Western Uttar Pradesh is witnessing a novel unity between Muslims and Hindu Jat peasants in the course of the agitation against the three farm laws. This is important for an obvious reason. The Muzaffarnagar riots of 2013 which had created a strong communal polarization in this region had enabled the Bharatiya Janata Party to reap rich electoral dividends in the 2014 parliamentary elections. Because of the huge number of seats it won in Uttar Pradesh, it got an absolute majority in Parliament, something that had eluded all previous BJP governments.

The effects of this polarization also contributed to the BJP’s triumph in the UP assembly elections and even in the 2019 parliamentary elections. In fact, the perpetuation of such a communal division has been central to the BJP’s recent electoral ascendancy. The fact that this division is being overcome because of the anti-farm-law agitation helps undermine this ascendancy.

So complete is this break from the past that an influential BJP leader of the region, currently a member of the Union council of ministers, who thought he could defy the

leaders’ call to avoid BJP bigwigs even on social occasions by turning up on such events, was not allowed to remain in the village.

Mass movements on issues of material life have this remarkable effect of uniting people. The anti-colonial struggle itself was a vivid example of this. The fact that a country marked for millennia by the institutionalized inequality of the caste system and by horrendous gender, caste and class oppressions could unite against colonial rule and adopt a Constitution that guaranteed universal adult suffrage, one-person-one-vote, a set of fundamental rights for all citizens and the separation of the State from all religions became possible because of the logic of the anti-colonial struggle and the mass movements it unleashed.

The philosopher, Akeel Bilgrami, provides a very specific example of the effect of a mass movement in inducing attitudinal change. In 1921, a bill for introducing women’s suffrage was brought before the Bengal Provincial Legislative Council and was defeated, mainly because of the opposition of the Muslim members. But as the Khilafat Movement gathered steam, members of the Muslim community participated in large numbers in it. Meanwhile, Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das had started his Swaraj Party within the Congress to fight elections for entering legislatures so that progressive laws could be enacted; many Muslim participants of the Khilafat Movement joined the Swaraj Party. When in 1925, the bill on providing suffrage to women was brought, once again, before the Bengal legislature, it was passed with Swarajist Muslims, many of whom had opposed it in 1921, supporting it despite the Swaraj Party not issuing any whip. Participation in a mass movement, Bilgrami argues, had brought about an attitudinal change in prominent members of the Muslim community because of which they dropped their earlier opposition to women’s suffrage.

The Khilafat Movement, although anti-imperialist in its outlook, was not even a progressive movement, and was certainly not concerned with issues of material life. But it was not a divisive movement. It still had this capacity for bringing about significant progressive changes in people’s attitudes. (In fact, many early communists had emerged from its ranks: the Tashkent School imparting political training to communists had recruited many Khilafatists. Some of them were arrested by the British while returning to India and tried in the Peshawar Conspiracy Case).

Introducing respect for democratic values and unity among people is a hallmark only of non-divisive movements, for which I reserve the term, ‘mass movements’, as they are not directed against a particular segment of the masses themselves but are open to all. Many journalists had described L.K. Advani’s rath yatra for building a Ram temple in place of the Babri masjid as the biggest ‘mass movement’ witnessed in a long time; but this is an indiscriminate use of the term, which obliterates the distinction between movements that unite people and movements that divide people. Movements over issues affecting material life typically unite people: the ongoing kisan struggle, described as the biggest mass movement in the world, is one such.

The Jat-Muslim unity is not the only novel unity being forged. There is an emerging unity between kisans and agricultural labourers which is even more striking because between these two groups there is not only a class contradiction (employers versus employees) but also a caste contradiction (Jats versus Dalits). This is a long-standing contradiction prone to occasional flare-ups, as had happened some decades ago in the village of Kanjhawala on the outskirts of Delhi when CPI-led agricultural workers had come into conflict with Jat landed interests.

To imagine these two groups coming together would have been unthinkable earlier, but the mass movement against monopoly capitalist encroachment on the agricultural sector has united them. There is a common realization that if the farm laws are allowed to become operative, not only would the kisans come under the hegemony of monopoly capital, to the point of being pushed into landlessness, but also the agricultural labourers would find themselves without work as agriculture becomes corporatized. This realization has overcome their centuries-old hostility.

Likewise, the large-scale participation of women in the anti-farm-bill agitation points to yet another major break in traditional patriarchal relations. Women becoming so active in the movement is partly explicable in terms of the years of suffering that have led to widespread farmer suicides, but the scale of their participation is as unprecedented as the scale of this movement itself; the importance of the issues underlying the movement has contributed to both. This is bound to have a lasting impact on gender relations. Similarly, the support extended by industrial workers in the neighbourhood to the agitating kisans has become a striking example of worker-peasant unity that was hitherto rather elusive.

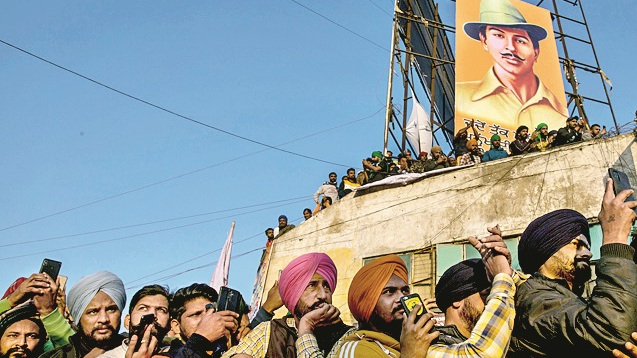

The kisan movement has not just fostered unity among disparate and even conflicting groups; the symbols it has used, the memories it has recalled, the history it has recovered are all highly evocative. For instance, the call for a ‘pagdi sambhal’ day is a celebration of an episode in 1906 when the colonial government had passed three anti-farmer laws, and in opposing these Bhagat Singh’s uncle, Ajit Singh, had played a leading role. Appropriately, Ajit Singh was remembered by the present kisan movement on the ‘pagdi sambhal’ day it observed on February 23. Likewise, the pervasive evocation of Bhagat Singh’s memory that informs the present kisan movement is indicative of its stress on secularism, non-divisiveness, and unity among the people.

Divisive movements by contrast, those that pit one segment of the people against another, typically a majority community against a hapless minority, do not have this trait of bringing about any attitudinal changes in favour of democracy and unity. On the contrary, they build on the existing fault lines in society, on existing suspicions, prejudices and latent hatreds and exacerbate them; their success arises precisely because they build on the existing divisions based on the prevailing consciousness, which are not transcended but reinforced. Because of this, the oppressive society within which this consciousness has been nurtured also gets reinforced instead of being challenged. Such movements reinforce oppression, unlike the kisan movement which seeks to prevent a new chapter of Neel Darpan-style oppression.