The Indian economy, like other emerging economies, requires a strong State for supporting the large corporate-driven market economy in particular and maintaining social order in general. The functioning of market economies based on private property creates ever-growing economic inequalities in wealth and income. This does not necessarily mean that absolute poverty increases. Rather, it is the economic distance between the very rich and the very poor that keeps increasing at an astonishing pace. This tendency is an integral part of capitalism, and has been distinctly visible throughout its 200 years of history, barring a very short period. This was from the end of the Great Depression of the 1930s to approximately the early 1970s when the growth of economic inequality slowed down. It was the era of the interventionist welfare State following a particular redistributive strategy that created new jobs and incomes and a new social compact. However, with expanding markets and rapidly evolving technologies, the power of large corporations increased dramatically. At the same time, the power of the nation state to determine its own economic fortunes eroded. That was the decade of the 1980s and 1990s in the 20th century.

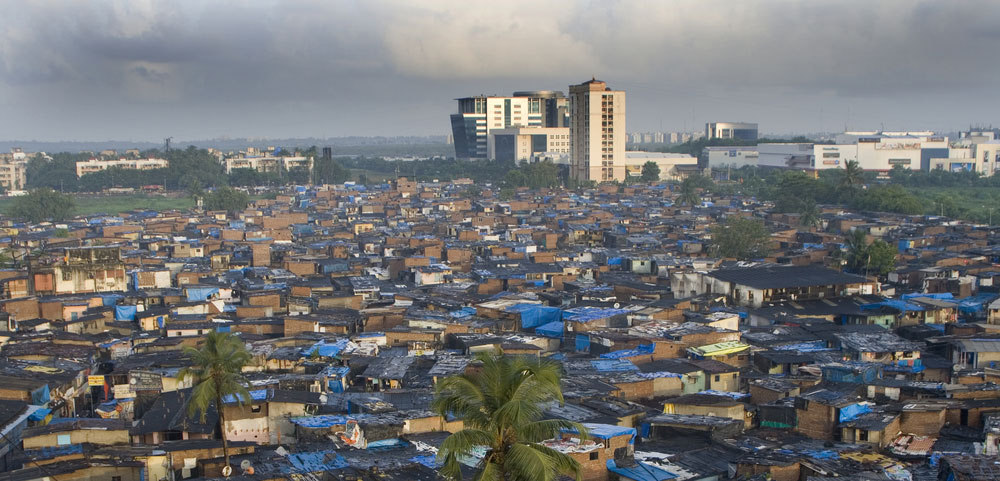

We are now living in a stage of history in which there appears to be a reversal of globalization even in countries like the United States of America. Economic uncertainties have made nations look for powerful leaders and seek isolationist economic policies that aim to keep out enemies and immigrants. The reason is linked to rapid economic growth and its consequences. The world is obsessed with high rates of growth of national income — the amount of goods and services produced. This manic concern with growth creates greater incomes and opportunities for large corporations and for the rich. Consumption grows and the material standard of living of the top 10 per cent in poor countries increasingly resembles the standard of living in the richest countries of the world. In populous countries such as India, the absolute size of the 10 per cent is very large. This class holds enormous influence over society and polity. On the other hand, the distress of the remaining 90 per cent keeps rising and is marked by looming uncertainties, high unemployment, falling farm incomes, social humiliation by the rich upper castes, shrinking opportunities for gaining worthwhile education and the lack of affordable healthcare. The deprived class, especially the very poor, can get frustrated, angry and desperate. It is perhaps the reason why the Naxalite movement has spread far and wide in the poorest districts of India.

Such an economic and social situation is a matter of life and death for the rich as well as for the poor. The rich get worried about social revolutions, or political violence aimed at their obscene opulence. Hence the poor have to be controlled and made to play the game according to the rules set by the rich. On the other side, the very poor, without some hand-holding by the State, would actually starve and perish. If playing by the rules of the rich man’s game allows them to live precariously rather than die, the choice is obvious. This is where the agency of the State lies, not as a regulator of the market and to supplement what the market cannot provide, but as a policeman that controls dissent. Big corporations do not like economic spaces to be captured by the State. They, however, do need a workable social equilibrium. The task of the State is to minimize dissent by building a consensus on the economy or by using coercive violence whenever required. The Indian State has been doing exactly that for the last 50 years. The particular political party at the helm does not matter: it could be the Congress or the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Trinamul Congress or even the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The economic agenda is more or less the same: let private capital thrive and let the poor get budgetary doles, which are usually insultingly inadequate given their depth of deprivation. There are phases when the manufacturing of consent for the system goes on smoothly; there are other times when the coercive nature of State violence becomes overtly visible. During the last five years, India has witnessed a remarkable honing of State control over society compared to any time in the history of independent India. Yet, despite this, the Indian State has very little effective control over the economy.

There are many institutions and strategies available to the State to exercise control and influence. People can be made to accept the order of things out of conviction or out of fear. It depends on who the person is and where he/she belongs in the social hierarchy. One institution that can be the easiest to use is the media. Media houses are usually owned by large businesses and they depend on other businesses for advertisement revenue, which forms the basis of their profitability model. Since 2014, the way the electronic and print media have been used by the State to support the government has been stunning. A well-thought-out and organized approach to social media has helped the BJP gain control of that space too.

The second sphere in which the National Democratic Alliance government has been extremely effective is in being able to exploit religion: linking one’s religious beliefs inextricably with one’s love for the country. A heady mixture of mythology, raw emotions, patriotic grandeur and illusions about the good life led people to believe that a strong State with an uncontested leader was the safest bet against a string of enemies conjured up from within and outside the nation. Religion and nationalism have become potent opiates in the hands of the political class.

The third sphere of influence is in doling out small morsels from the tax revenue kitty to placate the poor with the promise that ‘there is more where the crumbs come from’. The sum of Rs 6,000 to be given to all farmers is a good example. These measures are buttressed by other schemes too, like building toilets or providing electricity poles to villages. These steps create the impression of vikas being delivered to all already, or just about to come in the near future. Intentions are, after all, more true than actual delivery. In the absence of real opportunities or a universal safety net, Indians have stopped demanding anything more than these pathetically low doles received through unbelievably corrupt delivery mechanisms.

The fourth area is the growing control of the State over official economic data. Why should ordinary citizens be concerned at all by these debates on data? There are a number of reasons why we should. In today’s world, data is king. It is the era of big data, and databases are invaluable for commerce as well as to curb dissent. Substantiation with data is vital to clinch any argument. Since facts underlying the numbers cannot be validated on all occasions (like macroeconomic statistics), the credibility of data matters. Finally, data are actually used to inform public policies, which, in turn, have real effects on society and economy. In the post-truth era of fake news, massaged data can create lasting false impressions.

Finally, the last five years have witnessed the use of fear as an instrument of political control. The growing extent of this is unprecedented. The violence has not been widespread but selective: a few cases of lynching, a few murders, a few unexplained arrests, and an ominous silence from the ruling leaders. They are all signals: if one is not supportive of the State, one’s identity is lost — as a citizen, perhaps even as a human being. The State now has an undisputed leader with a landslide mandate from the majority. The nation has succumbed to his agenda of making a New India. The curtain has begun to rise. A basic apprehension remains: are all things new necessarily better, even if the majority thinks so?

The author is former professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta