Dhritiman Chaterji and Raju Raman discuss the directions in which cinema has gone after the 1970s

Raju Raman: Maybe in the 1970s, the distinction between ‘commercial cinema’, looked down upon by intellectuals, and parallel cinema, reached a peak. Even Mrinal Sen did not care much for Bollywood cinema. I never believed in such distinctions. There can only be good cinema and bad cinema. But if we were to take it for a reality, comedy rendered itself in the form of irrelevant slapstick in mainstream cinema. Yet it was not absent in these [parallel] films…

Dhritiman Chaterji: Yes, we only have to look at films like Baksa Badal, for instance.

It was brought in with a different kind of sensibility in a very subtle way, and these [Sen, Ray and others] film-makers, in their storytelling, excelled in injecting a sense of comedy into their films.

Comedy which is not imposed, but derived from everyday life.

And there is a lot of it in Ray’s films, any film you take.

Take Tulsi Chakraborty in Pather Panchali [laughs]... This issue of parallel cinema — to some extent Ray and Sen have to take responsibility for this divorce... Ray made no secret of the fact that he had no patience for the cinema that had happened before him, Sen dismissed what he called commercial cinema. In retrospect — I don’t know whether they meant it that way — but there was always an element of self-justification. For instance, Sen dismissed commercial cinema, but during our discussion once I said to him that if one goes to the other pole, what about the cinema of Mani Kaul? This was in the early 1970s. Mani Kaul said ‘I don’t think I have a responsibility to the audience. I make films to express myself the way I think I should. And the audience can either take it or leave it’. So Mrinalda said ‘no, that’s a very irresponsible statement to me. Surely a film-maker expresses for himself or herself, but he or she also must have a responsibility to an audience’. So, on the one hand, there is a dismissal of commercial cinema, on the other, there is also a dismissal of cinema which is, let us say, very difficult. I don’t know for instance, what Mrinalda thought of the cinema of Bresson. Or Resnais... His cinema was accessible. It was different but not difficult. And this complete division between two streams, mainstream and parallel... it meant that everybody... technicians... who worked in the one did not work in the other.

So it was equivalent, or even parallel, to an amra-ora [us and them] attitude?

Absolutely. We, who were part of cinema in one way or the other at that time, all got caught up in this. Either willingly or unwillingly. Personally I, in my acting career, remember having thought that I have no role in commercial cinema. My home is the parallel cinema. Looking back, when the two streams converged, I think it did good, it was to the benefit of cinema, because talents got a chance to work in all kinds of cinema. What the merging of the two streams meant was that any technician or actor’s possibilities got expanded, got enlarged. I can personally say that only after these two streams converged was I able to do roles from which I had been cut off when I thought for whatever reason [laughs] that I just belong to…

To what extent do you think the opportunities offered by television played a role in blurring these lines? Many of the actors who were working only in parallel cinema wanted to utilize the opportunities of working in television as well, because that became the new model for livelihood for a lot of people, yes?

Certainly television played a role in shaking up this configuration which was the 1960s, 70s, beginning-of-80s configuration. Also by the 1980s, Bangla commercial cinema was taking a deep dive, aesthetically, content-wise, technique-wise; the industry was not in the best shape and, as far as business and livelihoods were concerned, television came almost as a saviour. Unfortunately, fiction in television, serials — it is true that they give people opportunity for work, but aesthetically, artistically, nothing happened.

Sen shunned mainstream cinema yet, ironically, he shot into fame with Bhuvan Shome, which was made in Hindi, and with an established actor like Utpal Dutt, and had some commercial elements in it too. So do you think there was a kind of irony over there, that people who were shunning mainstream cinema were actually getting their prominence, breakthroughs, with cinema made in Hindi with very successful actors? Do you think this business of shunning mainstream cinema was also a little exaggerated?

Mrinalda loved variety. When he made Bhuvan Shome, I don’t think it was a conscious thought-process: okay, let me make it in Hindi, okay, let me put popular ingredients into it, let me cast Utpal Dutt.

