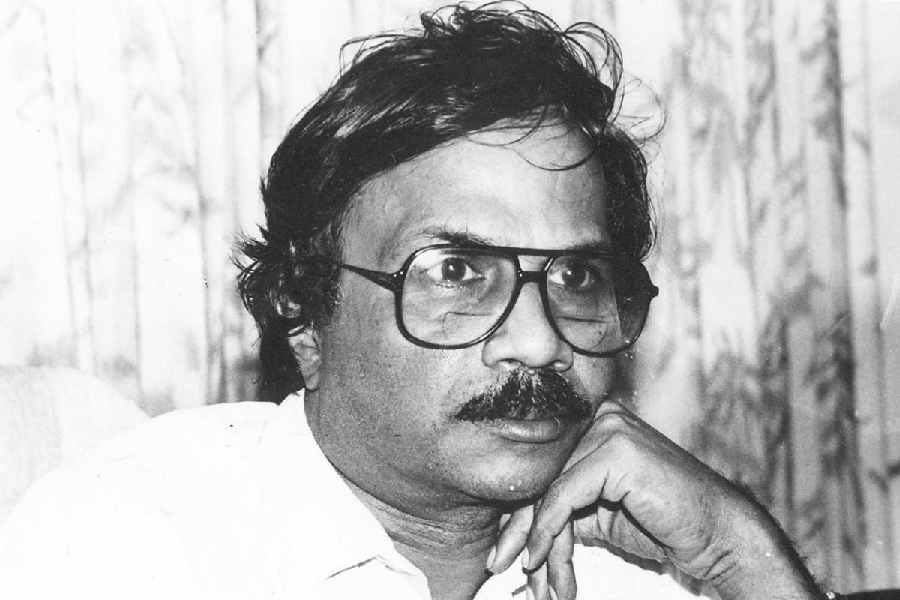

Madath Thekkepaattu Vasudevan Nair (1933-2024), Vasu to his friends and MT to all, who passed away on this Christmas night was the Midas of Malayalam. At 20, his short story won a prestigious prize instituted jointly by the New York Herald Tribune and two Indian newspapers. By 25, his first significant novel, Naalukettu (1958), earned him the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award, the state’s highest literary honour. His cinematic journey debuted with Murappennu (1965), which was based on his story and screenplay and won a National Film Award. Nirmalyam (1973), MT’s first directorial venture, was adjudged the Best Film of the Year at the annual National Film Awards.

MT won seven National Film Awards, including a record four times for Best Screenplay, and 21 Kerala State Film Awards. His Jnanpith came in 1995, and the Padma Bhushan a decade later. A legend in his lifetime, MT was perhaps Malayalam’s most translated writer.

Be it literature, cinema, journalism, or institution building, everything he touched turned to gold. Critical acclaim and commercial success seemed his for the taking. Publishers competed for his works; writers longed to publish in the Mathrubhumi weekly that he edited; producers and directors queued up for his screenplays; superstars vied for roles in his films; and political leaders yearned to associate themselves with him. No other writer from Kerala’s rich literary tradition has cast such an enduring spell on so many generations across every divide. His village, Kudallur, its hillock, Thannikunnu, its river, Nila, the Kodikkunnath temple, and the ways and words of his characters are etched in the Malayali collective consciousness.

In a prolific career spanning over seven decades, MT’s pen gave life to nine novels, hundreds of short stories, and 54 screenplays; he also directed seven films. His oeuvre, marked by versatility, remained deeply rooted in the Malayali social milieu and identity. While chronicling the sweeping changes in Malayali life over the last century, his works delved deeply into the struggles and inner turmoil of individuals caught on the cusp of these transformative shifts.

Manorathangal, an anthology television series featuring MT’s nine iconic short stories, was streamed last August on ZEE5, commemorating his 90th birthday. The series, curated by MT’s daughter, Aswathy Nair, a classical dancer, and presented by the actor, Kamal Haasan, had an ensemble cast including Mammootty, Mohanlal and Fahad Faazil.

MT often attributed his sensibility, values, and worldview to a lonely childhood marked by deprivation — of means, happiness and even health. Borrowed books were his sole solace, shaping his perspective and inspiring his storytelling. Many of MT’s protagonists are young men who struggle and rebel against the oppressive Nair joint family system in varied ways.

