The past is many things, from being freewheeling nostalgia to becoming an imagined site of humiliation crying out for revenge. Whatever else it is, it certainly is an eloquent crystal ball showing up the present in its true colours. The present has always been an enigma to the human mind, turning ‘Who am I?’ into a complex philosophical question. Be it for an individual, or for a given society, the clues for deciding who one is need to be located in the past. Invariably, the present identity is a gestalt of the lengthening shadows of many bygone spots of time.

As I think of myself and my India during the 2020s, I tend to turn to many pasts that have come together to form the present. Towards that quest, three past decades stand out as having shaped the India of recent times: the 1990s, the 1940s and the 1920s. The 1990s unfolded phenomenal political and economic events, while the 1940s were the years filled with epoch-making historical developments. In comparison, the 1920s were less dramatic, yet profoundly impactful, for India. That decade gave rise to a new sensibility, which shaped the essentials of India’s modernity. Since we are in the 2020s, it is somewhat amusing to turn back and see from a century’s distance what India was doing in the 1920s.

The decade was bracketed between M.K. Gandhi establishing the Gujarat Vidyapith in 1920 and the world-famous Dandi yatra in 1930; between B.R. Ambedkar launching Mooknayak in 1920 and his signing of the Poona Pact in 1932; it was also bracketed between the birth of Vikram Sarabhai in August 1919 and C.V. Raman’s Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930, between the birth of the Kathak dancer, Sitara Devi, in 1920 and the birth of Chandralekha in 1928. As for the most illustrious among India’s spiritual leaders, we see the Ramana ashram of Ramana Maharshi set up in 1922 and Sri Aurobindo’s realisation of a ‘divine consciousness’ in 1926.

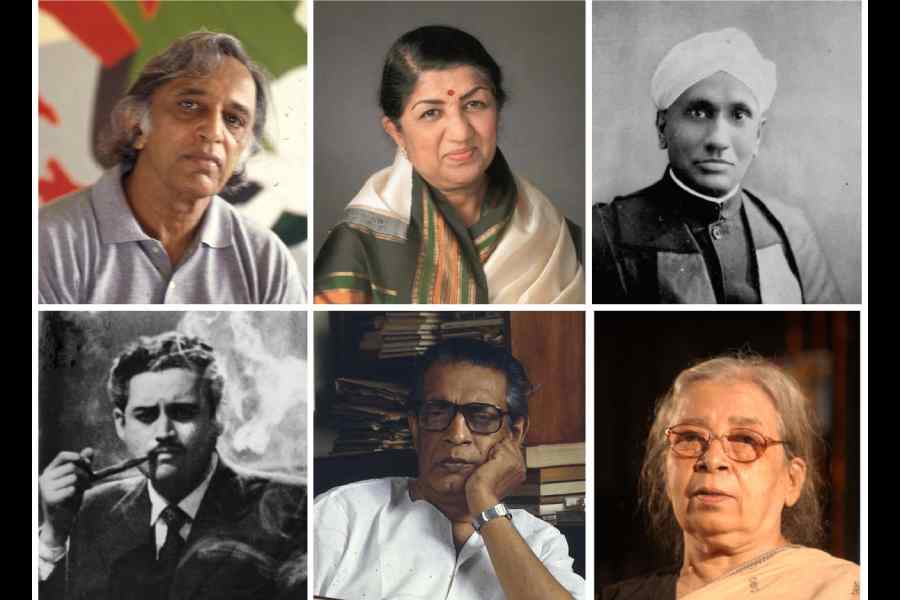

The 1920s were beginning to bring exceptional talent from small-town India to shape the nation’s sensibility. Some of the world-famous and entirely modern painters of India were born in small towns or agrarian cities. F.N. Souza born at Saligao in Goa in 1924; S.H. Raza born at Kakkaiya in 1922; V.S. Gaitonde at Nagpur in 1924 and Tyeb Mehta at Kapadvanj in 1925 are no ordinary names. Their paintings have enthralled art collectors and museum-goers in global cultural centres. Close to my town of residence, Dharwad, is a village called Ron (or Rona). Its current population is less than 25,000. A century ago, it was just a few thousand. The most mesmerising among twentieth-century classical singers, Bhimsen Joshi, was born at Rona in 1922. What India came to recognise as Indian music in the twentieth century received an unmatched contribution from the children of the 1920s.

