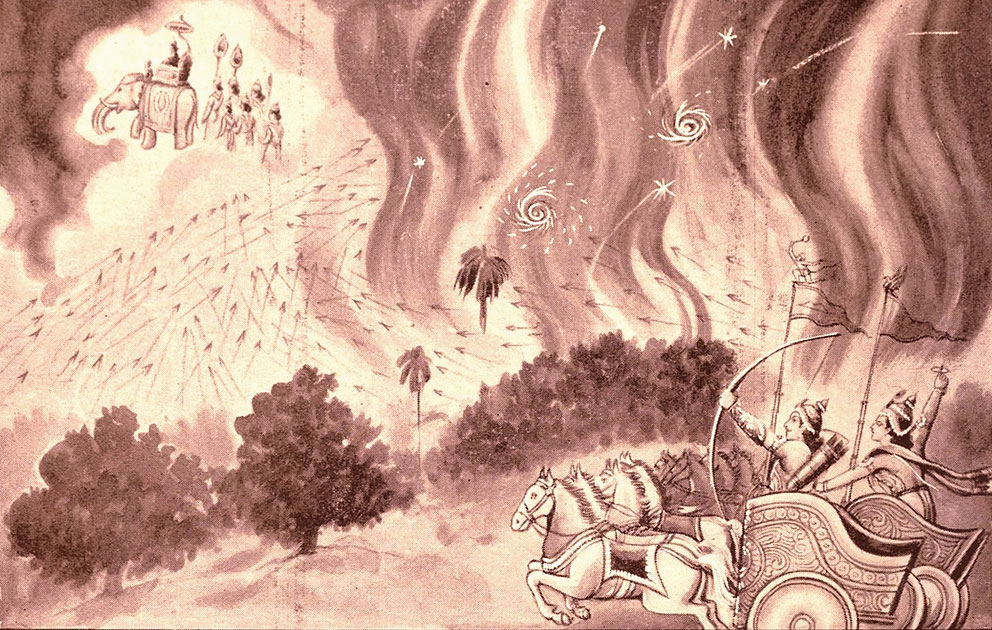

Arjuna might have found a perfect successor in Jair Bolsonaro. If this parallel seems odd, one only has to look at images of flames leaping from the Amazon and recall the incineration of the Khandava forest in the Mahabharata for clarity.

In This Fissured Land, Madhav Gadgil and Ramachandra Guha write that “Arjuna evidently wants to clear the Khandava forest to provide land for his agricultural/pastoral clan”. Bolsonaro, who came to power with the endorsement of the country’s strong agricultural lobby, has brought policy changes to make good on his campaign promise of taking advantage of the riches of the Amazon. His decisions have signalled to ranchers, loggers and farmers that it is open season on the rainforest; they sought to encourage him by observing a “day of fire” in early August, which added to the hundreds of acres of forests that are on fire.

Gadgil and Guha describe the episode in the epic as the first recorded instance of the clash between the “continual march of agriculture and pastoralism over territory held by food gatherers... who had a great stake in the conservation of the resource base of their territories.” In Brazil too, the fires are the outcome of a festering conflict between the indigenous tribes and agriculturalists over who would control the land in the Amazonian rainforest and how it will be treated.

One of the means employed to wrest control of forests and their resources is the demonization of the forest-dwelling communities. The reptiles annihilated by Arjuna in the Khandava forest are reimagined by Arun Kolatkar in “Sarpa Satra” as “Simple folk/ children of the forest/ who had lived there happily/ for generations,/ since time began.” The reptilian — repugnant — form attributed to the inhabitants of the forest is in consonance with the image of the rakshasas who tried to disrupt fire sacrifices or yagnas by sages in their woodland outposts. But the Sanskrit root of the word, rakshasa — raksha or protection — peels away the layer of prejudice. Were the rakshasas, then, just forest dwellers trying to save their resource base?

In Brazil, Bolsonaro has likened the indigenous peoples to “animals in a zoo”, claiming that the only way to “develop” them is to open their lands to commercial farming and mining. In order to do this, his government has stopped the demarcation of ‘indigenous territories’ — areas where the Brazilian Constitution allows indigenous people to live permanently and practise their cultures. Undemarcated land is open to the State’s depredations. Repeated studies and reports show that demarcated lands have the lowest rates of deforestation. Satellite data prove that even now fewer fires are burning in lands under the forest tribes.

India is no stranger to forest fires, although these do not always rage with tacit State support. Earlier this year, a fire in the Bandipur Tiger Reserve decimated hundreds of acres of forest. Notably, making up for the paucity of manpower of the forest department were some 400 members of the Jenu Kuruba, Soliga and Betta Kuruba tribes. Deployed as fire-watchers, they formed the first line of defence. Without them the damages in Bandipur would have been much worse.

Yet, the draft Indian Forest Act, 2019 seeks to change the grass-roots paradigm of forest governance by taking away the autonomy of gram sabhas. The rights of forest dwellers, the draft says, can be annulled if these are seen to stand in the way of “conservation” by paying them arbitrary compensation. Potentially, an everyday, symbiotic activity such as picking dry fallen leaves — a major stimulant in forest fires — for fuel can be seen as intent to destroy, ensuring that the individual as well as his entire community lose their rights over forest resources.

The fate of the forest dweller has changed little since the time of the great epic. In Mahasweta Devi’s story, “Paddy Seeds”, a character describes the burning of the Khandava thus: “It was not the first time and would not be the last. From time to time, with the flames and the screams of the massacred leaping into the sky, the lowly untouchable must be made to realize that it meant nothing at all...” The trappings of a constitutional democracy have failed to resolve this ancient conflict. The Amazon — the modern Khandava — thus continues to burn.