I am a snoot. An unrepentant, incorrigible snob. I abhor the mediocre.

I am irremediably class-conscious; cannot abide the crass, the coarse, the crude. The vulgar I sicken at.

Of being illiberal, intolerant, I am not only glad; I am proud. I adore that form of conceit.

On being dogmatic about my likes, dogged about my dislikes, I will not yield.

I will make no defence, rather enjoy the fact of my being wholly selective, totally subjective, and shamelessly exclusive in the company I keep. I will admit and embrace those I like, show the door or keep at an emphatic distance those I do not. And care a hoot about how my attitude might strike ‘them’.

I am, let me now hasten to say, talking with brutal honesty of myself, my life, in the world of books.

All I have said is about what I feel about books, not people or places. There is no ahimsa in me when it comes to books of no worth.

This line of intolerant and arrogant thought has been occasioned by a book of books, the purest of gold, I found in my daughter’s bookshelf shortly before I started writing this column. It is about that book that I am now writing.

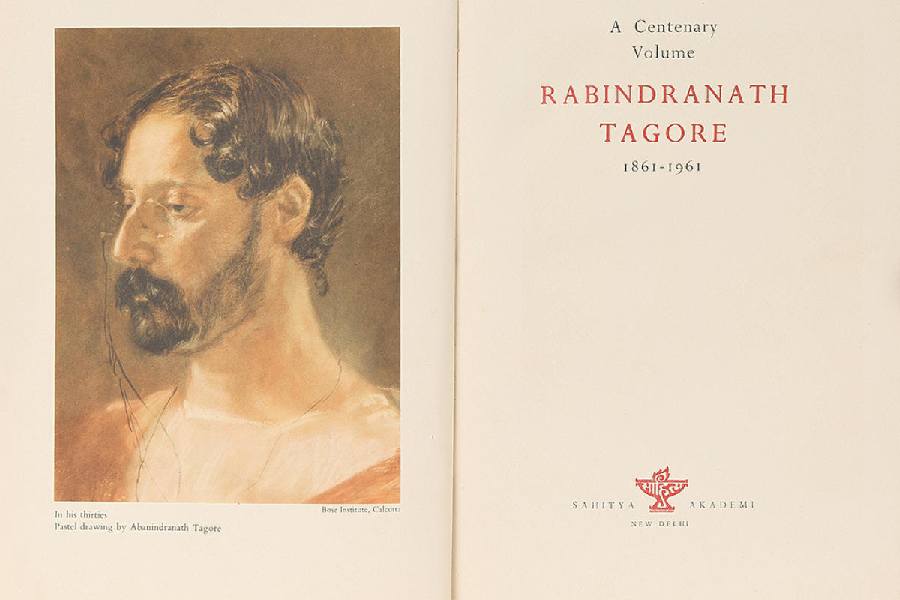

The world celebrated in 1961 the centenary of the birth of Rabindranath Tagore. India’s national academy of letters, the Sahitya Akademi, then just seven years old, brought out the classiest, the choicest, the most beautiful of books to commemorate the great man. Rabindranath Tagore 1861-1961, A Centenary Volume (picture) is the finest volume on the entire oeuvre and the genius of the man Albert Schweitzer, in his tribute, calls “the Goethe of India” and adds “This completely noble and harmonious thinker belongs not only to his people but to humanity.”

The volume has fifty-nine contributions of a calibre that those who know the diamond in its composition (not as a good sold in jewellery shops) would describe as the 4Cs — cut, colour, clarity and carat weight. Of these, thirty are from non-Indians. Of the twenty-nine that are from Indians, nineteen are from Bengal-born, Bengal-raised, Bengal-imbued women and men of formidable eminence.

Plus, I should in sheer delight add, a Chronicle and a Bibliography by four master-craftsmen — all Bengali — Prabhatkumar Mukhopadhyay, the author of the only-one-of-its-kind Rabindra-Jibani, Kshitis Roy, author, translator, curator par excellence and editor non-pareil of the Visva-Bharati Quarterly for many years, Pulinbihari Sen, bibliographer by instinct and training and compiler of the instructive Patrabali, the collection of letters between the two Nobel laureates, Jagadish Chandra Bose and Tagore, and — the youngest among them — Jagadindra Bhaumik, bibliographer of Tagore’s Bengali works as the Rabindragrantha-panji. I have read none of the works mentioned in this paragraph but can tell their value as a sightless man can the fragrance of the Hasnuhana or Raat-ki-rani (Cestrum nocturnum) at night.

