Like countless others, I, too, am utterly delighted that the West Bengal electorate has halted the fascist juggernaut of Narendra Modi and Amit Shah although, naturally, disappointed at the decline in the vote-share of the Left. The latter, however, has been a price demanded by the former.

The 50th anniversary of the liberation of Bangladesh is being celebrated this year, an event that had refuted in practice the two-nation theory of M.A. Jinnah that underlay the formation of Pakistan. Jinnah had privileged the Islamic identity over all other identities, but the formation of Bangladesh was a blow against this; it amounted to privileging the Bengali identity over others. The linguistic-regional identity in short had triumphed over religious identity in the creation of Bangladesh, refuting the notion that the ‘Muslims’ of undivided India constituted a nation.

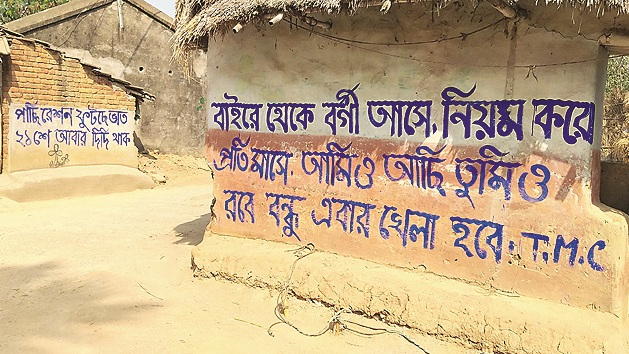

Something similar has happened in West Bengal in the recent elections: the linguistic-regional (Bengali) identity has overcome appeals to the religious (Hindu) identity. There were, no doubt, many factors behind Mamata Banerjee’s victory, but the enduring image was of a linguistic-cultural entity, called Bengal, being invaded by ‘outsiders’ (bahiragata, referring to outside electioneers, not settlers from other states), who brought with them not only alien cultural traits but even the scourge of the coronavirus. Mamata Banerjee emerged as the champion of this linguistic-cultural assertion, a symbol of Bengal’s resistance against invasion by ‘outsiders’, just as on the earlier occasion Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had donned that role on a much bigger scale.

In this clash between identities that became overarching, the Left got squeezed out, just as the Left in Bangladesh — not a mean force in earlier times with popular leaders like Maulana Bhashani — had got squeezed out.

This is not to say that promoting the linguistic-regional identity itself is foreign to the Left; indeed the very idea of forming states on a linguistic basis was a Left idea (since “nationalities” in Communist theory are defined on the basis of language). In accordance with this, the Left had led the ‘Vishalandhra’ and ‘Aikya Keralam’ movements and participated in the ‘Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti’ agitation. But this was at the stage of the formation of states; once states have been formed broadly on a linguistic basis, the Left would find it difficult to project an argument of the kind Mamata Banerjee did, that “Bengal’s linguistic-cultural identity is under threat from ‘outsiders’.”

The invocation of ‘nationality’ consciousness in the Bengal elections also promoted ‘secularism’ in a different way. The argument now advanced for secularism was that it went against Bengal’s tradition, not just that it was a desirable thing. A very senior communist leader had once told me, half-jokingly but with a core of seriousness: “there are no more than a thousand people in the country who are genuinely committed to secularism; but that is quite enough for defending secularism.” This was before the era of neoliberalism, which made the intelligentsia, a major beneficiary of it, lose its credibility among the masses. The ‘thousand’ who were to be found within its ranks would no longer suffice and the need arises for a fresh prop for secularism other than its sheer desirability. This came to the fore in the Bengal elections.

In regions with strong linguistic-cultural traditions, as in Bengal or Tamil Nadu or Kerala or indeed the entire rim of states outside the Hindi heartland (except Assam which has its own particularities), the linguistic-cultural identity can be a powerful bulwark against Hindutva’s invocation of religious identity. The Hindi heartland, however, is quite different. It is not a compact region with a single distinct language, but a sprawling area marked with variations on one basic language. Besides, there is a certain lack of cherishing of the literary tradition of that language even among the educated in the region.

When my wife had won a school prize for proficiency in Hindi, she wanted to buy Hindi novels other than by Premchand with the money and asked a well-read friend whose mother tongue was Hindi for advice; her friend’s suggestion was the novels of ‘Saratchandra’. My wife, a Bengali, had read him years earlier in the original; but the story, while underscoring a laudable absence of narrow-mindedness, also hints at an absence of a strong specific literary-cultural tradition. Invoking a linguistic-cultural identity against the Hindutva-promoted religious identity appears difficult in the Hindi heartland, which, therefore, remains open to the spread of the Hindutva ideology.

Vishwanath Pratap Singh had sought to mobilize a ‘backward caste’ identity against the Hindutva juggernaut in the Hindi heartland; but given the infinite number of castes and sub-castes, the Hindutva forces could break this unity by locating, and championing through inconsequential tokenism, the cause of some caste-group within the OBC that feels even more deprived compared to others in this category.

It is tempting to conclude from the above that there is a natural limit to the spread of Hindutva, that while the Hindi heartland remains susceptible to its influence, the rim of states surrounding it with strong linguistic-cultural traditions are less vulnerable: their specific regional cultures can withstand a pan-Indian religious-communal appeal. There is some truth in this, as the Bengal elections demonstrate; but accepting it in toto would be an oversimplification. The appeal to ‘nationality’ consciousness is not always certain to defeat the religious-communal. It may do so on some occasions but not others; otherwise, East Bengal would not have become a part of Pakistan in 1947

It follows that the Mamata Banerjee-style appeal to a Bengali consciousness will not always vanquish the Hindutva forces’ attempt to annex Bengal. The case of Bangladesh is somewhat different here. Bangladesh has had a high GDP growth-rate that has raised its per capita income above India’s. It has done so by becoming a part of international value chains, first of the North and, more recently, of China whose Belt and Road Initiative has come in handy for this process. Its economic achievement may be a far cry from the dreams of the anti-colonial struggle or its own liberation struggle, and income inequalities as everywhere else may have grown immensely, but it has at least given that country a degree of stability that has strengthened the secular forces and kept communal-religious elements at bay.

But West Bengal, like the rest of India, is mired in massive problems of unemployment and poverty from which there are no easy ways out. Neither the invocation of a linguistic-cultural unity nor the invocation of a Hindutva-communal unity will succeed in overcoming these problems. But the Hindutva forces will promise to overcome them if the electorate gives them a chance, and on that basis can come to power and infuse the poison of hatred into the State.

This is where concrete steps and strategies to overcome the economic travails of the state become necessary, such as those projected by the Left in this election. The problem with the Left had been its fixation with large-scale industry as the panacea for West Bengal’s economic woes. Large-scale industry, however, never provided much employment, not even in the 19th century. Unemployment in Britain had been kept within bounds by massive emigration of population to the temperate regions of settlement, not by employment opportunities opened up by the industrial revolution. The Left has to recognize the need for a variegated industrial structure in the state apart from showing greater awareness of the dangers of fascism. But as long as it remains faithful to a discourse that addresses seriously the problems of unemployment and poverty, it will bounce back in West Bengal.

Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Economic Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi