We have heard liberal platitudes for centuries. The lecture halls in Oxford and Cambridge, in Harvard and Princeton, have resounded with Western liberal humanism and Enlightenment philosophy. Liberalism and justice are subjects often spoken of in a spirit of concern but lack the underpinnings of praxis as is apparent from the dark history of imperialism and racial discrimination.

Thinking of colonial history and its relevance to the emerging, multipolar world, my mind goes back to the 1970s when I approached the chairman of my department with a proposal to begin a course in Postcolonial Studies, to which he exclaimed with horror that I remain confined to the Great Tradition of English literature, the staple of English Studies across the colonised world. There was an arrogant overtone of an ingrained mindset that was strictly in line with the dominance of Western canon in the universities. He, undoubtedly, had failed to grasp the problematic nature of selective reading of history by which one nation begins to manufacture an image of liberal munificence or of cultural fascination while the rest of the world begins to fall in line. The imposition of political and cultural narratives of exceptionalism or idealism inspired by the United States of America, for instance, had military and economic undercurrents of coercion in Latin America, the Middle East, not to mention Africa and Asia. However, America’s holier-than-thou attitude was a strategy of deluding the world into thinking that its military interventions were inherent to its stature as the global saviour of democracy.

Disregarding much of the historical truth about non-Western powers and their economic supremacy, or, say, the idea of egalitarianism, justice and religious tolerance advocated by Akbar in India in the 16th century, the West had strategically manufactured the narrative of Social Darwinism or racial superiority. The idea of democracy or human rights was cleverly highjacked with the motive of reflecting the façade of a liberal worldview unmindful of the fact that its origin lies elsewhere. For instance, the very impetus behind the civil war in the US lay in the anticolonial resistance movement in the 19th century in Haiti.

The post-Second World War movements of decolonisation and national independence ushered in a new era of Postcolonial Cultural Studies, a project imbued with the potential to dismantle Eurocentric, unipolar strategies of controlling the colonised mind and rewriting their histories and their economies from a Western perspective. Self-determination thus became the basis of challenging Western norms.

The way we understand the world today must be seen within the historical context of the past when the West dominated the world economically and militarily. Gradually, the culture of ‘writing back’ from the periphery began to counter the Western-centric perspective, affirming its decisive role in disturbing the old world order with considerable contributions to the history of ideas. Mainstream histories from the ‘centre’, therefore, clashed with disciplines that underscored the implication of non-Western thinking accompanied by the flow of ideas more dialogic and plural than the presumptuously self-congratulatory Western hegemonic discourse and its ‘civilising mission’. But this authoritarian narrative would slowly dissipate. The parallel trajectories of Postcolonial Studies and the rise of non-Western nations were underpinned by a tangible shifting of the balance of power, a seismic upheaval that continues to this day.

The understanding of the global order and predictions about the future had been restricted over a long stretch of time to Western scholarship that was blind to the limitations of an increasingly inadequate and narrow world view. A parallel order gradually evolved, challenging the Western perspective in various studies, from economics to political history, from liberal arts to philosophy and anthropology. It echoed the shift in the balance of power visible in the rise of Asia.

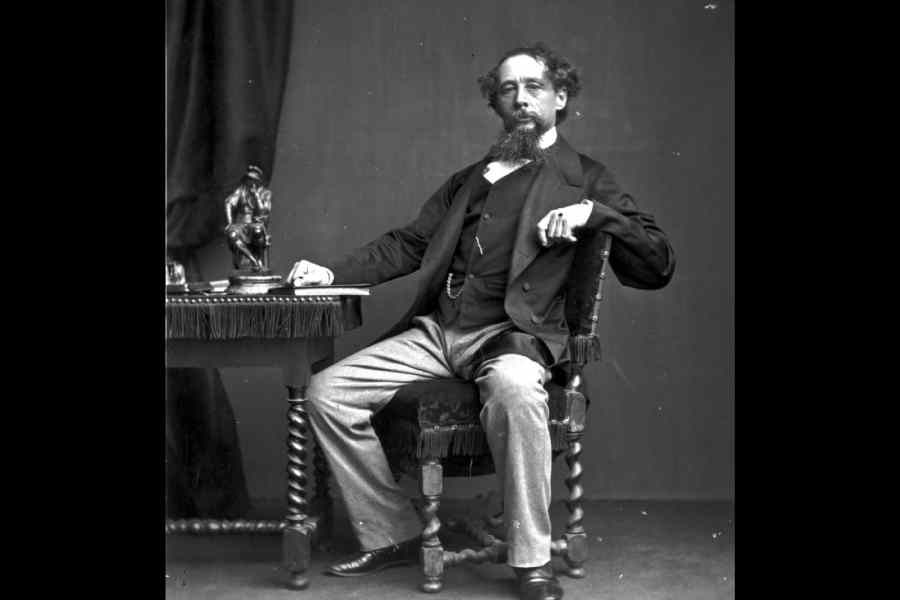

The future of the international order thus began to move towards the allocation of the rightful place deserved by non-Western cultures, resulting in the end of a Western narrative that, in its supremacist ideology, began to be regarded as a fleeting deviation soon to be upturned not only by the rise of Postcolonial African, Asian or Latin American Studies but also by the rapid rise of emerging economies and political powers that began to have a tangible say in world affairs. This resonated in the way Postcolonial Studies dethroned Milton, Dickens and Thackeray. Even Shakespeare was now no great ‘shakes’ as writers like Rigoberto Menchú, Salman Rushdie and Elif Shafak began to occupy centre stage. Interestingly, the G7, NATO, and the OECD similarly began to confront the rise of effective and parallel initiatives such as G77, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation that would dilute the stature of the existing initiatives of the wealthy nations and simultaneously enhance strategic autonomy.

The world must realise that the greatest threat to stability lies more in America acting as a hegemon than in nations like China, North Korea or Iran. The trend of multipolarisation envisages a more peaceful world order with a balanced military and economic power. China-centred regional initiatives are not intended to confront the West but to work within the existing structures so as to reduce excessive dependence on the West. One would have to wait and watch if the post-unipolar world will be more durable with the emerging nations contributing new ideas in the areas of finance, trade, security and diplomacy as well as in art, literature and culture. The lesson to be learnt from analysing the issues of moral and philosophical relevance to international relations is to try and avoid reproducing the effects of discriminatory power. No one can, with any certainty, lay down a single, universal moral philosophy.

Shelley Walia has taught in Panjab University