Among the contrasts between India and Pakistan is how the countries view the Man considered to be the Father of their Nation. Gandhi is savagely dumped on by all sorts of Indians; by Naxalites who consider him a pussy-footed reactionary; by Hindutvawadis who feel that he was too soft on Muslims; by Ambedkarites who feel he was insincere in his opposition to caste discrimination; by feminists who feel he was lukewarm in his opposition to gender discrimination; by modernists who feel he romanticised the past; by traditionalists who feel he disrespected the scriptures.

In India, it is open season on the so-called Father of our Nation. In Pakistan, on the other hand, it is just not done to say critical things about the Father of their Nation. Shortly after Pakistan came into being, a Lahore poet wrote this about Jinnah: 'Your breath alone is sufficient for the nation, oh Quaid-i-Azam/ You alone have been the binding force for the nation, oh Quaid-i-Azam.' Such worshipful adoration has attended Jinnah in Pakistan ever since. If at all there is any complaint, it is that he left his compatriots too soon.

Jinnah died 70 years ago this week. Ever since, Pakistanis have lamented his early demise; had he only lived another five or 10 years, they believe, their land would never have been disfigured by corruption or poverty or terrorism or fundamentalism or military dictatorship. Regardless of party political affiliation, Pakistanis remain convinced that had Jinnah been granted a longer life, theirs would have been a peaceful and prosperous republic, the envy not just of India but of Iran, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia as well. Thus, as an editorial in the Dawn newspaper put it only last week, 'Jinnah's Pakistan is tolerant, progressive, inclusive and democratic. Will Pakistan's leadership return to the vision of the founding father?'

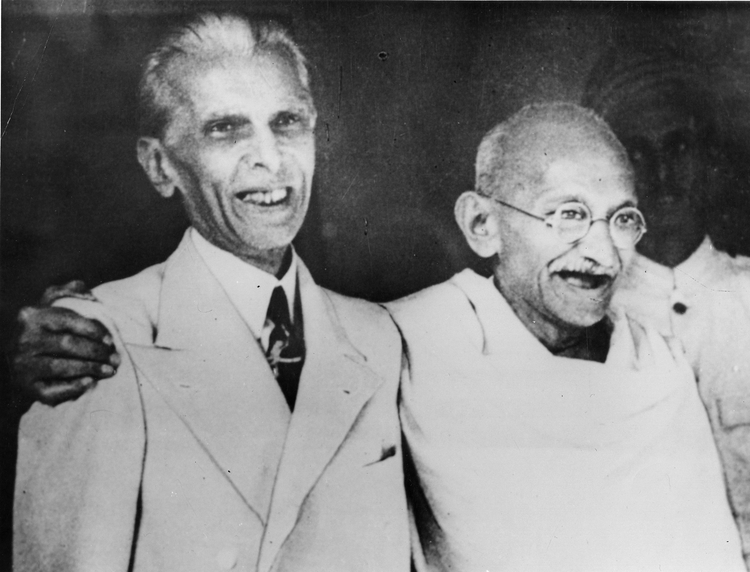

It is not for me, as an Indian, to instruct Pakistanis today on how they must view the Father of their Nation. But, as a historian, I am obliged to remind them - and us - as to how he was perceived by some of his contemporaries, in his own lifetime. I am leaving out of consideration his major political opponents, such as Gandhi and Nehru, whose views on him are all too well known.

Let me begin with a celebrated alumnus of the Aligarh Muslim University, Maulana Shaukat Ali. He was one of the Ali Brothers, who stood with Gandhi (and against Jinnah) during the non-cooperation movement of the early 1920s. In 1926, after this movement had entirely subsided, Jinnah announced his candidature from Bombay for the legislative assembly. Shaukat Ali now issued an appeal outlining the 'reasons why I consider Mr Jinnah unfit to represent the Muslims of Bombay'. These reasons included:

1. 'Mr Jinnah knows nothing about the Muslims of Bombay and what is more he does not care to know.'

2. The Muslims were backward educationally, but Jinnah did not share their sorrows, and thus 'they do not know how and where to approach him in their needs'.

3. Jinnah had stood apart from all Muslim campaigns. He had been opposed to the Khilafat and non-cooperation movements.

4. Jinnah 'has practically become the permanent President of the Muslim League with its very narrow and antiquated constitution. He has killed it. It [the League] sleeps soundly for 363 days in the year and works for two days for Mr Jinnah to have a safe platform to air his views'.

5. 'He cannot brook discipline and cannot work under party organisation where he will have to deal with his equals or superiors.'

Shaukat Ali ended by saying that Jinnah's 'ignorance of Islam is appalling and he cannot be trusted to represent the unfortunate Muslims of Bombay. Even a lamp post would be less harmful ...'

Jinnah won the election regardless. In later years, his star rose steadily, while that of Shaukat Ali declined. By the time of the latter's death in 1938, Jinnah was the unchallenged leader of the Indian Muslims. When, in March 1940, he presided over the annual conference of the Muslim League in Lahore, an admirer from Bombay wrote: 'This was the time when Jinnah, perhaps, gauged his strength for the first time. This was the time when he realized how much devotion he had earned from his followers by sheer service. This was the time when he felt how much confidence Musalmans of India had already reposed in him.'

At this meeting the League passed the so-called 'Pakistan Resolution', demanding a separate homeland for the Indian Muslims. In a note to the Punjab governor, a senior Indian Civil Services officer, Penderel Moon, remarked that the Lahore meeting showed three things: '(a) The importance of the League as the real representative Muslim organisation has been immensely enhanced; (b) Jinnah's own personal prestige has greatly risen. His position as the one all-India Muslim leader is now unchallenged; (c) Muslim opinion is now, outwardly at least, unanimous in favour of the partition of India. Only a very courageous Muslim leader would now come forward openly to oppose or even criticise it.'

Three months after the 'Pakistan Resolution' was passed, the Liberal leader, V.S. Srinivasa Sastri, wrote to Gandhi. 'Nobody can gauge the precise extent of Jinnah's influence,' remarked Sastri: 'As a man [and] as a politician, he has developed unexpectedly. It is no violence to truth to describe him today as a monster of personal arrogance and political charlatanry. Nevertheless Congress is unable to ignore or neglect him; how can the British Government do so?'

Sastri saw clearly that, for the British, 'Muslim displeasure is [now] a greater minus than Congress adhesion is a plus'. So he told Gandhi that 'it profits little now to blame the Hindu-Muslim tension on Britain... We can't abolish Jinnah, any more, than we can abolish Britons.'

On the other hand, Gandhi's own secretary, Mahadev Desai, thought that 'the principal authors of the two nations theory were the Empire builders of Britain', who had emphasized the divisions between Hindus and Muslims and worked to cast them in stone. 'We cannot,' remarked Mahadev, 'fix the guilt either of the monstrosity or the originality of the suggestion on Jinnah Saheb. It was conceived and defined by the 'rulers'.'

The creation of Pakistan was not inevitable in 1940. However, through the Second World War, the influence of the Muslim League and of Jinnah grew steadily. After the war ended, elections were held in British India; and with the League sweeping the Muslim seats, the dream of an independent Pakistan gathered strength. In December 1946, the ICS officer, Malcolm Darling, spoke to the Sardar of Kot, a prominent Muslim notable in the Punjab. The Sardar, noted Darling, 'thought Jinnah would very much like to be the leader of an independent State; he thought him vain and too sure of himself to wish to hear what anybody else had to say; but, on the other hand, he was loyal to those who had always stuck by him... He also mentioned the fact that Jinnah could not be bought... As for Jinnah's cry of Islam in danger, the S[irdar] remarked simply that until his policy had run on these lines he had not known the A. B. C. of the Mohammedan religion.'

That is pretty much what Shaukat Ali had said, back in 1926. And yet, in one of history's most astonishing ironies, it was a man 'who knows nothing about the Muslims and what is more does not care to know' who carved an independent Muslim state out of British India.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in