Sociological categories are not invented; they are born. They emerge out of the womb of a dynamic society bawling for attention. As categories, they are both archetypes and caricatures, they capture the real and the hyperbolic in what the German sociologist, Max Weber, called an ideal type. He described it as a one-sided accentuation of reality that sensitizes you to trends and futures. A distorted lens that enables you to see the stability and continuity in the dynamism of the social world.

The world of the migrant and the refugee created many new archetypes. American sociology is replete with them. The sociologists, Robert E. Park and Everett Stonequist, created the idea of the ‘marginal man’, a migrant who mediates two cultures, a fold between two kinds of experiences and memories. Indian sociology, too, discovered an archetype, which points to new kinds of aspiration and power. The NRI as a creature is a fascinating collage borrowing from older composites like the Anglophile. The Anglophile is a creature from a colony who loves the mother culture while is ambivalent or contemptuous of his own. The author, Nirad C. Chaudhuri, was a great anglophile. Yet, his wonderful work, The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, is one of the most classic studies of childhood. I remember my teacher, the sociologist, André Béteille, telling me a story he had heard from the sociologist, Edward Shils.

Niradbabu loved England, but he never visited England till he was in his late fifties. He arrived in London, was picked up by a cabbie, and he started issuing detailed instructions signaling a familiarity with the city. Niradbabu, of course, had memorized maps of the city. In a few minutes, he and the cabbie were at loggerheads, with the cab driver protesting at being accused of not knowing his city. After a few acrimonious rounds, the cabbie discovered that Chaudhuri was talking of a London before the War, before the bombs had erased large parts of the city. His cartographic knowledge of London was out of date. Chaudhuri had to reluctantly concede his error.

The NRI does not quite fit the colonial categories of the Anglophile and the Orientalist. He enters the world of ideas in a more material way. He is an aspirational, upwardly-mobile creature who leaves home to seek a more affluent and opportunistic world. He seeks success and he is defined by this success and its aftermath. Success is the sign of grace and the NRI, like Weber’s protestant, would feel identity-less without it. In that sense, he is a middle-class invention.

The NRI must smell of success and the perfume of success. This can have poignant consequences. One is reminded of an R.K. Narayan story of a worker who returns from the gulf oozing stories of conspicuous consumption. He was once an ordinary labourer in his Kerala village. He impressed his old mates. Success always allows for envy and celebration. Narayan then relates that later he flew to the Gulf. While waiting to change planes, he visits the rest room. As he steps in, he sees his old neighbour in a bright uniform cleaning the toilets. They pass each other in quiet silence. The NRI success must be more obvious and boisterous. Subrata Ray, my college mate, told me of the sardar at the Plaza theatre in Delhi, waiting restlessly in line. As his turn comes, he spanks the money down and says, “Give me five of the best.” Success and wealth need an audience; otherwise they feel abandoned and impoverished.

There is an economic power to the NRI which is obvious. There are many villages in Punjab which survive solely through the remittance economy. There is something about the puritan ethic about the NRI, a sense of dedication, even austerity, as he makes good. As a middle-class professional, he is India’s pride in America, one of the highest earning minority groups, easily challenging the Chinese and the resident Jewish community for the trophies of academic excellence. In fact, one of the rituals of academic excellence that India celebrates is the Spelling Bee where children of NRI families spell out complex words to retain the trophy. Competition is crucial for the NRI regardless of whether it is the Nobel or the Spelling Bee.