At the same time, he had a total newcomer... Suhasini (Mulay).

I think it was happenstance, there was some chemistry which caught the imagination of film-goers. But this has always struck me: Mrinalda was Bangali to the core, background-wise and everything wise, but he never, either as a film-maker or as a person, in his outlook, in his work, clung to Bangaliana. If it was Oriya, it was Oriya, if it was Telugu, it was Telugu, if it was Hindi, it was Hindi. He ventured wherever his sensibility, his instinct, led him, and what never ceases to amaze me is that when he made a film in Oriya or Telugu, particularly in Telugu, he was without any knowledge of the language, yet he was able to convince producers and find funding for his film. The issue is that he ventured. He was adventurous.

Now Utpal Dutt, he was a big name in theatre. He was a master of his own art. But his film did not make a mark when he did it as a director, and he is not the only example. Do you think that this mastery over one way of storytelling, it’s got into your veins; if you try to dissociate yourself from that and go into a new medium, it is not all that easy?

I don’t think there is one standard rule; if we look at the West, we find people who have worked with equal ease in theatre and cinema.

Bergman is an example.

Or here, M.S. Sathyu. I don’t think that there can be a rule about which is your medium. There was a time before television when cinema was the only audio-visual medium, so whether you had to tell a story, or whether you had to express your politics, that was the only medium. With television, that situation started changing: now we live in a multimedia environment and it is possible to ask if cinema as we know it, defined by a situation with a number of people sitting in an auditorium looking at a large screen, is the most basic definition of cinema, whether that is the most effective medium of political statement or is more appropriate to no-nonsense storytelling, whether ‘activism’ is better achieved in other forms that are available, not cinema.

Social media, for instance.

In this multimedia environment, live performance, the large-screen experience, television, social media, web series — a person who is working in this field as, let us call him or her a content creator, has to have the skills to go from one medium to another. I have the greatest respect for people who stick to one medium, but we have come or we are coming to a phase where a person has to move from one medium to another.

You have worked with several great directors. If you were to pick out two, or three, who stood out as far as your personal experience is concerned, who would you mention and why?

