“Kneeling beside her, poised over her body, I am massaging her neck... I learned the technique from a fellow prisoner of war... And suddenly I’m terror-stricken: her eyes have glazed over... and a tiny portion of her tongue is visible, strange and calm, between her lips and her teeth... I stand up and I cry out, ‘I’ve strangled Helene’.”

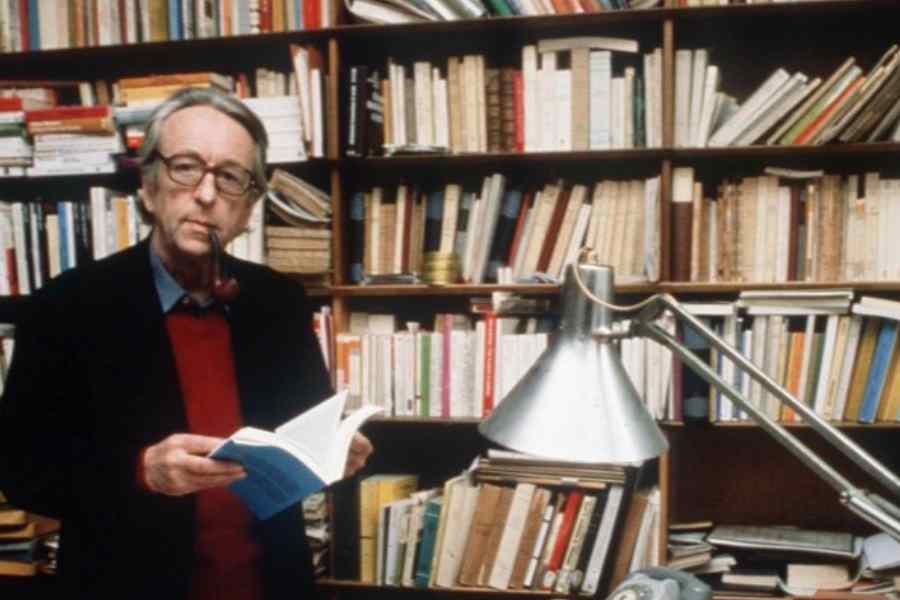

These are lines from the posthumous memoir of the French philosopher, Louis Althusser. Althusser killed his wife: that murder, committed in a fit of depression, gave him a life in clinics for the rest of his years rather than incarceration. But the fact remains that he had strangled his wife, the sociologist and activist, Hélène Rytmann-Légotien. It is also a fact that his works of political philosophy offer some of the most trenchant insights into power and control in the modern State and the free market.

I regularly use, cite, and teach the writings of Althusser, particularly his canonical essay on the ideological forces at work in the family, church, and educational institutions. So do hundreds of writers, thinkers, and academics around the world. None of them is possibly ignorant of the fact that he’d killed his wife. Indeed, that sensational fact about his life is far more widely known than his intricate and often challenging works of political philosophy. What is this great irony of reading power and oppression in society through the works of a man accused of uxoricide?

The philosopher, William S. Lewis, looks long and hard at this question. There is, he says, the externalist approach to this which invokes biographical facts to evaluate the relevance of a philosopher’s work to particular problems. The internalist approach, on the other hand, claims that philosophy would be much poorer if we expunge the works of vicious philosophers. But it is the mutual relationship between the two approaches that is key here. Althusser’s case is complicated by the fact that not only are his ideas “deeply and presciently feminist but that feminist theorists have made interesting and productive use” of them, including Laura Mulvey on visual pleasure and Judith Butler on gender, which have changed directions for entire disciplines. The fact is that Althusser probably would not have become a communist were he not imprisoned in a Stalag or if he never met Rytmann-Légotien. At the same time, the importance of his idea of communism as a condition of mutual respect in a climate of non-exploitation can also be debated outside the facts of his life. One doesn’t need to exclude the other.

The personal life, particularly the ethical violations of writers and thinkers, can make us reject them on a personal level. However, a crucial factor is how such violations affect our understanding of the principles they have come to signify. When the writer and academic, Mukoma wa Ngugi, announced on X that his father, the iconic Kenyan writer, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, had “physically abused” his late mother, Nyambura, it helped us see the cultural narratives about sub-Saharan Africa in a new light. “We have always,” wrote the Nigerian academic, Ainehi Edoro, “told the story about African literature with people like Ngugi as the protagonists. What is lost in this triumphal history are the traumatized children and neglected wives, homes ravaged by the twin power of patriarchy and colonial violence.”

What matters is what they stood for. The hauntingly resurfaced stories of the deceased writer, Alice Munro, looking away from her husband sexually abusing her minor daughter from her previous marriage can — and will — fill us with shock and disgust. But what is crucial for cultural history is that Munro has been celebrated — and awarded the Nobel Prize — for the psychological complexity of the feminine ‘Gothic’ as embodied in the tragic and eroticised female lives depicted in her short stories. Is her female Gothic purely a picture of oppression? This is the traumatising question with which we are now left.

Saikat Majumdar’s most recent book is The Remains of the Body