“Do you not want to use a walking stick, Dada?” I asked the 90-year-old.

Acharya Jivatram Bhagwandas Kripalani looked at me through his dimming yet un-fooled eyes and said, “No, I do not. I have a very short temper and if I had a stick…” I knew of his famous temper, as did just about everyone who had come in contact with him. But then I knew too that he also had his own, very distinctive, sense of humour — wry, acerbic shot through very often with a vein of pain, of sadness. And something even more valuable: Acharya Kripalani had a heart of the purest gold.

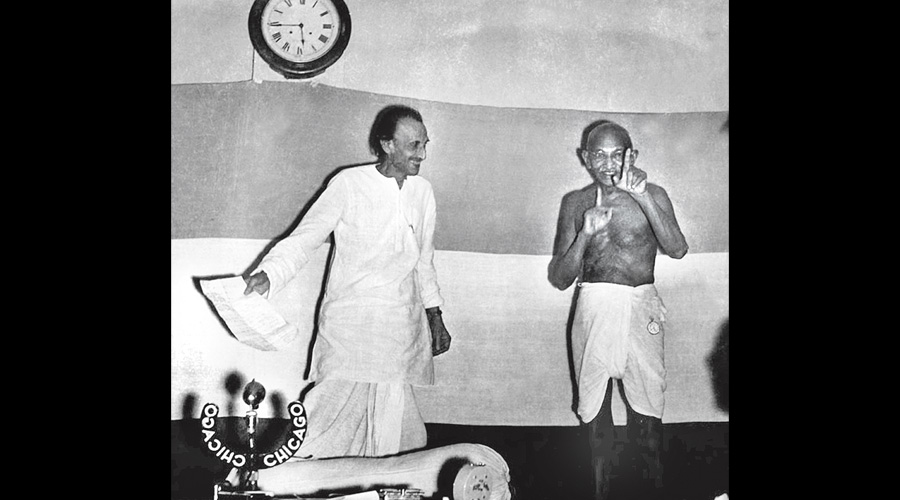

This conversation was in 1978. The veteran Sindhi leader was visiting Chennai for the first time after the defeat of the ‘Emergency’ Congress in the elections the previous year and the installation of the Janata government headed by Morarji Desai. He was sought after by politicians hoping to get something for themselves from a leader seen as having installed, along with Jayaprakash Narayan, the new prime minister of India and hugely influential with the new regime. These very people would have stayed miles away from the Opposition stalwart on his earlier visits. Certainly during the Emergency, they would not have been seen anywhere near his contrarian presence.

“Gandhiji”, Kripalani said, “turned dust to gold; we practise a contrary alchemy.”

Kripalani knew the game well. He had, after all, been in it since 1915 when he was all of 26 or 27 and Mohandas Gandhi, 46 or 47, freshly returned from South Africa, came to Santiniketan to meet Rabindranath Tagore. At that point, Kripalani was a young lecturer in English and History at the Government College in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. Intellectually vibrant, attractive in his casual appearance and even more in his artless manner, he was popular among his students. Can anyone with an all-too-easily provoked brain and a prickly tongue be popular? Yes, if the person is also transparently honest, utterly free of malice, and a stranger to personal ambition.

In 1917, when he launched his first satyagraha campaign in India in Champaran, Bihar, Gandhi was awaiting, in Motihari, what would have been his first arrest in India (but for a last-minute change of mind on the part of the administration). He was missing the quality of colleagueship he had known in South Africa. The struggle that was unfolding in India was going to be tougher, would last longer. Will he find the comrades he needed? That was when he received a letter from Kripalani, recalling their Santiniketan conversation, and asking him how he could help in the new satyagraha. Gandhi had ‘stumbled upon’ an exact equivalent of the colleagues from South Africa he was missing and hoping to find in India. “I read your affection in your eyes,” Gandhi replied to Kripalani, “in your expression, in your postures. May I be found worthy of all this love!”

In point of sequencing, from among the front-rankers in his ‘team’, Kripalani was the first of Gandhi’s political ‘discoveries’ in India, having met him, as I said, in 1915, within days of his return from South Africa. A member of the Congress Working Committee more often than not, the Grand Old Party’s crown kept eluding him.

