Bei Dao turned seventy on the second of this month. Did the Chinese-American poet in Hong Kong and his friends celebrate the event? Could he — or they — have done so? Would this poet of quiet reflection and un-quiet expression have got himself to mark anything, even something as special as his seventieth birthday, in the conditions that now prevail there?

I doubt it.

What is that condition, in its core?

It is the condition of paradox or what in Sanskrit would be called antara-virodha. And Dao is, quintessentially a poet of antara-virodha, not political or ideological but human, poetic. But before I say more on Dao, I should reflect on his home city, Hong Kong.

Ever since Britain transferred its 156-year-old sovereignty over the island territory to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, Hong Kong has been a paradox — the late Latin para = distinct+doxa = opinion meaning ‘of a distinct opinion’ or ‘of a different hue’. The Sino-British agreement was one of a kind, altogether sui generis in negotiated treaties, under which the relinquishing power elicited an undertaking from the receiving power for a 50-year hold on any structural change. China agreed to keep Hong Kong ‘as it is’ for half a century — that is, till 2047. It would not impose its ‘socialist system’ on Hong Kong, nor any of its statist nostrums. Except in the matters of defence and foreign affairs, Hong Kong would be Hong Kong until 2047.

This was a bold, one might say, even audacious experiment in trusting a paradox to sit out its contradiction. Hong Kong was even before its joining PRC, something of an experiment — in social, economic and cultural terms.

With some 7.5 million inhabitants of diverse nationalities — Hongkongers as they like to call themselves — the 1,100 square kilometre-long island is about as densely and intensely active as a beehive but in very distinct hues or fragrances. As an alpha+world city it has been “a primary node in the global economic network”. It is the city with the largest number of skyscrapers in the world, the third largest (after London and front-ranker New York) concentration of individuals worth more than $30 million. And it has one of the highest per capita incomes anywhere in the world.

Hong Kong is about the celebration of wealth.

But its wealth gap is stunning. Hong Kong’s rich and poor live on different planets in the same tiny island. Housing has been dire for the poor, as also work opportunities and conditions — a conundrum.

Money remains high, skyscraper high, on Hong Kong’s mind — as the rich man’s goal for more riches, and the poor man’s and woman’s dream.

Dao, in an electrifyingly powerful essay, titled “Dwelling Poetically in Hong Kong”, translated by Lucas Klein, says: “... in Hong Kong, money is God, and blood pressure rises and lowers with the stock market, the moon waxes and wanes to prices of real estate; in Hong Kong, so as to reap the highest yield on their souls, the world’s richest capitalists meticulously manipulate sticker prices in supermarkets so they’ll be different on weekends from weekdays; in Hong Kong, a canyon separates rich from poor, and the city has a higher Gini coefficient than any other developed region in the world, yet no one fears upheaval from the impoverished; in Hong Kong, beneath the slick surface of equality is an entrenched class system, with the bottom of the pyramid made up of migrants, the unemployed, and foreign domestic workers.”

A different kind of upheaval, political and cultural rather than economic, has gripped Hong Kong these last few weeks.

When five Hongkongers associated with bookstores selling books by Chinese dissidents were arrested by Chinese authorities in 2015, there was great concern. And the recent proposal — as yet unimplemented and said to have been shelved temporarily — of Hong Kong’s chief executive since 2017, Carrie Lam, for legislation which will allow Hong Kong to extradite people to China as well as other countries has led to unprecedented protests including an ‘invasion’ of the legislature. Lam is in a more unenviable position than any head of government barring Boris Johnson. She cannot defend infringements on liberties without risking instant unpopularity at home and she cannot oppose them without risking ire in Beijing.

What Bei Dao thinks of all this, one does not know but he is bound to be troubled by it.

