This is not the first time that an Islamist group has been responsible for massacring civilians in Sri Lanka. In the course of its counter-insurgency campaign against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, Sri Lanka trained a few Islamist outfits. The Home Guards, a paramilitary death squad comprising Muslims, assisted the Sri Lankan army in its operations. Another group called the ‘Islamic Jihad’ was behind the attacks on Tamil civilians in the late 80s and early 90s in the eastern district of Ampara.

This is also not the first time that Christians and their institutions have been targeted in Sri Lanka. In July 1995, the Sri Lankan air force bombed the Church of St Peter and St Paul in Jaffna. Joseph Pararajasingham, a parliamentarian from the Tamil National Alliance, was shot dead on Christmas eve in Batticaloa in 2005. Other Catholic priests who documented abuses of the State have also been assassinated.

The horrifying Easter attacks that targeted churches and hotels, leaving over 300 people dead, seem to indicate the emergence of a new player. The Sri Lankan State blames the National Tawheed Jamaat, a marginal Islamist group. The Islamic State has also claimed responsibility. The IS has released a video in which an NTJ leader is seen pledging loyalty to its cause. However, observers are also raising questions about the failure of Sri Lankan intelligence to act decisively on prior information that an attack was imminent. This has led to speculation that an internal power struggle or ‘external hands’ might have played a role in allowing the attacks to happen. Sri Lanka’s geo-strategic location does indeed make it a region of interest for local and global powers.

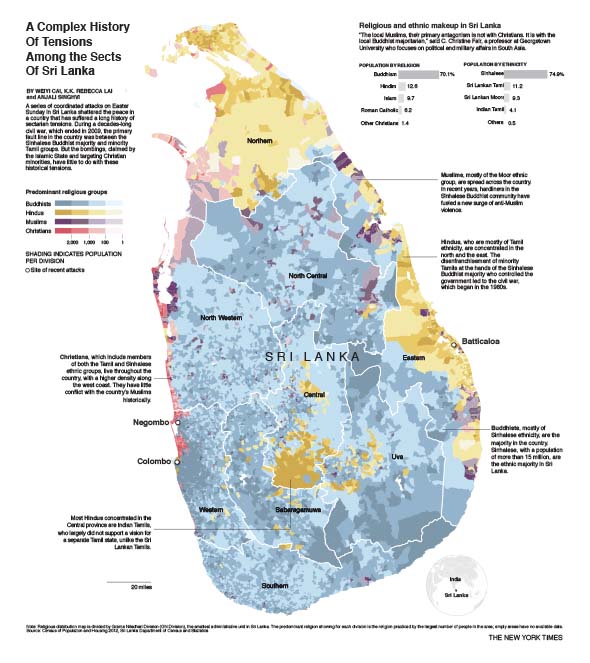

The politics of Islamism and its changing relations with the Sri Lankan State need a more insightful analysis in this context. The earliest pogrom that Sinhala-Buddhist fundamentalists conducted was against the Muslims in 1915. After Independence, the Muslims have tried to maintain an identity distinct from both Tamils and Sinhalese. Successive governments encouraged this so as to ensure that Tamil Muslims did not join the Tamil Eelam movement. Muslim political groups also found it more beneficial to negotiate with the State and Sinhala nationalists than Tamil leaders. This led to clashes with the Tamil militants.

Anti-Muslim prejudice returned to Sinhala nationalist politics after the Tamil insurgency was brutally suppressed in 2009. The anti-Muslim riots of 2014 and the 2018 saw Sinhala-Buddhist mobs targeting Muslim properties and places of worship. Muslims who had travelled to Gulf countries for work allegedly returned radicalized. Accustomed to targeting Tamils as enemies, Islamists now found a bigger foe in Sinhala nationalism.

However, the targets of the Easter attacks have not been Sinhala-Buddhists, but another religious minority. The scale of the bombings and the targeting of Western tourists lend credibility to the argument that there are links between those behind the recent attacks and the IS. Apart from the rather dubious reason that the attack was carried out in retaliation against the Christchurch massacre in New Zealand, one possible rationale could be that the Islamists wanted to demonstrate their strength to the Sri Lankan State by hurting its tourist economy.

The possibility of a Sinhalese retaliation seems remote. Given the fact that the majority of the victims were Christians, a sizeable number of whom were Tamils, it is unlikely that an anti-Muslim riot will occur. Reports say that stones were pelted at a few mosques, but the police have been able to prevent any escalation till now. However, the bomb blasts have given the Sri Lankan State an opportunity to deflect criticism of its treatment of the Tamil population.

Noam Chomsky had described Sri Lanka’s assault on Tamils in 2009 as a Rwanda-style atrocity; legal experts at the Permanent Peoples Tribunal in Bremen had termed Sri Lanka’s persecution of Tamils as genocide. Tamil diaspora groups have been lobbying at the UNHRC to investigate these charges. But they are likely to be cast aside in the public discourse as Sri Lanka seeks international cooperation to fight Islamist terror.