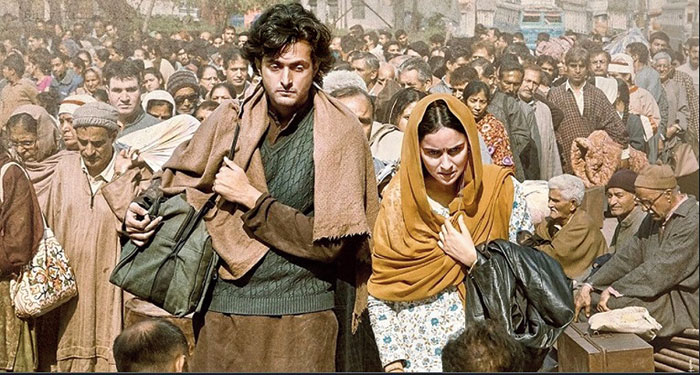

What is it like watching Shikara in Kashmir? It certainly is not the same as watching the film outside the Valley where its subject — the expulsion of Kashmiri Pandits — has strongly resonated with the people.

Shikara is seen as a welcome recognition of the sufferings of Pandits, a cinematic ode to the community’s resilience on the 30th anniversary of its exodus from Kashmir. Criticism, if any, has generally been about the movie not being explicit enough about the atrocities perpetrated on community in the Valley.

But in Kashmir, Shikara has become contentious for its portrayal of the events that led to the exodus. Given the absence of cinema halls and, in recent times, high-speed internet, only some people have been able to watch the film. But the media buzz around the film, which has chosen to portray the Pandit exodus as an organized expulsion by the Valley’s Muslim majority, has offended the local people. What has riled them even more is that Shikara is seen to faithfully reproduce the Pandit account of the exodus, passing over the Muslim side of the story in the process.

Kashmiri Muslims have an alternative narrative, which disputes the Pandit version. Kashmiri Muslims never tire of quoting the official Pandit casualty figure of 209 spanning the period between 1989 and 1994. According to figures quoted by a former minister, Raman Bhalla, in the then state assembly in 2010, no Kashmiri Pandit has lost his/her life since in the ongoing conflict in the region. Similarly, as for the exodus, Kashmiri Muslims object to the accusation of forcing the Pandits out, arguing that the unrest was not a communal rift between the two communities that created the conditions for the exodus.

Both narratives, however, reflect only a part of the truth. They highlight only what is convenient to each. Over the years, the two accounts have become so sacrosanct that one can only challenge them at one’s risk. But it is also important to confront these popular versions. It is true that many Pandits were killed by the militants for being alleged informers of the security agencies, but Muslims, too, were butchered by extremists and in larger numbers. If we go only by the official number of the killings in Kashmir, around 42,000 people have lost their lives in the past 30 years — unofficial estimates allege that the casualty figure is twice this number — among whom 14,038 were civilians, almost all of them Muslims. They died in cross-fire, grenade attacks, massacres and custody killings while a significant number were killed by militants. It is also true that the loudspeakers crackled with provocative slogans through the nights as has been shown in the film. These slogans were part of the protest and they are still heard today.

From the outbreak of armed militancy in the middle of 1989 until January 19, 1990 — the day now observed as the exodus anniversary by Pandits — there was not a single instance of a major communal riot in the Valley. In fact, there has rarely been any in the Valley in the decades preceding 1990. The few that have taken place were localized and limited in scale.

But yes, there was every reason for Pandits to be terrified of the evolving situation in the Valley. As the 1990s rung in a new decade, Kashmir was sinking into deeper turmoil with every passing day. More and more youth were taking up arms and protesters were hitting the streets. And the community bore the brunt of the violence directed at those who were seen to be against the secessionist movement. This severely tested efforts by Pandits to negotiate the division. After a point, they gave up the effort and with good reason. The targeted killings of members of the community further accelerated this end-of-the-road feeling. They were dying alongside Muslims as a consequence of the unrest.

It was this dynamic that precipitated the Pandit exodus rather than an organized Muslim campaign against the community as is being projected. That said, the Pandit exodus remains the darkest chapter in Kashmir’s troubled history in the past three decades. The community’s suffering has been enormous. What is more, Pandits are besieged by the prospect of an ethnic extinction.

Tell this to Kashmiri Muslims and they will readily acknowledge the suffering of Pandits but would refuse to be blamed for the community’s expulsion. In some instances, they would accuse the then governor, Jagmohan, of abetting the eviction of Pandits. Kashmiri Muslims will tell you that they are victims of a far bigger — and unfolding — tragedy. Some of them believe that both communities — Kashmiri Muslims and Kashmiri Pandits — are victims of the lingering conflict. As a journalist friend of mine remarked, holding Kashmiri Muslims responsible for the Pandit expulsion is like blaming the victims of a tsunami for the sufferings of those affected by a tidal surge.