from the title cards. Therefore, unlike in Desai’s films, there is no sequencing of the two contrasting rasas, tragedy and comedy, but their simultaneous use albeit at different levels. Chaplin handles this aspect of time pre-eminently. The tragedy is confined strictly to the titles, while comedy takes over the scenes in the movie. Unlike conventional tragedy or comedy, Modern Times deals with the dissimilarity between the two. The modern factory is a symbol of progress. At a surface level, the benefits of machines are attractive. However, the film narrates the invisible consequences of “humanities crusading in the[ir] pursuit of happiness”.

So how can one communicate these hidden consequences to those who are happy with the material comforts of industrialization? Those who are convinced about the advantages of the modern machine may not take the invisible consequences seriously. The problem before Chaplin was how to reach the audience and capture their attention. His success lies in his ability to keep his audience riveted to the screen and secure their attention by carefully packing tragedy with comedy. Engrossed by the hilariousness of the film, the audience receives the comedy-coated tragedy unaware of this underlying process. Viewed from this perspective, although generally considered a comedy, this film is, indeed, a tragedy par excellence. It is a tragedy of modern human beings who the lure of machines and industrialization may have initially enticed; but this, ultimately, leads them down a destructive path to asylum and prison.

Is Modern Times relevant today? Are there situations around us similar to the one depicted in this film? Let us consider the impact of subliminal advertising in television commercials. These ‘hidden persuaders’ use knowledge from cognitive and neural science, sophisticated AI technology and capitalism. For instance, is the ‘Skip Ad’ option on various social media platforms a bonus or a trap, given that attention towards a commercial is greater while skipping it? Is there a resemblance between seeing the ‘Skip Ad’ option but not clicking it or even clicking it and assembly line workers like Chaplin’s character mindlessly tightening bolts in the film? Can these invisible evils be creatively exposed using the conventional formula of homogeneity between content and form?

Chaplin is relevant in India as these sophisticated modern technologies are used both by non-literates and even by literates unaware of their impact. How do both creatively express this and secure their attention? Deployment of this unique combination by Chaplin also allows for exploring whether there are similar combinations available in Indian aesthetics or literature. Does the analogy of bitter medicine and jaggery by Abhinavagupta reveal similar shades of this unique combination? Is Shakuni a well-wisher of Kauravas or their disguised enemy? In case we do not find similarities in India, then we can consider emulating Chaplin.

A. Raghuramaraju teaches philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Tirupati