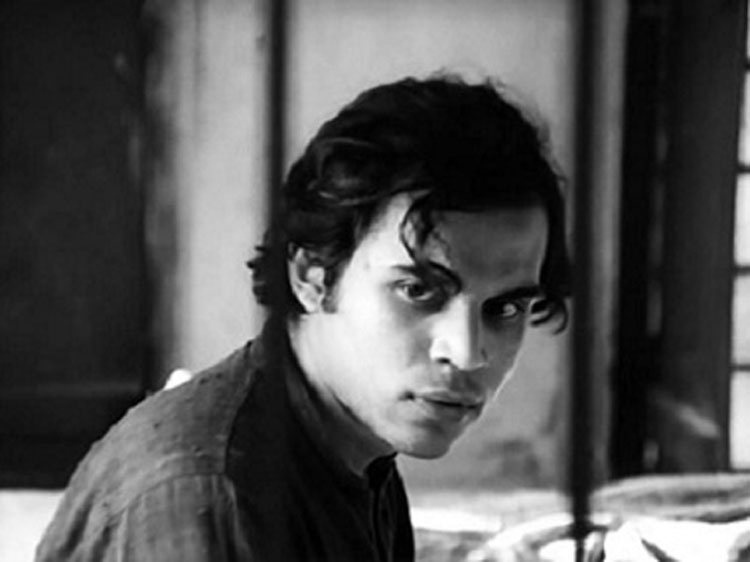

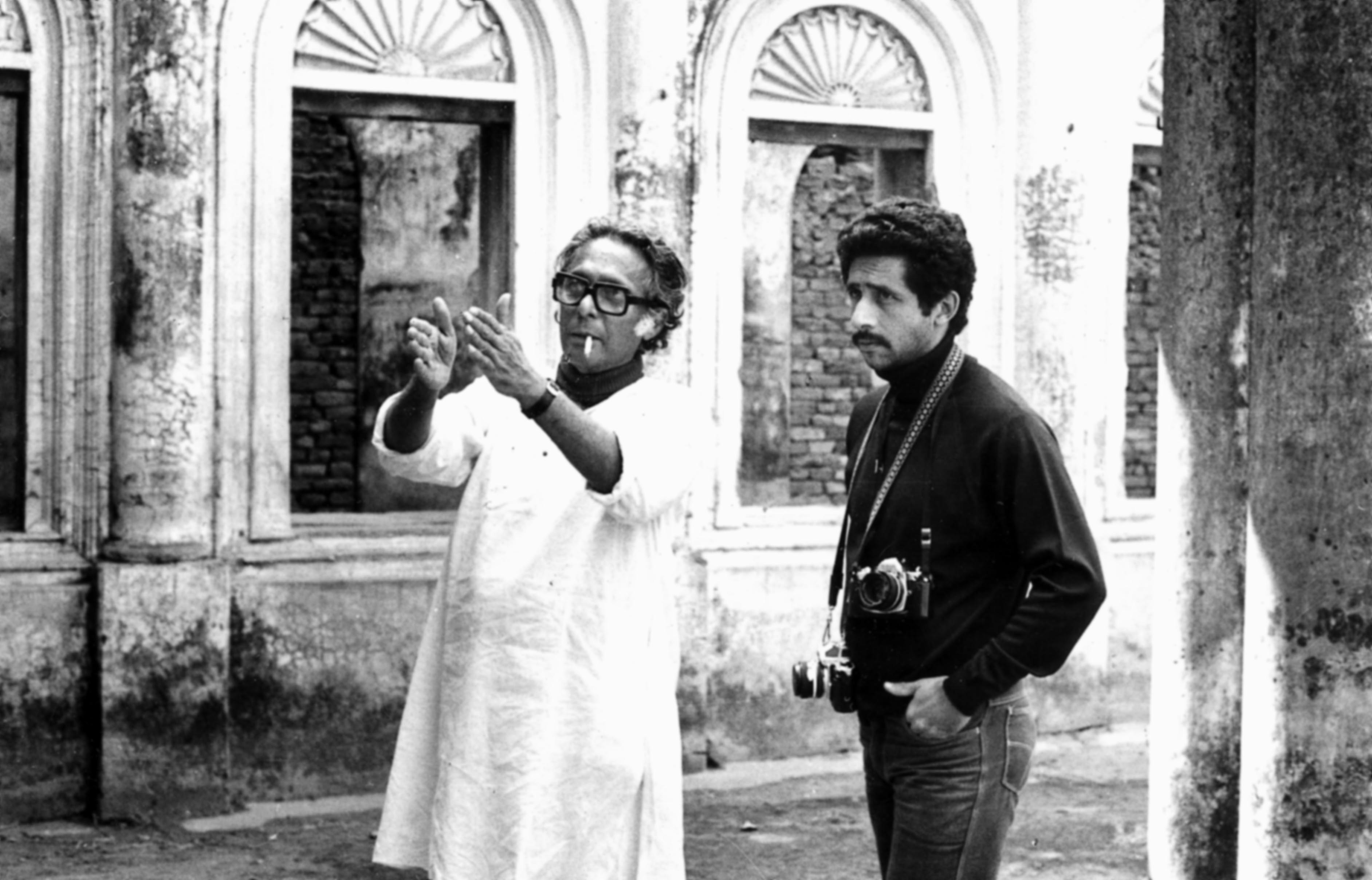

For various reasons, both Ray and Sen would be in that list. Ray, because even when I first worked with him, way back in 1970 in Pratidwandi, one of the reasons for my enthusiasm, quite apart from the acting bit of it, was to see him at work. I was familiar with his work till then, but I was very keen as a student of cinema to observe him at work — and his style of working, right from the beginning, from the pre-production stage, really was unique. And I was fortunate enough to get involved in the post-production process as well, to be present at the editing. With Sen, the one word to describe the experience would be joy... a great deal of joy, this feeling that everybody who was a part of the unit, actor, technician, everybody was literally part of that process, of the final product that was taking shape. Another director — it’s unfortunate that he has been forgotten now, partly because of his own fault — is Partha Pratim Chowdhury, who was a disciple, I think, an assistant too, of Asit Sen. And Parthada was in a way made in the Ray mould, in that he also did everything: operated his own camera, wrote his own script, did his own music, did his own editing, and so forth. He allowed himself to degenerate, but in his prime, when I worked with him in the mid-1970s, working with him was very, very difficult; he demanded a lot, artistically, emotionally... and if you knew that the man was capable of delivering quality, and if you wanted to be a part of that process, then you gritted your teeth, went through a lot of hardship and gave him what he was asking for... I am fortunate enough not to have had any unpleasant experiences. Either with units or with directors.

You have also worked in Pink, with, again, a Bengali film-maker, Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury.

Pink was intelligent Bollywood cinema at its best. It’s a completely different world from Bangla cinema. I’m familiar with that world because I worked in Black and Agent Vinod... which were all parts of this Bollywood set-up, which actually I admire in a sense, those large enterprises, for the sheer professionalism of every person, whatever he is doing. Without that those films would never get made.

Which is probably missing in today’s Bengali cinema? We’re not talking of particular directors.

The large-scale cinema in Bombay recognizes that cinema is a joint enterprise where everybody has to pull his or her weight, everybody has to be competent at what he or she does. In smaller cinema, like in Bangla cinema — I do not want to criticize anybody — in a lot of cases there is still this feeling that really the film is one person’s enterprise. For this, maybe, people like Ray and Sen, who did a lot of things themselves, are responsible to some extent. People like Buddhadeb Dasgupta, Aparna, Goutam, they created the impression that their films were theirs — again — I do not want to criticize anybody but...

