The scope and meaning of Bengali culture and who are its rightful custodians were themes that played out in the recent elections to the West Bengal assembly. Although complex issues of culture and identity are never settled by the proverbial show of hands, their appearance in competitive politics does indicate that popular concerns are never confined to bread-and-butter issues alone. This, of course, isn’t exclusively limited to voluble Bengalis. In the past five years or so, Western democracies have witnessed sharp divisions on questions of history, language, sexuality, faith and, most important, national identity. As immigration has altered the ethnic profile of countries, an increasing number of people are asking the question the Harvard professor, Samuel Huntington, posed to fellow Americans in 2004: “Who are we?”

For the past decade or so, maybe longer, a small group of people attached to the ideological ecosystem of the Bharatiya Janata Party have attempted to popularize the commemoration of June 20 as West Bengal Day (Pashchim Bongo Dibas). This year — and despite the inability to secure political power in the state — they managed a significant breakthrough. Having secured recognition as the official Opposition in the assembly, they observed West Bengal Day at the gates of the assembly in the presence of MLAs and the leader of Opposition. There, the demand was made to have West Bengal Day put on the official calendar. Additionally, it was suggested that the names of all those MLAs who had voted for the creation of West Bengal in 1947 be inscribed on a tablet on the assembly premises.

The fulfilment of the demands must necessarily wait for a change of political dispensation. The ruling Trinamul Congress is not merely opposed to the idea of a West Bengal Day but is seeking to rename the state altogether. However, by bringing the question of the state’s name and the history of its formation into momentary focus, the BJP may have succeeded — albeit in a modest way — to resurrect a troubled, awkward and increasingly forgotten chapter of history.

There were two votes on June 20, 1947. In the first division, the Bengal Legislative Assembly voted 120-90 to incorporate the entire province in the new state of Pakistan. A separate meeting of legislators from the non-Muslim majority districts of Bengal, however, voted resoundingly to seek a partition of the province and remain in India. All the Congress members from West Bengal voted for dividing the province, as did the two Communist members, including Jyoti Basu. The Muslim League members were equally united in wishing to avert the separation of the Hindu-majority districts. Their version of East Pakistan included the whole of Bengal and Assam — a reason why Mohammed Ali Jinnah subsequently lamented that he had been given a “moth-eaten Pakistan”. Since the British prime minister, Clement Attlee, had announced on June 3, 1947, that the legislatures of Punjab and Bengal could opt for partitioning their respective provinces, the vote on June 20 signalled the creation of West Bengal, although its formal borders awaited the Boundary Commission award at the very last minute.

The creation of West Bengal on June 20, 1947, implied two separate rejections.

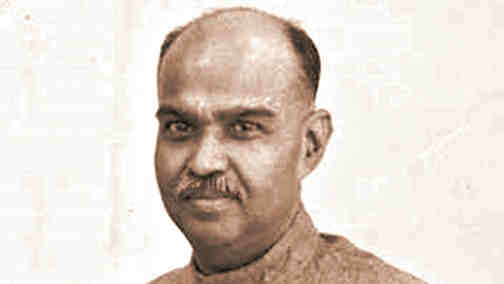

First, the Hindus of the province were emphatic in their opposition to the incorporation of the province in Pakistan. This included the representatives of Hindus living in the Muslim-majority districts. The only leader of some consequence who broke rank was Jogendra Nath Mandal, a Namasudra leader who joined the Muslim League and was made a minister in the interim government. Simultaneously, all the Muslim legislators voted to have the entire province incorporated in Pakistan.

The Hindu case for partitioning Bengal was forcefully expressed by the Hindu Mahasabha leader, Shyama Prasad Mookerjee, in a letter to the viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, on May 2, 1947. If, argued Mookerjee, “Muslims being 24 per cent of India’s population constituted such a formidable minority that their demand for a separate homeland and state became irresistible, surely 45 per cent of Bengal’s Hindu population was a sufficiently large minority which could not be coerced into living within Pakistan against the will of the people”.

Secondly, in the aftermath of the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, a romantic aura has been built around the proposal for a sovereign, united Bengal mooted by the Muslim League’s H.S. Suhrawardy and the Congress stalwart, Sarat Chandra Bose. The proposal, however, secured no backing from either the Muslim League or Congress leaderships, with Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel rebuking Bose for being detached from reality. Moreover, it was resolutely opposed by Bengali Hindus — still in a state of shock after the Calcutta killings of August 1946 and the carnage in Noakhali a few months later. It was felt that the Suhrawardy-Bose proposal was a back-door scheme for securing all of Bengal, but particularly Calcutta, for Pakistan.

The suggestion, proffered after Suhrawardy acquired a new avatar as the upholder of Bengali nationalism in East Pakistan, that the proposal indicated an embryonic, non-sectarian, cultural nationalism of all Bengali-speakers is not backed by any meaningful contemporary evidence. The movement for Pakistan in Bengal may not have been centred on the creation of an Islamic state — as certainly was the case in parts of North India — but the sense of Muslim pride that was invoked was built on an emphatic rejection of Hindu cultural dominance. As the historian, Neilesh Bose, wrote in the context of Abul Mansur Ahmed, a Bengali writer and literary figure prominent in the movement for Pakistan, “He did not exactly support a ‘divided Bengal’, as much as he opposed a Bengal where Muslims would be politically and culturally under-represented. Transforming Bengal into the Purba Pakistan portion of greater Pakistan would provide the means to fully represent Bengali Muslim cultural and political potentialities.” In short, Bengali Muslims would now dominate.

At the grassroots, these impulses translated into a form of ethnic cleansing, as was first experienced in a horrifying fashion in Noakhali in 1946. In his resignation letter from the Pakistan government in 1950, Jogendranath Mandal stated that despite the Nehru-Liaquat pact, the East Pakistan government “is still following the well-planned policy of squeezing Hindus out of the province”. Despite the formation of Bangladesh in 1971, the squeeze has continued unchecked.

The circumstances and the forces that led to the formation of West Bengal — in effect, as a safe haven for Hindus of the entire undivided Bengal — has proved to be awkward in a contemporary context. The Left, which once spearheaded the movement for the rights of refugees, preferred focusing on the grim condition in the camps rather than ask what created the refugee problem in the first place. This denial persists among Bengali intellectuals.

Within Bangladesh, there is an understandable squeamishness over the history of the widespread political and cultural appeal of the movement for Pakistan among Bangla-speaking Muslims. The political career of Suhrawardy from the early-1950s until his death in 1963 is celebrated by the Awami League. But it fits uncomfortably with his pre-1947 record as an Urdu-speaking stalwart of the Muslim League. Suhrawardy, despite being a native of Midnapore, learnt his admittedly ‘exotic’ Bangla as late as 1937.

History is invariably viewed through the prism of the present. There are political gains in portraying Bengali culture and politics as an unending saga of syncretism and progressive thought. However, the turbulent history of the second partition of Bengal, the uncertain plight of minorities in neighbouring Bangladesh and the discernible demographic transformation of West Bengal fit uneasily into the cultural nationalism of Mamata Banerjee. They become even more jarring when the political rationale behind the creation of West Bengal in 1947 is sought to be resurrected from the pages of censored history.