Some years ago, MT sprang a surprise with his short story, Sherlock, which transcended his familiar time, space and realistic style. A contemporary masterpiece, it explored the themes of identity crisis and urban alienation through remarkable craftsmanship. A voracious reader since childhood, MT was always abreast of the latest in world literature and cinema. He is credited with introducing Gabriel García Márquez to Malayali readers much before the Latin American author won the Nobel Prize. Yet MT’s repertoire was mainly inhabited by his village and its ordinary folk, including orphans and outcasts. “More than the great oceans hiding unknown wonders, I love my known Nila,” he once wrote.

Nirmalyam emerged as a cornerstone of the Malayalam New Wave cinema of the 1970s, alongside Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Swayamvaram and Aravindan’s Uttarayanam. While many films based on MT’s scripts straddled the line between art and commerce, Nirmalyam stood as a testament to his commitment to pure and socially conscious art. The film poignantly unravels the personal struggles of a young temple priest, serving as a stark exploration of the crippling poverty and widespread unemployment that plagued post-Independence India. It lays bare the disintegration of long-held values and ideals under socio-economic hardships, delivering a searing commentary on the nation’s fractured moral fabric.

Most of MT’s extensive creative output, whether in fiction or cinema, revolves around a recurring male protagonist — an Outsider often misjudged and disparaged by society, including his own people, or betrayed by the woman he loved deeply. This character frequently reflects MT’s background: an upper-caste (Nair) male, impoverished and traumatised by the collapse of the feudal and matriarchal order. This archetypal figure, central to his oeuvre, extends beyond his realistic fiction — Naalukettu (The Legacy, 1958), Asuravithu (Demon Seed, 1962), Kaalam (Time, 1969) — to his retellings of epics like the Mahabharata — Randamoozham (Second Turn, 1984) and the folk ballads (Oru Vadakkan Veeragatha, 1989). Critics have interpreted this trope in various ways. To some, it was a nostalgic lament for a bygone world, flawed yet familiar. Some others found in MT’s works a patriarchal, self-pity-driven fear of women asserting their autonomy. His lyrically exquisite Manju (Mist, 1964) is his only female-centric novel and the first set outside Kerala in the snow-capped Nainital.

Despite his cult status, MT remained solitary and reserved, mirroring the traits of his protagonists — a demeanour he attributed to his troubled childhood. Beyond his close circle, he rarely smiled and was often challenging to engage in conversation. In Kerala, where politics and culture frequently intertwine and cultural leaders openly align with ideological camps, MT stood apart, maintaining a deliberate distance from political polemics. He avoided signing memorandums or public declarations on political or social causes, a choice that often drew criticism for what some perceived as fence-sitting or reluctance to challenge the powerful. MT, however, brushed off such critique, famously asserting, “I value my freedom more than aligning with any camps.”

While he stayed aloof from partisan politics, MT did not always shy away from addressing pressing issues. He spoke out against growing religious intolerance, challenges to secularism, environmental degradation, authoritarianism, and policies like demonetisation. The iconic final scene in Nirmalyam, where a temple oracle, devastated by his tragedies, spits at the idol of the goddess he once worshipped, has been widely debated. MT often remarked that creating such a powerful and provocative scene would be nearly impossible in today’s climate of intolerance.

His final political statement came last January at a public meeting attended by the chief minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, where he hinted at the growing intolerance from the Left too and lamented the extinction of visionary leaders like the late communist stalwart, E.M.S. Namboodiripad. His few but firm words left a lasting impact, as is evident even after his death. Despite the overwhelming outpouring of grief that followed his passing, a handful of Hindu and Islamic fundamentalists did not hesitate to tarnish his legacy.

MT rejected simplistic binaries about art’s purpose — whether it should serve societal progress or exist for its own sake. Instead, his works reflected a deep-seated concern for dignity, diversity, and democracy. In an interview with this writer, after he won the Jnanpith, the maestro said, “I am conscious of the problems of our times. Through my writings, I put questions to society, to our times, to God and myself.” When pressed about his political stance, he succinctly replied, “I am a humanist,” underscoring his enduring commitment to universal values over fleeting ideologies.

M.G. Radhakrishnan, a journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram, has worked with various print and electronic media organisations