Dao was all of twenty-seven during the peaceful April Fifth Democracy Movement that unfolded in front of Tiananmen Square, in 1976. Reacting to the sponsored beliefs and belief-systems that were being unfurled at the time, Dao wrote a poem, “The Answer”, which spread like an underground fire in popular imagination. A quote from it:

Let me tell you, world,

I—do—not—believe!

If a thousand challengers lie beneath your feet,

Count me as number thousand and one.

On June 4, 1989, the day when the mass uprising at Tiananmen Square was suppressed, Dao was in Berlin as an artist-in-residence. Citing his advocacy of human rights, Beijing banned Dao from returning to China and denied permission to his wife and daughter from joining him.

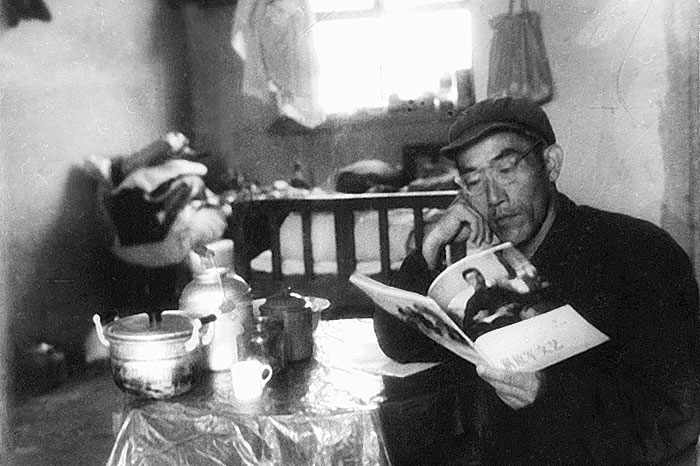

This led to his making a new home for himself in Hong Kong where he has been writing, photographing and from where he has been travelling extensively, celebrated worldwide for his work. And it has to be said that he has done all this from Hong Kong, an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China. Dao writes in what is called the “misty school” of poetry — obscure, elliptical, shadowy like Hindi poetry’s “chhayavad” (school of shades). It is about wanting privacy, reclusion. Not intrusion, apprehension, certainly not transportation. But his poetry is not to be searched for politics, for hidden political subtexts. But even in the “misty school” he has not made himself over-snug. He has his own sense of where that ‘mistiness’ becomes self-serving.

Dao is a poet, not a politician writing poetry.

The China of 2019 is not the China of 1989. And Hong Kong, for all the restrictions and intimations of more restrictions, is still Hong Kong with media that speak up and public squares that can resound with protesters’ voices. China has, besides, revoked its ban on Dao who has been ‘back there’ more than once, since. And, very likely, if the septuagenarian Dao gets the Nobel prize for literature which he well could, Beijing may surprise the world and applaud him.

But… to pose a bigger question: though he lives in Hong Kong, where does Dao dwell? In the article quoted from earlier, he has this also to say: “… to dwell is the state of being of the human, while the poetic is the attainment via poetry of a spiritual liberation or freedom; therefore, to dwell poetically is to search for one’s spiritual home.” And he tells us of his initiatives “The Other Voice”, a literary festival in Hong Kong where (to quote Dao) “Seven renowned poets from around the world and over a dozen Chinese-language poets from the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan came for a festival that attracted over two thousand audience members.” And he talks of how he is seeking his cultural positioning in Hong Kong and also Hong Kong’s own.

Whatever else happens in Hong Kong over the long road to the Sino-British ‘last date’ of 2047, one ardently hopes for “The Other Voice” to be the lingua franca of the island of “another hue”. In a world that is globalizing around money, clubbing around weaponry, ganging up in alignments of power-wielding against individualism, Hong Kong’s uniqueness in its paradoxes is invaluable.

Dao says, very pertinently for us in India, recalling the emperor, Asoka: “There are many principles in the world, and many of these principles contradict each other. Tolerance for the existence of another’s principle is the basis for your own existence.” Space links people and territories, Time keeps them distinct. Faith, not fear must join them. To be shackled is not to be together.