Occasionally, an event takes place which illuminates in a flash of light the appalling injustice amidst which we live in this world every day of our lives. Such an event changes the way we look at the world and leaves a lasting impact on our lives and on the lives of many others, even those located far from the scene of the event. The Spanish Civil War must have been one such event, for otherwise so many young persons from all over Europe and America would not have volunteered to fight in distant Spain as part of the International Brigade and sacrifice their lives.

In my lifetime, however, it was undoubtedly the Vietnam War that was such an event. It radicalized thousands among the literati, the result of which was the arousal of an enormous interest in Marxism all over the world. This interest in Marxism had nothing to do with the Soviet Union and the traditional communist parties, since the appeal of traditional communism had faded by then among the youth; and notwithstanding the obvious sympathy that this Left upsurge had for the revolutionary positions adopted by Mao Zedong’s China and the breakaway Maoist groups that emerged everywhere as a sequel to Mao’s split with Moscow, it generally steered clear of these groups as well.

The year, 1968, was particularly crucial. In May, there was the workers’ uprising in France which got closely linked to the students’ movement that was occurring simultaneously; the workers occupied factories all over France as the students were occupying universities. And then there was the Tet offensive in South Vietnam where the Viet Cong stormed Saigon and even occupied the US embassy there, precisely at a time the United States of America was claiming success in the war; the offensive made clear to the world that the Americans could never win the war, although the war itself was to drag on for another seven years.

As student radicalism acquired intensity, revolutionary literature poured out from publishers who smelt a profitable opportunity and got into the act. Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, Rosa Luxemburg’s Anti-Kritik, Bukharin’s critique of Luxemburg, all classics that would otherwise have remained confined to obscure library shelves, suddenly flooded the bookshops along with Pelican paperbacks of the works of Frantz Fanon, Paul Baran, Paul Sweezy, Andre Gunder Frank and a host of other writers.

There was a parallel upsurge in creativity in the visual arts, with cinema leading the way. Everywhere, however, there was a desire not just to produce excellent creations but also to contribute in some direct manner to the revolution that appeared imminent. I do not know the mood in India at the time since I was away, but among many Indian students abroad there was a strong desire to return to the country and contribute in some way to the revolution. Given the distance of the Left upsurge from the pro-Soviet communist parties and the cautious stance, despite a certain degree of fondness, towards the pro-Chinese breakaways from these orthodox parties, the few communist parties in the world that had adopted an independent course — independent of both Moscow and Beijing — appeared attractive; indeed the Vietnamese Communist Party itself was one such.

For many Indian students radicalized by these developments and wanting to return home to contribute in some way to the cause of the revolutionary struggle, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) appeared an attractive option. The CPI(M), in turn, organized a set of annual conferences around that time where the party’s top leadership (at least two to four politburo members at each conference) interacted with Left intellectuals, including those returning from abroad, in open, no-holds-barred discussions spread over several days. I remember at least three such conferences, one held at Madras Christian College, Tambaram; one held at the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute, Mumbai; and one at the Indian Institute of Public Administration, Delhi. Thus, the ‘Vietnam generation’ of returnees drifted to a large extent towards the CPI(M) and, to a lesser extent, towards the various Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) groups, although many, of course, did not join any political party but remained committed to the Left cause in their respective spheres of professional activity.

With the passage of time, the Vietnam generation of returnees has now grown old. They are now in their seventies and early eighties. The passing away of some of them is to be expected in the normal course, but Covid-19 has been particularly severe on them. The month of May saw the passing of two such stalwarts.

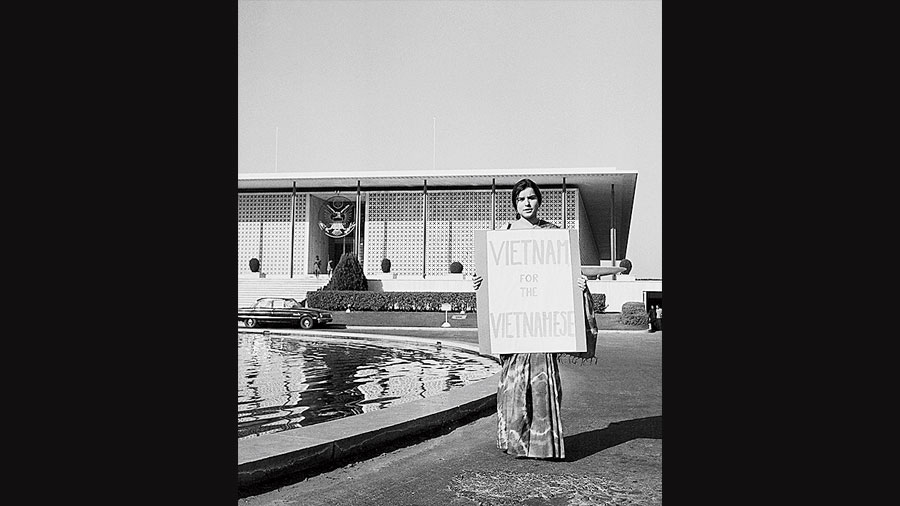

Ranjana Nirula was one. She came from an affluent Punjabi family, her father being a doctor who worked for the United Nations. She went first to the United Kingdom and then to the US to study about differently-abled children and how they should be cared for. While in the US, she became active in the anti-Vietnam War movement. Coming from a prosperous background, she had never had any contact with Left politics before. Exposure to Vietnam not only radicalized her but also changed the course of her life. She returned to India and became a full-time activist of the CPI(M). She worked for the trade union wing of the party (Citu), took an initiative in organizing women workers, edited — almost single-handedly — the journal of the Co-ordination Committee of Working Women, and was a founder-member of the All India Democratic Women’s Association. Right until the end, she was active in the women’s movement, especially the working women’s movement.

The other stalwart who passed away in May was Mythily Sivaraman. Slightly older than Ranjana, Mythily had a job at the UN that she decided to give up and returned to India to become a CPI(M) activist. When the Keezhvenmani massacre of Dalit agricultural labourers took place, she was among the first to visit the village to report on it and draw the attention of the world to the gruesome carnage that had occurred. Her visit to Keezhvenmani was an act of immense courage for she was taking on the might of the landlords and her reports on the event were both moving and brilliant. Mythily was an outstanding public speaker and a firebrand trade unionist; but she too moved eventually to the women’s movement and was a founder-member of the AIDWA where she remained active until overcome by age-related debility some years ago.

What was striking about both these activists was their abiding faith in the possibility of creating a better world. When the revolution is no longer on the horizon as it once appeared to be, there is a tendency on the part of those who had once been activists to settle down to a routine existence, going through one’s communist chores but lacking the fire in their bellies. Both Ranjana and Mythily retained their faith till the very end. This was no doubt because of the strength of their theoretical convictions; but I believe that the strength of these convictions arose from their exposure to the Vietnam War. Any system that could inflict such a savage war on a desperately poor country whose people had endured decades of brutal colonial exploitation and could even envisage bombing them “back to the Stone Age” cannot possibly be an enduring one; its transcendence is inevitable. They acquired this conviction and died with it.

Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Economic Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi