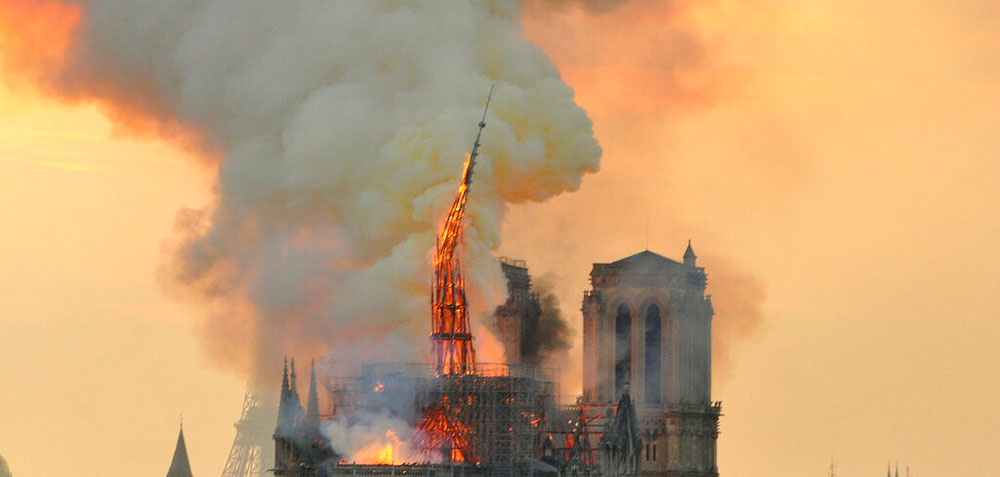

Would there have been the same outpouring of emotion in France if last Monday’s flames had devastated the Eiffel Tower and not Notre-Dame cathedral? Gustave Eiffel’s symbol of the art of modern engineering, celebrating a century of science and industry, inspires awe and wonder. But the tactician in Narendra Modi must at once have calculated the dividend from Emmanuel Macron’s stirring elegy, “Notre-Dame is our history, our literature, our imagination, the place where we have lived all our great moments… the epicentre of our lives.” Modi might have been similarly passionate about the Ganga but never the Taj Mahal.

The conflagration served much the same purpose for Macron as the Pulwama massacre did for Modi. Numbed by shock and grief, a bitterly divided France came together for a time to sing hymns and pray in the shadow of the ruined church. The rise of religion is a worldwide phenomenon. Currently also in the throes of a multi-level election, Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, himself a moderate, is probably congratulating himself on picking a winner in the 75-year-old Islamic cleric, Ma’ruf Amin, as his running mate. Few lay politicians can rival Amin’s appeal in the world’s biggest Islamic nation. But Indonesia isn’t an Islamic republic. Like India, it boasts minorities and a pluralist Constitution. France has been even more determinedly secular since 1789. The ban on turbans, hijabs, large crucifixes and kippahs or yarmulkes (Jewish skullcap) confirms the principle of laïcité, guaranteeing freedom of religion but not recognizing any official faith even though the population is mainly Roman Catholic. Among European countries, France’s religious restrictions are second only to Russia’s.

We know, of course, that what the law says and what people do, often with official connivance, are very different things. In the last days of the Soviet Union, I was twice ticked off by worshippers in Orthodox churches into which I had ventured to gaze upon crowned and gorgeously robed prelates and watch the incense-swinging during elaborate services of which I didn’t follow a word. Once my jacket was unbuttoned. Once my hands were clasped behind my back instead of hanging by my side. Trivial in themselves, both breached ecclesiastical protocol that had lovingly been preserved through all those decades when the gospel according to Marx decreed that religion was the opium of the people and ritual was “the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions”. Like supposedly atheist Soviet communists, the supposedly irreligious French returned in a time of crisis to the comfort of pre-revolutionary roots. Macron, a self-professed agnostic raised in a non-religious family but baptised a Roman Catholic at his own request when he was 12, reached out to believers. “Tonight, my thoughts obviously go out to the Catholics, in France and all over the world, especially in this Holy Week,” he said, referring to Easter.

If the Notre-Dame fire was Pulwama, the massive restoration effort is Balakot. But Macron won only a reprieve. The grieving crowds will not flock to hear Mass. Young male congregations won’t fill up empty church pews. African priests will still have to go from church to church on Sundays. The Yellow Vests are already returning to their truculence, outraged by handsome tax concessions for donations to restore the cathedral. “There is growing anger on social media over the inertia of big corporations over social misery while they are showing themselves capable of mobilising a crazy amount of cash overnight for Notre Dame,” fumed a leader. An undercurrent of Islamophobia is laced with rumours of terrorism and conspiracy in some sections of the social media.

France, too, knows agonized debates about religion, identity, secularism and Islam. But not the crude phenomena of lynching, gau rakshak vigilantism, ghar wapsi and love jihad which are the sangh parivar’s ugly contribution to politics. Far from disgracing anyone in the public eye, the Election Commission’s occasional light slap on the wrist for offenders probably turns them into heroes. Had Bal Thackeray been with us today, he might have acknowledged that his witticism about Indians not casting their vote but voting their caste is complicated by the primacy of religion. That alone need not be condemned out of hand. As the Iranian-American scholar, Reza Aslan, put it, “Religion doesn’t make people bigots. People are bigots and they use religion to justify their ideology.” They can use something else — colour or language — but religion is the Indian’s first identifying mark. It is the Bharatiya Janata Party’s most important card apart from the Leader himself.

India is not yet on the verge of another witch-hunt like France’s Dreyfus scandal. But the impression is forcefully conveyed that underlying the manifold virtues and abilities of which Modi boasts at the drop of a skullcap is his most important strength — the unmatched ability to defend a victimized Bajrangbali from the machinations of a scheming Ali who is also often a terrorist. Pulwama and Balakot fit neatly into this hypothesis. So does the demand for a temple at Ayodhya to honour Bajrangbali’s boss. Many gloat that Adityanath completely upstaged the Election Commission by visiting the Ram Lalla temple while he was banned from campaigning, because the event beamed a more powerful message than any speech could have done. By that same logic, Pragya Singh Thakur’s resplendent presence in shining saffron and prayer beads stresses that the medium is the message. A barefoot, bare-bodied Rahul Gandhi in dhoti and chaddar propitiating the souls of his ancestors was quick to learn that lesson. One wonders whether his mleccha maternal grandfather or Brahmin paternal great-grandfather would have been more surprised.

It’s fashionable nowadays to say Jawaharlal Nehru had no understanding of his country. His reported claim to be the last Englishman to rule India is quoted against him. That is the folly of critics. Kipling’s “What do they know of England who only England know?” can be adapted to these frogs in a well with no awareness of the great world beyond its walls. It was precisely because of his familiarity with both India and the world and awareness of the reasons for India’s backwardness that Nehru was such an unsparing critic of religious ritual and ardent advocate of a scientific temperament. That he failed in his dream of creating a new India blending the science of the West with the spirituality (which, too, he emphasized) of the East is another matter. Friendly critics like the eminent British journalist, James Cameron, and Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew blamed him for not recreating India in his own enlightened image. Unlike sangh parivar bigots they understood the depth and dimensions of the image and weren’t misled by its surface.

All the forces of darkness Nehru hoped to keep at bay have gathered strength since his passing. The current election would not otherwise have been so obsessed with the bogey of Pakistan and tactics involving caste and community to the exclusion of constructive issues. Nor would the tone have been so brash. Personalized advertisements reiterate the Leader’s crucial role; promises pander to the most primitive instincts. The Assamese fear that once the four million people in Assam who were excluded from the National Register of Citizens (the majority being Bengali Hindus) are absorbed, some 14 million Bangladeshi Hindus will be encouraged to follow them. The citizenship (amendment) bill’s present wording wouldn’t allow that but opportunities and compulsions can always be contrived.

Neither the Notre-Dame fire nor the Pulwama attack was expected. But initially at least the response to both was richly rewarding. The yield is already dwindling in France. India’s elections will probably stretch out the jadoo until another miracle (in the Shavian sense of “an event which creates faith”) again mesmerizes the credulous public.