The release of the cheetahs from Namibia has been at the centre of major public events and debates in a manner unusual for India. The cheetah project has led to debate on the wisdom or otherwise of the scheme. There has been a range of views, as should be the case. Missing in these discussions is a wider sense of history. It is almost as if histories of and with nature are being written on a clean slate. As it turns out, the reverse may well be the case.

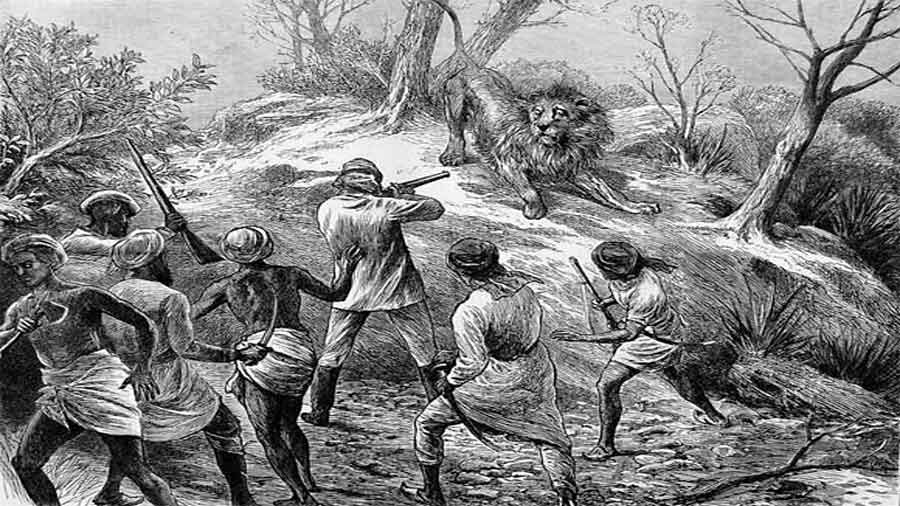

There have been both hits and misses in rewilding locally extinct mammals in parts of India. Just over a century ago, Kuno saw such an experiment. The site itself is redolent with history as it was a hunting reserve of the Scindias of Gwalior. Madhavrao Maharaj, a reform-minded man, was an ardent sportsman who took Lord Curzon no less out on tiger hunts. Kuno, where lions were originally to have been given a second home and is now the first site of cheetah rehabilitation in Asia, was the site of introduction of lions from East Africa in 1910 and 1920. Colonel Kesri Singh, who was in charge, hoped to breed enough for the ruler and the guests to bag trophies.

The lions bred, but many turned on cattle and humans and were eventually shot dead or killed. But the deeper reality is that princes sought to renature the forest and uncultivated lands to renew their legitimacy. But Colonel Singh was always a sceptic. He would later try and establish that Kuno’s resident tigers had killed the lions. Even if that were sometimes the case, the lions had been shot as they turned on cattle and villagers.

A lion was shot in Panna. It was a biological success — in terms of breeding and rearing of lions — but a failure in social terms. Conflicts with humans led to an early end of the first-ever transcontinental big cat.

The Indian Board for Wildlife met first in 1952. Besides admitting to the extinction of the cheetah, it called for a second home for the lions of Gir forest. Three animals were taken to Chandra Prabha, a small sanctuary near Varanasi. Dr Sampurnanand, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, was present, and he expressed the hope that the lions would be an attraction as important as the holy city and that of Sarnath. Again, the animals bred but were eventually poisoned or shot.

The lion project of the 1950s failed in part because there were no laws to protect them or the wild prey. The sanctuary and nearby forests had cattle herders but there were no schemes to compensate them for the loss of their livestock.

Why rulers invest time, energy and resources in such projects is worth asking. In the age of Empire, shikar or sport-hunting was a key marker of power for princes and imperial officers. In bringing back the lion, Gwalior was asserting its rulers’ vision of rule over nature as much as over the peoples of the forest.

Exclusion did not work as the animals were peripatetic. Cheetahs will need more living space in the long run if the attempt is to succeed. The 750-square-kilometre park now has no human residents. The 24 villages, which moved in the mid-1990s, are well beyond but many await land rights as has been shown by Asmita Kabra of Ambedkar University.

The cheetah habitat is over 3,000 sq. km but has rural settlements. Will there be attempts at cohabitation here? The lion relocation projects of the last century were instances of biological success and social failure. There are questions here beyond that of the cheetah.