Does acquiring knowledge destroy our sense of wonder? The rhetorical question is both polemical and accusatory in hinting at the reality of imaginative deprivation if knowledge, justified true belief to borrow Plato’s epistemological proposition, throws its weight around with a heady hauteur. The question also draws attention to the centrality of wonder that loses its splendour in the humdrum of the human condition. One is reminded of the British author, C.S. Lewis, who, in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, mentions the story of two lives: “the almost purely imaginative and the almost purely rational.” If the former is about the realm of wonder, the latter appeals to the rhetoric of logos in seeking rational knowledge.

The commonplace also feeds into our sense of wonder. What makes the unassuming, old woman selling tomatoes evoke a sense of wonder in the poem, “Tamatar bechnewali buriya”, by Kedarnath Singh? Where does the sense of wonder emanate from? It emerges from the encompassing sense of living kindness the old lady exudes. What is wondrous in her act of sheltering a “brown tomato”, symbolic of a spoilt child, is the act of generosity that nurtures a healing space for care and inclusion. It is the unparalleled depths of motherly love, too deep to plumb into, that radiates wonder.

Unlike a common reader, a critical reader with a discerning eye for wonder will unearth the enchantment that, at times, is too subtle to fathom. The wonder might also spring from an early sense of discontentment that gets dissolved later on as the layers of fascination get unravelled. In this context, Erich Heller’s observation is relevant.

He contends that the study of literature is “purification”, or, he loves to call it, “perception crystallised into conviction and learning into a sense of value”. The culmination of this awe-inspiring trajectory of wonder recalls Tridib, “a man without a country” in Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines, who blazes a trail of identities with the unknown.

How is a sense of wonder fostered by the deft use of intertextuality? One is reminded of Bharati Mukherjee’s self-reflexive novel, Jasmine, that interweaves elements of all three literary works — Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, and G.B. Shaw’s Pygmalion — into a work of immigrant romance. I argue that the sense of wonder also stirs up an unflinching sense of revolt to assert what is distinctly novel and path-breaking. It calls to mind Mukherjee’s well-crafted essay, “Immigrant Writing: Give Us Your Maximalists!” in The New York Times Book Review. Her transitioning to a new mode of expression to radicalise American fiction, which she felt “lost the power to transform the world’s imagination”, is inspiringly strewn with wonder. She sets out to write the untold stories of the Asian immigrants and foreground the ‘Other’, not the post-colonial ‘Other’ but the ‘Other’ of the Western world.

When we talk of intertextuality, can consilience be far behind? The intersection or convergence between disciplines and beyond generates a world of wonder. When disciplinary knowledge outsteps its bounds, it leaves behind a lot of mystifying wonder churned up in its wake. Think of science and one is reminded of Richard Dawkins’s nirvanic vision. Think of art and one is reminded of Virginia Woolf’s metaphor in “A Room of One’s Own”: “Fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners.”

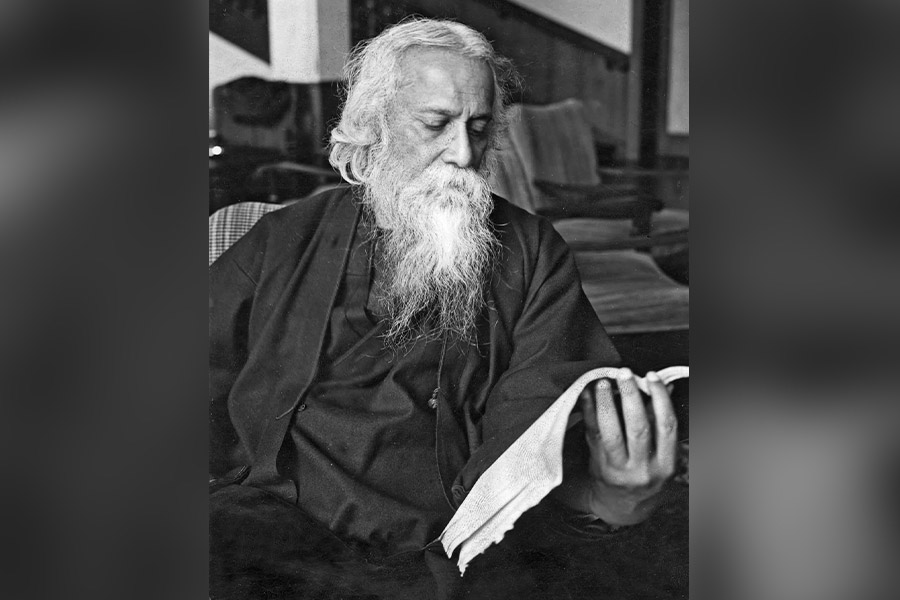

Wonder is also triggered by intangibility. Tagore’s poetry, where the poet draws on the baul concept like “the unfamiliar bird”, connotes an aesthetics of wonder

that calls for a refined sense of intuition as meanings are enveloped in a sense of mystical haze and necessitate a spiritual discovery. For a spiritual aspirant

like the poet-philosopher, Dilip Kumar Roy, wonder is a culmination of deepening wisdom where aspirants “merge into that immobile Silence”.

Wonder leaves its residue unexplained. We are a free-roving wanderer of wonder, aren’t we?

Sudeep Ghosh teaches at The Aga Khan Academy Hyderabad