During our college and university days, my contemporaries and I had lived through politically turbulent times. Each one of us had sympathy for some political ideology or the other. Those who labelled themselves as non-political were reminded that their position itself reflected a particular ideology of defending the status quo. However, almost all of us fostered a belief that the world would be a better place when we grew up. This was not so much in terms of material wealth, but in terms of perceiving life as an experience where there would be more justice and fairness. Most of our parents, on the other hand, urged us to not get involved in politics but to focus on our studies and examinations and think about building a career that would give us economic security, if not wealth, and some social recognition. Many of us were caught in this contradiction. Needless to say, the overwhelming majority of my friends and contemporaries did build their own careers within the established structures of academia, civil service, the corporate world, and professions like medicine and law. The escape from the contradiction was by taking the easier route, due to parental and peer pressures, thoughts of starting a family, and, of course, the search for security and stability. I sometimes wonder what my contemporaries, who grew up during the Sixties and the Seventies, have to say now about their once cherished beliefs that it was possible to make the world a better place.

To change the world for the better, one would necessarily have to begin with a critique of the existing state of affairs in one’s own society and then stretch that critique to a bigger, global arena. For me, like many others, the most important problem was economic and social inequality. It was unfair morally. From the economic point of view, it stifled the potential of people who received a raw deal in life. It appeared that a few had everything and a large number had virtually nothing. Those in between were destined to struggle and slip but a handful did manage to get to the upper echelons of society.

The second major component of the belief that the world was remediable centred on poverty. There were enough economic resources to eradicate the deprivation in basic material needs. There were two routes out of the morass of poverty. One was the redistribution of wealth and opportunities. The other was through economic growth where the proverbial rising water level lifted all boats. But this was not very tenable as economic growth, historically speaking, seemed to have benefitted the rich much more than the poor. Hence, for me, redistribution was a better option.

The third issue that I (like many other friends) felt uncomfortable about was the distribution of power — political, social, economic. Those with financial muscle could control politics, social values, cultural norms, information, and even the world of ideas like education and research. This last aspect was very much on our minds when we looked at outdated syllabi, boring lectures, and examinations that tested our ability to remember stuff.

The above elements of the critique morphed into a fourth dimension — the world of freedoms and liberties. If we did want to change the world, we would have to have the instruments to do so. It required the freedom to think and formulate new ideas to bring about change and turn them into actionable strategies that would deliver results.

In the realm of ideas and actionable strategies, there would be alternatives that were bound to emerge. This is how political ideologies are shaped and honed. As soon as alternatives emerged, a new dilemma became clear. To what extent do we tolerate the alternatives and allow them free play or, to what extent do we fight and contest them to make our own worldview the dominant one? Hence, the fifth element that emerged was our concern for tolerance. To what extent should we tolerate different ideas and actions? Should we tolerate ideas and actions that are morally abhorrent to us? This is what philosophers call the paradox of tolerance. If we become fully tolerant, then we are likely to end up tolerating extreme intolerance.

Five decades later, as I contemplate our generation’s achievements and failures, I feel disappointed by what I see around the world. Economic inequality has increased sharply in my own society as well as across the world. The incidence of poverty, though less stark than before, is still substantial and widespread. Indeed, in some of the affluent nations, absolute poverty marked by joblessness and homelessness has increased. Yet national incomes have gone up by leaps and bounds and the marvels of technology are found in every walk of life. Power is significantly concentrated in the hands of the super rich — those who own the levers of influence to control almost every aspect of our lives. The oligarchy of the super rich works through the control of a political majority, or an authoritarian tyrant posing as an elected and, hence, socially accepted representative of the people. Freedoms and liberties appear to have increased in realms that hardly matter for social change — consumers’ choice is a good example of what I have in mind. In the more important realms, any form of dissent is increasingly discouraged, attracting stern consequences. Our lives are influenced by forces outside our control — the electronic and the social media, corporate advertisements, the lure of consumerism, State and non-State political violence, and the giant uncertainties of climate change, nuclear warfare, Artificial Intelligence, and the decay of democracy.

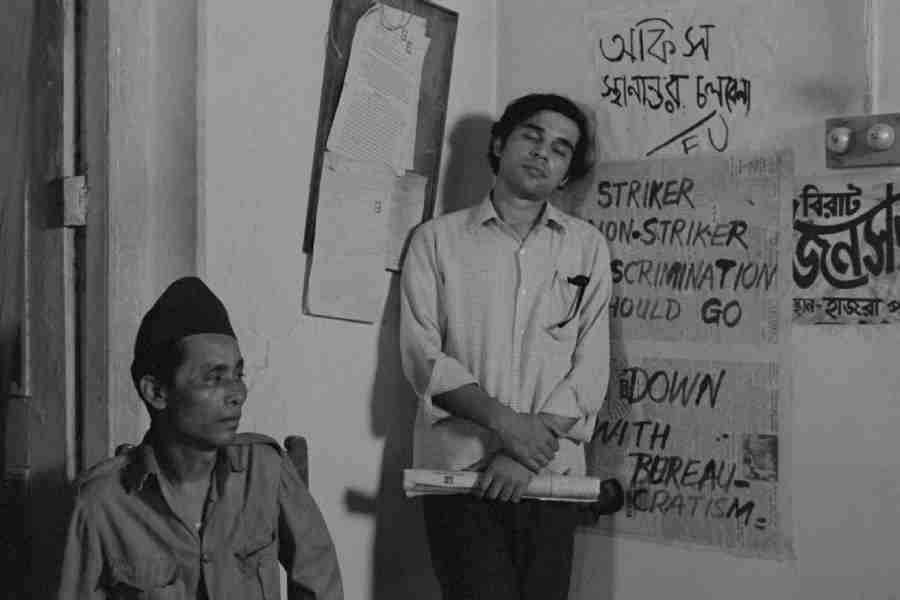

As new ideas have sprouted, so have control and intolerance. We live in a world where we have, as a species, lost the will to survive — it is a strange kind of myopic death-wish. Our sense of good and bad has become tangled as has our ability to decipher truth from falsehood. This was certainly not the world I had imagined, once upon a time many decades ago, when I was eighteen and living precariously amidst a generation where rebellion was morally acceptable, criticism was encouraged and considered intellectually stimulating, and differences were tolerated much more than it is now.

In old age, it is common to dream about the past. I have seen a large part of my own country and have had the opportunity to travel around the world and see other nations as well. I wish that the world was a better place than what it is now. Our generation must be held responsible for what transpired in the past five or six decades. We had the chance; we had the space; perhaps we could not muster enough courage and conviction.

Philosophers often encourage us to accept failures as a part of life. It is about individual choices a person makes, and then things do not work out as expected. It is indeed important, in such situations, to get up and move on. What I have described, however, is the collective failure of a generation to do what it believed in at one point of time. History is likely to give my generation a poor grade on the subject of making the world a better place; that is, if they still pursue history in the unknown land called the future.

Anup Sinha is former Professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta