Is it difficult to remain friends with people whose political views are different from our own? How do such ideological differences play out in the family? The workplace? Such thorny questions are as old as human society. But over the last decade or so, they have taken on an unbearable urgency as various forms of extremist ideologies around the world have polarised almost every segment of society.

For me, the watershed year was 2016, the year I returned to a university landscape in India that seemed caught in the paradox of promise and repression — a higher education boom threatened by the suppression of freedoms across public universities. Soon, Donald Trump became the president of the United States of America and my social media timelines became flooded with shock and dismay from liberal and left-leaning American friends. The popular vote on the British exit from the European Union — Brexit — brought similar utterances from such groups of friends in the United Kingdom. We were still learning that by playing with algorithms, social media keeps us in our bubbles of preferred views and opinions. From the bubble, the rising noise of right-wing ideologies seemed like an inchoate howl. But it took just a few years for that howl to become the mainstream hosannah to the idea of a new India.

Living in Delhi, the city of power and policy, and in Gurugram, a key hub of corporate India, is to be blinded by this gloating. A visit to a dentist becomes a long conversation with a young, intelligent, Western-educated professional who tells me: “Ten years ago, the only opinions you could express socially were liberal ones.” Looking out of his shiny glass wall to the dazzling malls past the sprawl of chawls, he continued, “Now thank god we can celebrate the progress of the nation under this government — everything for which you needed to shop abroad is now here.” I hear more voices of pride and celebration whenever I go outside my usual literary and academic circles, even while mingling with the parents in the earthy, alternative school of my children.

Neither are the children spared. My fourteen-year-old daughter ends a deep friendship that lasted beyond two years: among other things, her friend had views on Muslims that my daughter felt she simply couldn’t live with. I can’t help but think — were we more tolerant as children, or just indifferent? Or were times less divisive? Growing up in Calcutta in the last decades of the last century, the pet rivalry between the CPI(M) and the Congress was diluted into a joke by a commonly-shared mistrust of all politicians and cynicism about their promise and performance. All these decades after Independence, neither nationalism nor communism felt substantial enough to be ideologies in serious mutual conflict. Why is it then that today everything seems to be fiercely at stake? Religion, national pride, freedom, development, progress? A recent article by Nissim Mannathukkaren is terrifyingly titled “The personal toll of political vitriol: A decade under Modi has torn apart families, friendships”.

In James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the autobiographical novel about the writer’s coming of age, one of the most terrifying moments of education is that famous Christmas dinner scene. The young Stephen, at home from boarding school for the vacation, watches with fear and bewilderment as his father, uncle, and his father’s friend break into a fierce fight at the dinner table with his strong-willed aunt, Dante. A devout Catholic, Dante is hostile towards the late Irish freedom fighter, Parnell, who had earned the wrath of the Catholic clergy of the nation due to his unconventional personal life. As Dante screamed that god and religion must come before anyone else, one of the men (all Parnell supporters) said that should that be true, then Ireland should not have god at all. Dante left the dinner in a rage, leaving the man weeping at the table for his dead hero.

Joyce’s narrative voice in that scene says much about what national politics might mean to children, or how it may flow into the inner recesses of our domestic sphere, blowing them up. Childhood has also long occupied me as a writer, as a time of blind and honest sensations of happiness as well as trauma. Childhood and early youth also tell much about unlikely friendships. Friendships formed these days — the school and the college years — are the likeliest to survive political and ideological differences that come up later in life. And not just the politics of parties — sometimes it fights and lives with conflicting views on gender, race, sexuality, social divisions and hierarchies of all kinds. What else can account for people’s irritation with such fights on housing community WhatsApp groups but their amused, if exhausted, tolerance of the same conflicts on school and college WhatsApp chats?

The irrationality of ideologically opposed friendships haunts me. Is it desirable? Is it possible? Where do we draw the line? Religion? Nationalism? The inequity of social identities? Is prejudice compatible with love? What happens when a family member articulates caste or religious prejudice? What if it’s a loved one? Do they remain beloved, or do we mark ourselves selfish for loving them? What is the unfairness of primal connections that supersede ethics applied otherwise — blood, the kinship of youthful bonds?

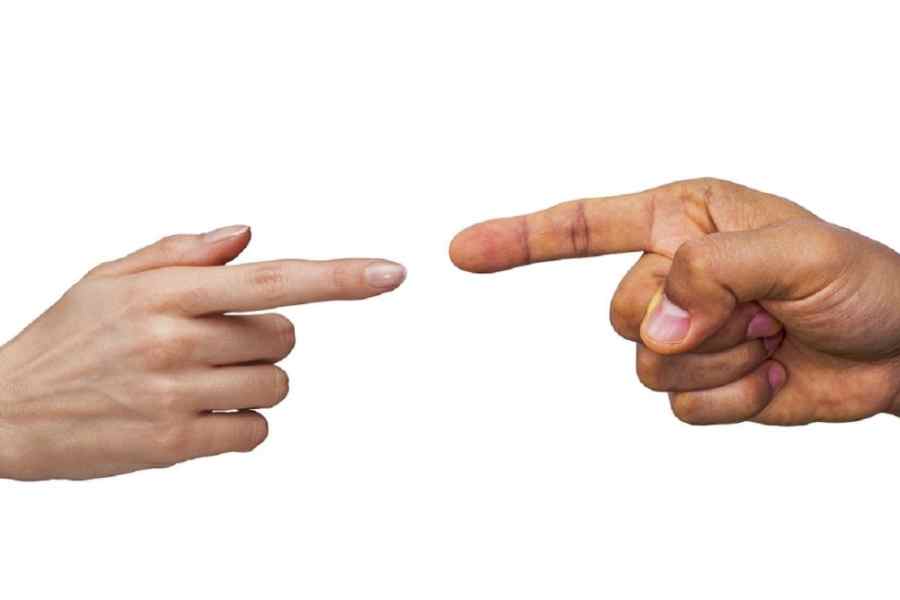

The key common feature that human beings share is difference, that, like an unchanging cliché, make and break relationships, from marriage to Parliament. The essence of democracy is about how to turn difference into a productive force. In a recent interview in The Wire, Ramachandra Guha described how Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel overcame their differences to turn their contradictory personalities into richly complimentary forces that brought a newly-independent nation together. The lifeline of democracy is the simultaneous existence of difference and its synchronisation as preconditions of each other. That too seems to be the unmistakable message sent this time by India’s electorate to the nation’s elected leadership.

Saikat Majumdar’s most recent book is The Remains of the Body