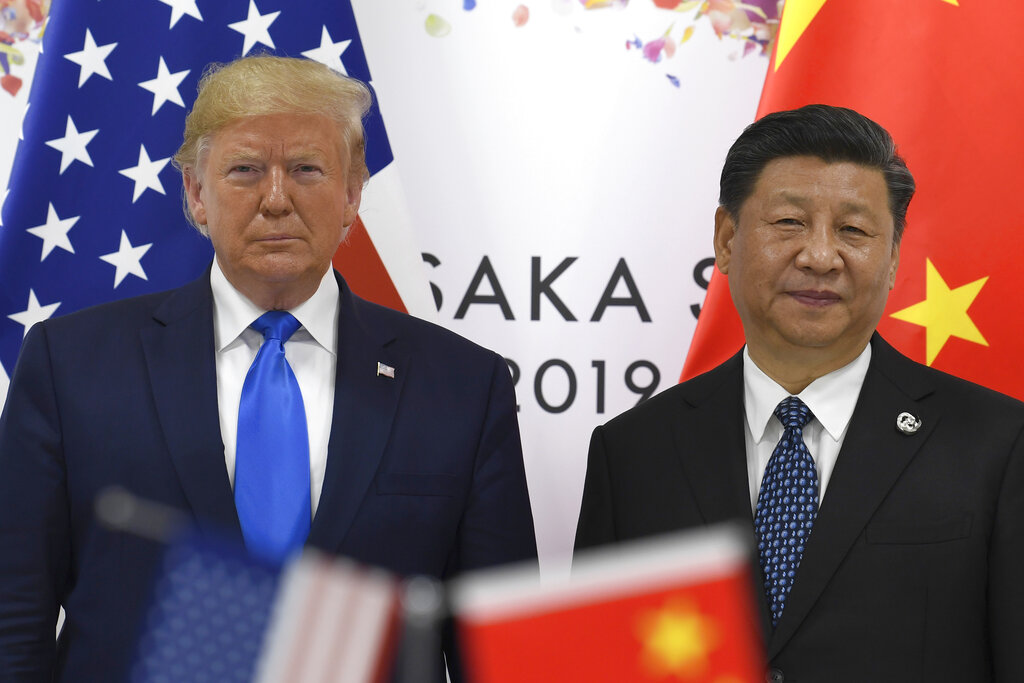

Nation states, like four-year-olds, find it hard to admit they are wrong and apologize. Adult intervention often helps, but all Japan and South Korea have is the US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, who tried and failed. So the trade war between the two grows and festers. There are obvious similarities with the trade war that Donald Trump is waging against China, with Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, playing Trump’s role: blustering bully with no clear game plan. Like Trump’s trade war, the Japan-South Korea clash threatens to destabilize both East Asian security and the global market.

Yet the confrontation between Tokyo and Seoul is not really about trade at all. It’s about the difficult history of relations between an ex-imperial power and its former colony. Japan is existentially in the wrong in this relationship, because it seized control of Korea in 1905 and ruled it, sometimes with great brutality, until it was defeated in World War II in 1945. But Tokyo doesn’t like to be reminded of all that, and claims that it discharged whatever moral debt it owed when it paid $500 million to Seoul in 1965.

Almost all the money went into building South Korea’s new export industries. Japan offered to pay compensation directly to Korean individuals who suffered forced labour and other injustices during the War, but Seoul preferred a lump sum, spending almost all of it on development. The victims got little or nothing. The resentment this caused was diverted onto Japan, which had driven a hard bargain and failed to issue an apology. Anti-Japanese hostility is thus always bubbling away underneath.

Fast forward to last October, when South Korea’s apex court ruled that the lump-sum, government-to-government deal of 1965 did not cover damages for the mental anguish of individual wartime labourers. Subsequent rulings have authorized South Korean individuals to claim compensation from the Japanese industries that used their labour by forced legal sales of those companies’ assets in South Korea. President Moon Jae-in did not seek this ruling from the court, which is entirely independent. The court was clearly stretching the law almost to breaking point, but in practical political terms he could not disown it.

Japan, on the other hand, was horrified. Accepting it would open the door to huge claims from people who had suffered ‘mental anguish’ from the Japanese occupation in all the other countries Japan invaded between 1937 and 1945. It also felt betrayed: half a century ago it had paid out a lot of money to extinguish further claims like these. There has never been much love lost between Japanese and Koreans, but the two countries have almost always managed to keep important issues like trade and national security separate from the emotional flare-ups. Last month, however, Abe completely lost the plot. He began imposing restrictions on Japanese exports to South Korea.

They are relatively minor restrictions. Three classes of chemicals essential to making semi-conductors that South Korea buys from Japan now require export licences. A minor bureaucratic hurdle, unless Japan stops approving the licenses (which it has not done). More recently, Japan has removed South Korea from its ‘white list’ of countries that are allowed to buy goods that can be diverted for military use with minimal restrictions. Again, no big deal. Just another little hurdle to cross, meant to rebuke and annoy South Korea, not to cause serious injury.

But it has been very successful in annoying South Koreans, who have spontaneously organized an effective boycott of Japanese goods. And petty though its origins may be, this confrontation is now raising the prospect that these long established trading partners, both closely allied to the United States of America and both anxious about China’s rise and the threat of North Korea, are going to have a real trade war. With a little help from the bigger trade war Trump started with China, this may be enough to tip the world economy into a deep recession.