Privatization of State-owned assets has always been a hot-button issue steeped in controversy because no one appears to have worked out a way to hive them off in a sensible and transparent manner. About 30 years ago, the P.V. Narasimha Rao regime took the first fumbling steps down an uncharted road when it created arbitrary bundles of the shares that the Centre owned in about 30 public sector companies and sold them to financial institutions. Every single government since then has tried its hand at parcelling out the government’s stakes in public sector entities. Yet, the attitude towards disinvestment has always been ambivalent: political parties have backed the idea when in power and opposed it when in the Opposition.

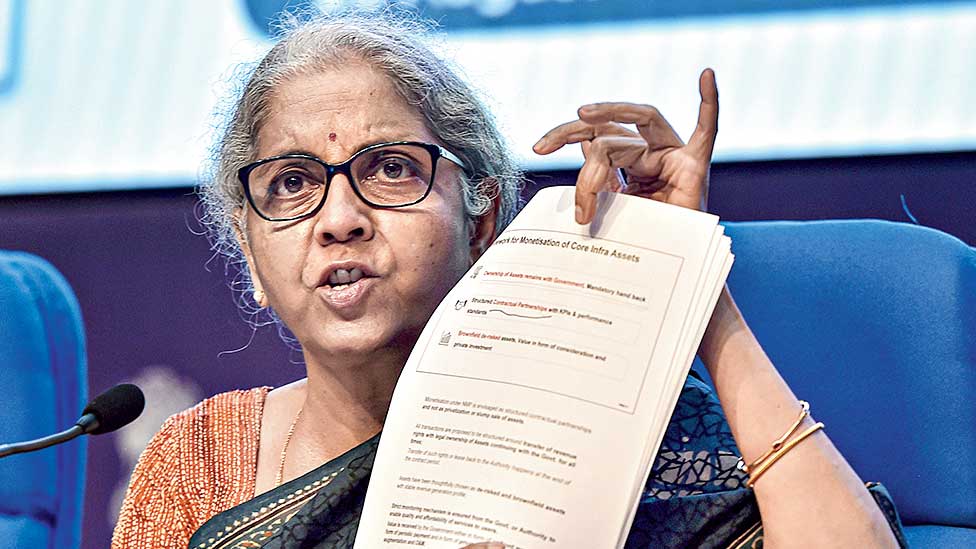

The finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, has unveiled the most ambitious programme to farm out government-owned assets to the private sector from which she hopes to raise at least Rs 6 trillion over the next four years. The National Monetisation Pipeline aims to unlock investments in public sector assets spread across 13 sectors, from roads and railways to sports stadia and urban real estate. Political rivals have accused the government of selling the family silverware — a charge that Ms Sitharaman has tried to deflect by arguing that the Centre will not be ceding ownership of the projects or the land. The NMP creates an elaborate schema for the transfer of assets and lease rights through a myriad contractual arrangements. Most of the brownfield assets will either be farmed out under toll-operate-transfer contracts or be covered by a re-imagined public-private-partnership model. But since these concessions will extend over 50 to 60 years, no one is convinced that the ownership of these assets will not change into perpetuity.

The government’s estimates of the realizable value of these assets are based on some crude yardsticks. For instance, the 26,700 km of roads that will be offered through tolling contracts is valued at Rs 1.6 trillion, calculated at a factor cost of Rs 60 million per km. The NMP says that most TOT contracts have been offered between Rs 90 and 140 million per km in the past. It may be harder to justify the monetized value of the four heritage toy train railways, including the one at Darjeeling, at Rs 6.3 billion. The government is also seeking to rebuild several colonies in Delhi that house civil servants using private capital with little clarity on how the developers will recover their investment. The Vijay Kelkar committee, which submitted a report in 2015 listing suggestions to rework the PPP model, said it might be necessary to build some flexibility into the contracts. During the United Progressive Alliance regime, many of the PPP projects were stuck because of tiresome lawsuits arising from rigid provisions. That could happen again. Mr Kelkar had said the success of concessionaire arrangements would depend on the ability of the ruling dispensation to stop “abusing its sovereign authority and act more as partners and less as clients”. Will the Narendra Modi regime embrace that sage advice?