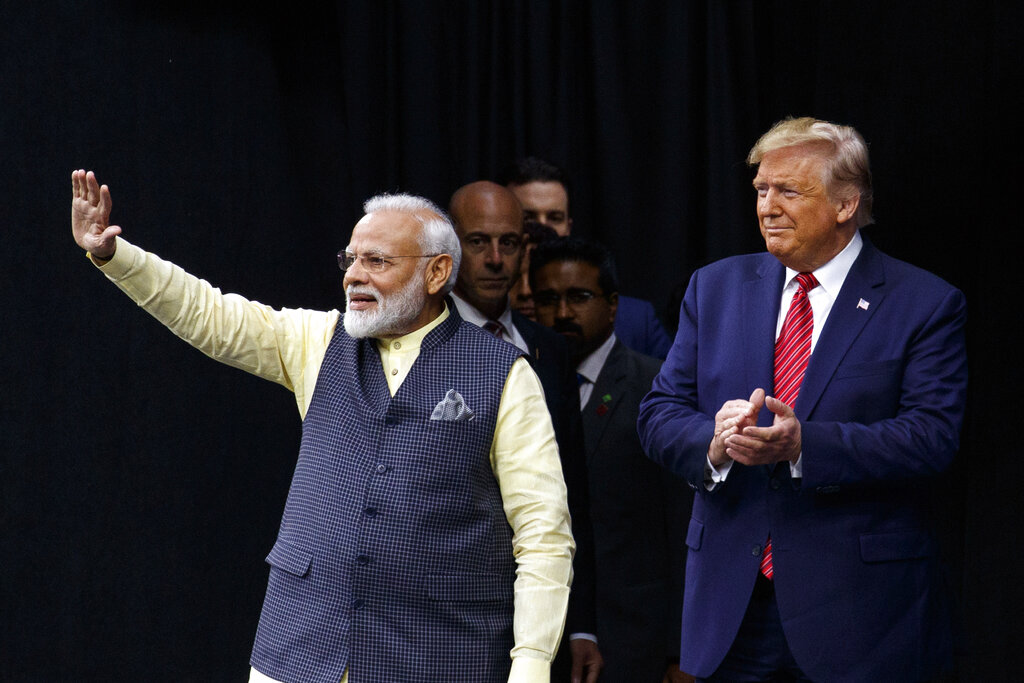

The middle-class NRI, literally as a geek, conveys an intellectualism, a professionalism, a table manners of the intellect that India celebrates. Our current prime minister, Narendra Modi, dotes on their support and, during his early years, loved the political support of the NRI and the shows they invited him to at the Madison Square Garden. The NRI loved Modi for decisiveness, his passion, his celebration of their success, his masculinity. Doves in the United States of America, they could be hawks at home, displaying a hawkishness and belligerence which Modi was grateful for. It is they who conveyed that Modi would recreate the American dream in India. They may not have been prescient about his economics and managerial style but they sensed early that Modi was a global phenomenon, someone who catered to the same parochialism and arrogance of the club of Trump, Putin and Abe. The recent celebration at Houston captured the mutual ecstasy of appreciation.

If success reveals one aspect of the NRI, the past reveals another set of symptoms. The past is one country that the NRI loves. But the past of the NRI is a peculiar country. It reminds one of a comment the great philosopher, Charles M. Schulz, once made his characters recite. Charlie Brown once proclaimed, ‘I love humanity, it is people I don’t like.’ Similarly, the NRI loves India, it is Indians he finds obtuse and intolerable. The NRI loves a certain kind of civilizational India, an India preserved in the formaldehyde of the past. Oddly he sees it as alive and social sustaining. I have heard discussions in Montreal and Ottawa, from GE engineers, discussing the battle of Haldighati. Like Modi they would like to reverse history, create an alternative narrative, a virtual history, where Rana Pratap rides into a triumphant future.

To be fair to the NRI, one must not read him as a univocal presence but as a polyphonic style. The NRI is a happy composite of the Gujarati in Rutgers, the Silicon Valley technocrat, many from our IITs, the NRI academic who has internalized the rituals of the American university, who has mastered its academic table manners if not its intellectual ideals, the Sikh in Canada creating bits of Chandigarh at Montreal and Ottawa. The political emergence of the NRI is twofold. He is an influence on the regime here as he struggles to make his presence felt abroad. He is becoming a force in the US, the UK and Canada. Indians watch the fortunes and future of Sikhs in the Trudeau cabinet or Kamala Harris or Tulsi Gabbard in the US sometimes with more curiosity than we have in our Congress Party.

It is time to acknowledge the political power of memory and nostalgia in today’s world. Today, the tribe and the peasant might be forced into obsolescence, but the past is being reinvented, revived as a commodity and as a placebo. The NRI returning to the Music Academy at Chennai to partake of a culture of music and food represents that. It reflects not just a schizophrenia between his idea of India and the West where he resides but a split-level sense of culture where he is indifferent to the fate of the tribe but ecstatic about his idea of civilization. As a consumer of civilizations, he becomes a threat to culture and a mechanical proponent of development models which are officially hegemonic. One admits there are differences, especially in the new worlds of Australia, New Zealand where they are emerging, but one desperately needs psychoanalysis of his categories to assess the violence and the creativity they embody and unleash.

The author is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations