An editor recently discovered that his head had, in a manner of speaking, been placed on the block, that too on a popular social media platform. An irate reader, taking grave exception at the editor’s decision to publish a piece by a noted historian, had, after pouring vitriol on the article in a rather long post, ended his digital inquisition by raising questions about the editor’s professional competency. This kind of criticism — among the diverse ways in which editors’ heads are set rolling by their critics on a daily basis — must count among the mildest of censures. After all, the sharpening of the talons of hate and the curated demonisation of the media around the world have resulted in vicious trolling being a part of the modern journalistic existence. Not all journalists, it must be pointed out, suffer equally. Two years ago, the Editors’ Guild, a conscientious but benign entity, had been compelled to call out the trolling and the organised harassment of women journalists by demanding a probe into this dark art by the Supreme Court. Journalists — men and women — critical of India’s ruling regime have also faced a disproportionate share of this kind of personal attacks and toxic propaganda.

But what made the said editor’s barracking ironic was the fact that his head had been demanded during a month — September — that urges one and all to ‘be kind to editors-writers’.

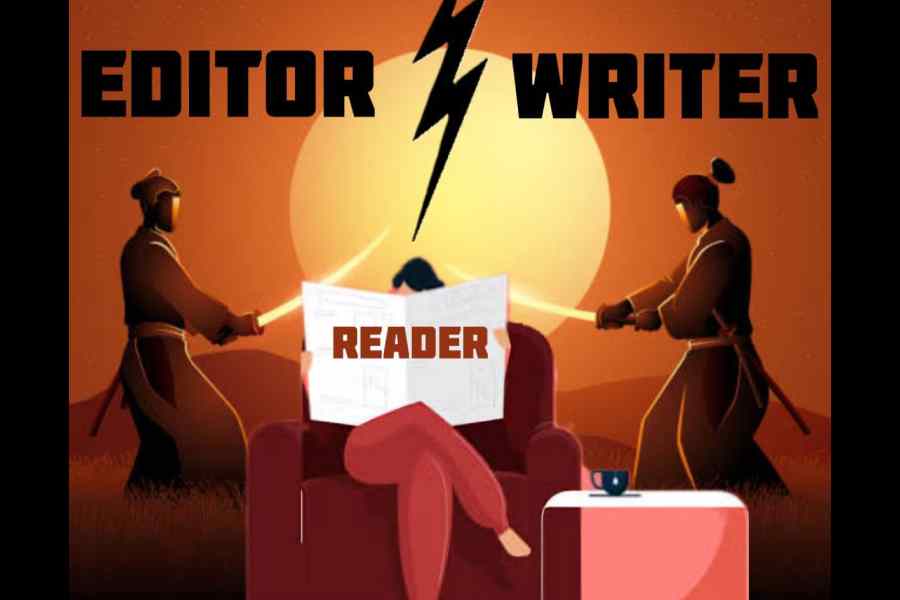

The hyphenation — this columnist’s handiwork — is important. This is because editors and writers, even though they belong to a myriad universes of publishing and publications, often loathe merging their identities notwithstanding several notable exceptions, one of which, Karl Ove Knausgaard wrote in The Paris Review, was the editing job carried out by Ezra Pound “not in any formal capacity, but as a friend, his ruthless hand paring down an early version of T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ into the form in which we know it today.” Several other editors and writers have, in the course of their careers, worked in both capacities. Yet, the hyphen cannot be ignored. This is because it continues to act as a proverbial border between the two distinct worlds inhabited by editors and writers. The border is a necessity too: because the two tribes — those of editors and writers — are, more often than not, at each other’s throats, subtly or otherwise.

M.K. Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj, a slim treatise that the Mahatma wrote in 1909 onboard the SS Kildonan Castle, is an example of the former. The text unfolds in the form of a dialogue in which the Editor, the protagonist, demonstrates a discernible intellectual supremacy over the Reader. The Editor would have certainly held the Writer in disdain too, if only Gandhi had inserted such a character in his text.

The Writer had his revenge in the form of a superb, humorous, guest-of-honour speech delivered by the American author, George R.R. Martin, 70 years after Gandhi had put the Editor on a pedestal. The following is a telling excerpt: “… Left to their own devices, writers talk about only three things… They talk about money, they talk about sex, and they talk about editors.

“Money and sex are things that most writers want and never get enough of. Editors are things that most writers don’t want and get all too much of…

“… If there were no editors in the world, writers would be very happy. They would frolic and play, and publish every word they wrote and they would have lots of money and lots of sex, since they would be very famous and very charming having never experienced rejection. Their egos would fill up the world, their books would be everywhere, and they would mate furiously and produce lots of little writers, who would no doubt write lots of little books. This would never do. It would unbalance the ecology. So editors were put into the world to keep down the writer population… Editors crush fledgling writers… with heavy rejection slips, and they clip the wings of more experienced writers and tell them in which direction to fly — usually the wrong direction — and generally bruise their egos often enough so writers grow bitter and disillusioned and turn to drink… If it weren’t for editors, writers would never drink…”

The journalist, Joshi Herrmann, once pointed out that in a profession — journalism — filled with “borderline alcoholics”, Harold Evans, that legendary newspaper editor, did not drink. How Evans remained a teetotaller would remain a mystery to editors, especially those in newspapers, who would swear that — paraphrasing Martin — if it weren’t for some writers, with their grammatically-shoddy drafts, their monumental egos, and their indifference to deadlines, among other frailties, an editor would never take to the bottle.

To this accusation from the clan of editors, the Writers’ Union may well respond by pointing to the mound of harsh rejection slips or to manuscripts that have been bent out of shape and rest their case. Little wonder then that H.G. Wells is believed to have muttered “No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else’s draft.” Christopher Hitchens also chimed in — unhelpfully for editors — to say, “Authors who moan with praise for their editors always seem to reek slightly of the Stockholm syndrome.” But Arthur Plotnik, an American editor and librarian, would have none of this. He underlined the indispensability of the editor, albeit theatrically, when he said, “You [the writer] write to communicate to the hearts and minds of others what’s burning inside you, and we edit to let the fire show through the smoke.”

This unceasing, often comical, conflict between the editor and the writer raises an interesting dilemma regarding the idea of ownership of a text — be it a book or an op-ed. As the creator, a writer’s claim on his/her work, logic would suggest, is indisputable. But the editor’s claim of making the writer’s draft shine through rigorous, patient polishing — getting rid of flab, correcting grammar, sharpening prose and so on — cannot be taken lightly either.

So who should the final text belong to? The writer? Or the editor?

Perhaps neither.

This is because amidst their squabbling, both the editor and the writer often forget to acknowledge the third, and most important, person in the room — the reader. No exercise in creativity is complete unless it acquires the seal of approval or, equally, the stamp of derision from the person — the reader — at whom creative endeavour — books, newspaper articles et al — is directed. It is the reader who, given his/her principal claim on creativity meant for public consumption, reveals the irrelevance of the war waged by the editor and the writer.

And if the aggrieved reader — the Boss — demands, rightfully or wrongfully, the head of the editor or that of the writer once in a while, so be it.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in