The all-time-great, Satyajit Ray, was born in 1921, Ritwik Ghatak in 1925 and Guru Dutt in 1925. These children of the 1920s defined not just India’s sensibility but also its image in the world. Pandit Ravi Shankar was born in 1920 as were the playback singers, Hemant Kumar (1920), Talat Mahmood (1924), Lata Mangeshkar (1929) and Kishore Kumar (1929). The golden age of Indian cinema also rested on the shoulders of the children of the 1920s, which saw the birth of Dilip Kumar (1922), Dev Anand (1923) and Raj Kapoor (1924). They contributed to shaping India’s sentiment for most part of the twentieth century.

Perhaps a far more profound impact on twentieth-century Indian modernity was made by the writers born in the 1920s. Among them were, to name just a few, Shrilal Shukla (1925), Mahasweta Devi (1926) and Qurratulain Hyder (1927). It won’t be an overstatement to say that the artistic sensibility and the literary taste of twentieth-century India was shaped by the children of the 1920s.

If so many singers, writers, artists, scientists were in their early childhood in the 1920s, there must have been something in the air which they imbibed and transformed through their creative expression in the later decades. The 1920s was the decade when Mahatma Gandhi was invited to preside over the Congress at its Belgaum session in 1924. Five years later, in 1929, the Congress had adopted the resolution of complete independence at its Lahore session. In the 1920s, India was coming closer to the rest of the world. The First World War had created the context for India’s greater exposure to what was happening outside India. Therefore, Indian social leaders were aware that Benito Mussolini had floated the Blackshirts in Italy and that Adolf Hitler had mobilised the Brownshirts targeting gypsies, Jews and communists in Germany. The more literate among Indians of the 1920s were aware that Albert Einstein had published The Meaning of Relativity in 1922. During the 1920s, Indian literary classes had much less difficulty than before in accessing the works of American and European writers. Thus, just as Rabindranath Tagore’s Raktakarabi was welcomed by Indian audiences with excitement, so were Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) and Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929). W.B. Yeats’s Michael Robartes and the Dancer of 1921, leading to his Nobel Prize in 1923, was perhaps not easily understood by Indian readers of the 1920s. Yet, his connection with India through Mohini Chatterjee and Rabindranath Tagore was known to them. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land appeared in 1922 and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway in 1925. They did not immediately appeal to their Indian contemporaries. Yet, the idea that the world had entered a new age marked by such writers was very much in the air in India. The social sensibility and literary taste of India in the decades till the 1980s continued to be dominated by what had sprung up during the 1920s. Perhaps, it was this sensibility that dominated the Indian mind much beyond Independence and through the times that historians call Nehruvian India. The political and institutional infrastructure of the 1950s was coined by Nehru; but the cultural and the intellectual software was of the 1920s’ mint. Quite ironically, the forces that have militated against that sensibility too have their roots in the 1920s. V.D. Savarkar’s Essentials of Hindutva doctrine was scripted in the 1920s.

A relook at that decade will easily show that we in the 2020s can in no way measure up to our forebears of the 1920s. The 1920s generation opened India up to modern ways of thinking; the India of 2020s is all about clinging to the deadwood of tradition. The present decade, with its epidemics, forest fires, floods, violence against women, Islamophobia, wars, economic disparity and totalitarian States, is no match for the 1920s. The distance of a century between the two appears a lot more than a century.

G.N. Devy is Senior Professor of Eminence and Director, School of Civilisation, Somaiya Vidyavihar University