The volume opens with an Introduction by Jawaharlal Nehru who, not as prime minister but as an author, was the Akademi’s first president. I am partial to that man’s thoughts and words. But not many readers will disagree with my unreserved admiration of the following in his Introduction: “Gandhi came on the public scene in India like a thunderbolt shaking us all, and like a flash of lightning which illumined our minds and warmed our hearts; Tagore’s influence was not so sudden or so earth-shaking for Indian humanity. And yet, like the coming of the dawn in the mountains, it crept over us and permeated us.”

Pearl Buck, the tender-tough American novelist, says in her piece something I would have expected from a spiritual thinker, not from her pen dipped in the inks of human conflict: “… he spoke to us of mind and soul, leading the human spirit towards God. No narrow God created by man, but the spirit of the universe itself…”

In her piece, the dance-guru, pioneer of handloom weaving and animal welfare, Rukmini Devi Arundale, says of him: “Tagore was extremely sensitive to everything. I think ugliness affected him like poison. He liked beautiful colours; he liked people to dress well. He even found it difficult to talk to people who had harsh voices. He was sensitive to crowds and noise, though he was often in the midst of crowds.” She must have read Tagore’s play, Visarjan, in which he excoriates the practice of goat sacrifice in a Hindu shrine and, we may assume, by automatic extension, also at Eid.

The Argentinian aesthete, Victoria Ocampo, writes in her intensely intimate account of what can only be called a passionate devotion: “… I came little by little to know Tagore and his moods. He partially tamed the young animal, by turns wild and docile, who did not sleep dog-like, on the floor outside his door, simply because it was not done.”

Personal memories, studies and appreciations and a section titled “Tagore in Other Lands” give us more than a portrait of the man. They vivify an age, a renaissance-to-be.

Typically, one contributor has done his work wordlessly. Satyajit has designed the jacket. (He also designed the Sahitya Akademi’s logo). The jacket is the only aspect of the volume in my hands that has suffered the ravages of time. But like the black and white prints of Ray’s films, is the more precious for its wear.

But the most amazing thing about this book is that its editor-compiler, who has to have been an exceptionally gifted and punctilious person, is un-named. A little research will yield it but the book’s pages are silent on the identity of the person who has put this work of pure quality together. A more stunning exercise in deliberate self-elision is hard to imagine. This priceless volume has many contributors, a great publisher (Sahitya Akademi), and has been served staggeringly well by its printer (Saraswaty Press, Calcutta). But the man who conceived its design, choreographed its shape and structure, edited it, and gave it its very life, has stayed anonymous.

Rafiq Zakaria edited A Study of Nehru published in 1959 by The Times of India. Appearing in the year Nehru turned 70, that too is a book of sheer class, with contributions from all over the world and a gallery of photographs as well. Twenty years earlier, in 1939, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan edited a volume of appreciations of Gandhi by world figures published by George Allen & Unwin on the occasion of the Mahatma’s 70th birthday. That volume is a gold standard for such endeavours. There was earnestness in those efforts, there was quality. And no ego.

Among those in high office and now, even more, in the world of commerce and industry, arrogance reigns. And as these worthies turn 60, 70, 80, 90 or pass, their adherents vie with each other for a place among the voluble mourners to lavish tributes on them, each claiming great kinship with the dearly departed, and asking for a slice of the moon to commemorate the late lamented. Money being no problem for them, they produce glittering volumes on their heroes. This sorry practice will continue forever, I am afraid. But for those who have seen the Sahitya Akademi’s Tagore 1861-1961 and the Zakaria and Radhakrishnan volumes on Nehru and Gandhi, respectively, the choice is clear. They will need to be class-conscious, illiberal and dogmatic about what is and what is not worthy of the paper it is printed on.

When it comes to books, being conscious of class, exclusivist, intolerant is essential. And thereby, show the mediocre and the vain-glorious their place — the bin of outright rejection.