They took ownership of each department.

At least that was the impression created. So the notion that cinema is one person’s, one person owns it, permeates the Bengal film industry quite a bit even now, so that the sense of involvement, professionalism, diminish to that extent.

If there was any particular film that still is in your memory of that period, which you would like to revisit again and again, which film would that be? And when you revisit it, does it have a different impact later than it had at that time?

I find Akaler Sandhane very interesting for two or three reasons. One is that it was conceived from a fragment of a story by Amalendu Chakraborty. Then it evolved as it went along, and I still find the film’s structure very complex, and I am not sure that I have been able to deconstruct or decode the film entirely... I think there are things I am still looking for every time I revisit it, so I like revisiting it. Akal was 1980, and maybe 10 or 15 years later, Mrinalda once floated in a conversation this idea: let us go back to that village; the director who was not able to complete his film, suppose he goes back, and that is after television... That revisit never happened, but it fascinates me, it’s that what-if notion, what if we had gone back there — what would have happened? What would have happened in the reality of the time, and what would have happened cinematically.

Finally, in both films in which you have acted and films in which you have not acted but have seen, what is a single sequence that is still in your memory, a sequence you cannot forget?

If I were to be able to think of one unforgettable sequence, I suspect it would come from a Fellini film, probably from Amarcord, but which one I’m not sure.

And from any of the films that you acted in?

Well, the sort of explosion, if I can call it that, sequence of Pratidwandi, overturning chairs and tables and so forth. I can recall every detail of that sequence. I think it worked very well, I think it took the audience aback, and for me personally as an actor it was shifting gear into a mode which is a) not my natural mode and b) it was not Siddhartha, the character in the film, it was not his natural mode either. He just sort of explodes into it for that one scene and then retreats into his shell again. So, a) it worked very well, and b) as an actor, it made its demands.

Thank you very much for your time.

Concluded