In 1977, I had just finished school when I heard that Satyajit Ray was shooting Shatranj Ke Khilari at Indrapuri Studios in Tollygunge. I was an avid photographer, and it became my mission to get on the set and photograph the great man at work. After much trying, I finally found an ‘in’. Someone knew someone who knew the sound recordist, Narinder Singh, and, after meeting me, he agreed to get me access to the filming for a few days. On my first day, clutching my father’s good camera, I found myself being taken into the pitch-black labyrinth of the hangar-like studio. After a few moments, I saw a nebula of bright lights in one corner of the darkness and I was led to where Mr Singh was crouched over a Nagra tape recorder. “You can shoot, but just remember two things. Be aware and don’t get under anyone’s feet. Most importantly, the moment he calls ‘Silence!’ just remove your hands from your camera and don’t touch it again till he says ‘cut’. If your shutter goes off in the middle of a shot you’ll be kicked out and I’ll get in trouble.” There was no doubt about who the ‘he’ was.

Recently, I went to see an exhibition marking the Ray centenary. Given Calcutta and Bengal’s propensity for full shashtang worship of major cultural figures, it was good to see Ray’s work being presented with due rigour and respect but without the burbling hyperbole often found in such exhibitions. The wall texts put into context the wide range of illustrations, designs and writing that Ray produced along with his films, all without needing to tell us, yet again, how the great artist belongs to the international pantheon of film directors.

However, trace elements of the wellworn, hagiographical readings of Ray’s life are perhaps unavoidable, and they seep in via the various clusters of photographs on display. Taken by different photographers, there are pictures of Ray filming on location or on set, of him in his study and at official functions. Looking at these, it struck me that any history of photography in Bengal in the second half of the 20th century would be obliged to include ‘Ray photography’ as a unique genre in itself.

Quickly recognised as a protagonist-phenomenon of the modernity of the second half of the 20th century, Ray was photographed by dozens of photographers. Of the photographers who engaged in this copious Raydocumentation, people are most familiar with the pictures of Nemai Ghosh who dedicated his life and work to following Ray. In this exhibition, along with very few of Ghosh’s images, you saw some beautiful work by Tarapada Bandyopadhyay and also images by Sunil Dutt, Alok Mitra and others. Besides these local photographers in the show, Ray was also photographed by Raghubir Singh, Raghu Rai and Pablo Bartholomew to mention just three well-known names.

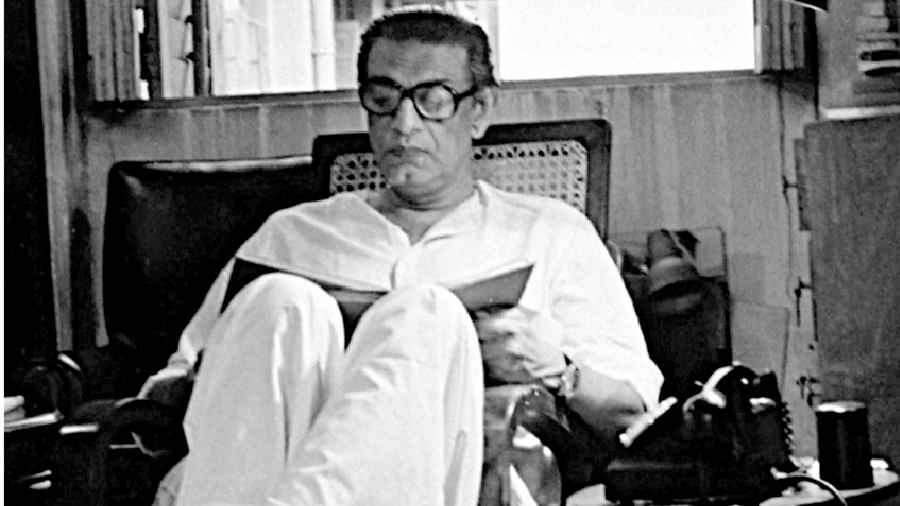

Perhaps not that different from trainspotters in Britain, this huge body of photographs has created a legion of what one might call Ray-watchers. Looking at the pictures, a seasoned Raywatcher starts to notice things: the similarities and the differences between the desk in whichever one of the flats near the Lakes and the now iconic study at Bishop Lefroy Road; there is the change of guard in the Anglepoise lamps, from mid-century silver to ‘70s black; the telephone instrument mutates from the wartime Bakelite model to the ‘80s rounded plastic; the armchairs transform, a footrest enters the frame; at some point, the paraphernalia for music composition is added next to the tilted drawing board; the east-facing windows are closed, then they are open, flooding in light. On location, the clunky filming equipment of the Apu Trilogy gives way to more modern kit; in the early production shots, you sometimes see Subrata Mitra or Banshi Chandragupta in the frame; the photographers acquire the new, extra wide-angle lenses for their SLR cameras and work those to death; in the earlier photos, Ray often partners a cigarette, occasionally a pipe, and there is always an ashtray in attendance, sometimes even on the camera trolley; in the later photos, these disappear, leaving just his lined face ravaged by ill-health.

By common consent, Ray was an exceedingly handsome man who cut quite a figure with his height and contained bearing. As a man who lived and breathed photographic frames, it’s no surprise how self-aware he seems to be whenever a camera is aimed at him. Yet, there is no projection of any excessive vanity — the ‘naturalness’ before the camera that he strived for with his actors seems to be ingrained in him as a subject. The pictures are unaffected but possibly not uncontrolled — there seem to be no pictures in the public domain of Ray ‘letting his hair down’, so to speak. This deeply private man would have been acutely aware that the aura and the publicity these photographs generated would aid him in overcoming the constant obstacles he faced in his projects, whether financial or from officialdom or other inimical forces.

Today, it’s difficult to imagine what the deeply private man would have made of the hullabaloo around his centenary. At the exhibition, given the recent barrage of Ray-centred media products, the mind starts to play tricks: with the pictures from the 50s and 60s — is that the film-maker, Q, or the actor, Jeetu Kamal, or Ray himself ? In one of the later photos — why on earth is Ratan Tata peering through an Arriflex camera?

One question that arises is what did the various photographers think they were doing? Once a few variations had come out, of the directorial pose, with or without the tobacco-delivery device, or the classic image of Ray concentrating on something in his study, surely there was nothing new to be gained by re-traversing such well-trodden ground? And, yet, you see different photographers over the decades trying to climb the same peak, more or less from the same few routes, almost as an act of pilgrimage.

After my few days on the Shatranj sets, I came away with no decent pictures of Ray. I did have some interesting frames of Richard Attenborough, some okay pictures of Tom Alter and Victor Banerjee but nothing very much of the man himself. Thinking back, I was simply too scared, too much in awe, to get close to him.

Looking at the photographs in the exhibitions, in publications and on the internet, one can see that this photography (what one could perhaps label the ‘Ray Safari’) was itself as much a part of the modernity of which Ray became such a Promethean icon — in a sense, this vast pool of Ray photographs can be seen as one celluloid tentacle of this modernity tenderly stroking another.