Why so?

Was his patriotism not of the highest order? It could not have been higher. Was his sense of duty, his application to work, his stamina for suffering, sacrifice, any less than that of the other leaders? Absolutely not. Did he not spin his khadi as well as the others? He did, if anything, better. Did he not go to jail as often and for as long as the others? He did, indeed. Did he not enjoy the Mahatma’s trust as much as the others did? Yes, oh yes, totally, yes!

Then?

Jivatram Bhagwandas Kripalani had one small ‘problem’. He was Jivatram Bhagwandas Kripalani.

Follower he was of Gandhi; His Master’s Voice he was not.

Loyal he was to the Party; its flunkey he was not.

Abiding he was to its decisions; its ‘rolling boat’ of blotting paper he was not.

Interpreter he was of its policies; parrot he was not.

Colleague he was to his peers; crony he was not.

Dependable he was; drudge he was not going to be.

He was Jivatram Bhagwandas Kripalani.

Of Gandhi’s carefully considered choice of Nehru for his ‘successor’, Kripalani had his own interpretation. He said once (I quote from memory), “Gandhiji was confident of his ‘flock’ which faithfully followed him. But there was one sheep that kept running out of line, here and there and everywhere and Gandhiji kept following him here and there and everywhere to bring him back.”

Kripalani did not conceal what he felt about the competition among so-called Gandhians to out-Gandhi Gandhi. “They think,” he said in biting Hindi, “if Gandhi was gur, I am sugar.” He never aspired to or try to pass off as Gandhian glucose.

He was, in a sense, out-leadered. In charisma, Nehru was way ahead, in political intelligence, Patel, in intellect, Rajaji, in sheer learning, Azad, in that winsome quality of being mild-mannered and transparently sincere, Rajendra Prasad. And in terms of age, he was not going to be able to compete with the young Jayaprakash and Rammanohar. But in one realm, he reigned: the Kingdom of Pure Wit. And that was his because he bore no hatreds, no bitterness.

The Congress presidentship — then the howdah of the struggle — eluded him, year after year. The glow of approaching freedom lit up the others. Kripalani it silhouetted. And when the Congress’s crown did, finally, come to him, at the time of Britain’s departure from India, did Kripalani try to hog the arc-lights, out-do the eloquence of Nehru? Did he want to be in the new cabinet? He valued his unrepentant independence far too much to do any of that.

No party could hold him, no organization host him. He owed loyalty to his free mind and unsullied conscience. Of Kripalani can be said what Churchill said of Lord Rosebery: “He would not stoop, he did not conquer.”

Kripalani’s greatest moments lay beyond that moment of transition. Being in the Opposition came as naturally to him as being in Office came to his colleagues in the struggle. Bringing the Lok Sabha’s first-ever no-confidence motion in 1963 against Prime Minister Nehru (which he of course lost), Kripalani brought into the House a large bundle of telegrams from different parts of India in support. They poured down from his quivering hands as he moved his resolution charging Nehru with authoritarianism. Nehru sat through and heard the excoriation with a smile, not of condescension but of respect for the veteran and his veteran right.

That independence, that fearlessness, which is undeflated by reverses, unaffected by others’ seeming triumphs, does not chase after popularity, which seeks no reward other than a sense of duty diligently performed, is Kripalani’s political teaching.

And in all this, his heart remaining pure gold.

I will ever remember one cameo: Dada is seated in the first row of a concert by M.S. Subbulakshmi in Delhi. He is with his wife, the amazing Sucheta. She is a Congress leader; he is a pillar of the Opposition. It is winter. They are both wearing shawls — khadi, of course. They listen to the music rapt, holding hands. They could have been newly-weds, in the deepest love. I am seated several rows behind. And if memory serves me, one of the songs the Nightingale of India sings that day is Meera’s “Ansuvan jal sincha sincha prem bel boyi — Thus the creeper of love have I planted and watered it with tears.

The halls of power are not short now of temper. But of that which Meera sang, there is a drought.