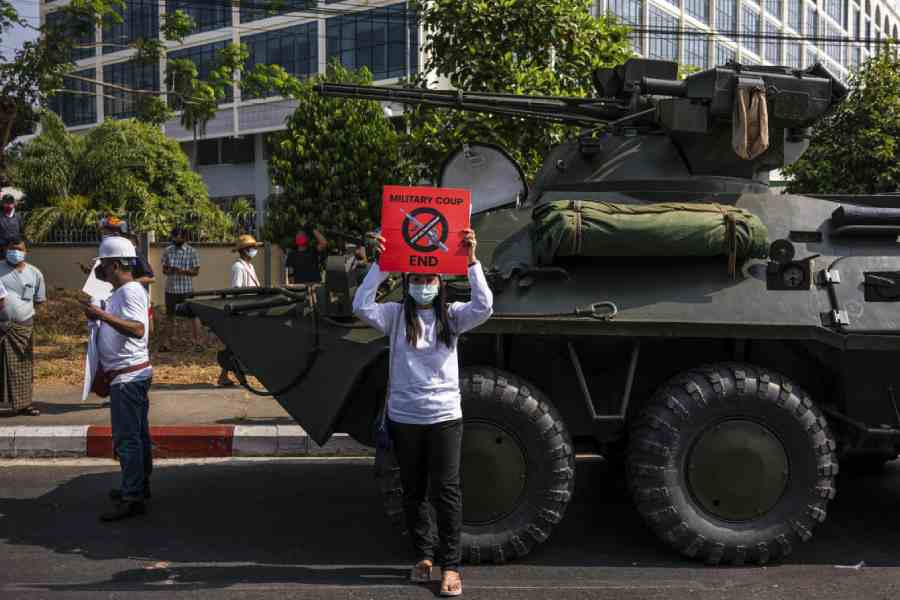

Myanmar, a country of nearly 55 million, continues to be sucked into a spiral of chaos and violence. The country, which is at a crossroads of South Asia and Southeast Asia, today bears little resemblance to what it was a decade ago when it was brimming with hope. In the nearly four years since the February 2021 military coup, there have been over 50,000 reported deaths as a result of the violent conflict and displacement with consequential transnational challenges. The figures of fatalities are indicative of a situation of anarchy.

There are no easy, quick-fix solutions given the geopolitical challenges confronting Myanmar and its internal dynamics. At best, efforts parallel to the ongoing, violent, territorial contestation can be made by domestic as well as international stakeholders to address the structural drivers of the conflict so as to bring sustainable peace and avoid ethnic fragmentation. In this context, what is required is a more nuanced political strategy towards the military. Even though the military controls less than 60% of the country — unprecedented success has been reported by the Opposition forces — the senior army leadership seems to be in no hurry to give up its control. In fact, the miliatry-led administration has already completed a controversial, nationwide census, which will be used to compile ovter lists for a general election scheduled in 2025.

Without giving the military leadership the legitimacy that it is eagerly seeking, a discreet engagement with appropriate sections of the military may be a potentially prudent strategy to address the pressing humanitarian needs. There is a need to broaden the scope of engagement as the military is not a monolithic entity. From 2010 to 2015, the former military general and president, Thein Sein, had reached out to the National League for Democracy leadership and other groups and made them a part of the electoral fold. President Sein and his team had supported efforts to promote democracy, national reconciliation, and a market-oriented economy by incorporating best practices. Relevant external players should keep open the lines of communications with a more amenable set of middle-rung officers as well as members of the senior structure, if this is not already being done. At the same time, a collective narrative from the Opposition that amplifies the message that the military’s propaganda in the Burman heartland is self-serving and anachronous is important. The military’s catchment area is the ethnic Burman heartland, which comprises nearly two-thirds of the country’s population. On January 4, Myanmar’s Independence Day, speeches are made by the military leadership to stoke memories of the anti-colonial struggle and the army is presented as a critical institution safeguarding the country’s sovereignty. To counter this, as part of a counter-narrative strategy, the delegitimisation of the military’s current actions that have led to mass, egregious human rights violations is equally important in the Burman heartland.

Myanmar is a pluralistic entity with each ethnic group having its own historical experiences and grievances that have shaped its political approaches. Given that premise, long-term institutionalised planning and coordination are a necessity among relevant stakeholders to promote trust and the notion of linked fate that may require subtle handholding from the outside without being prescriptive or patronising. Within the myriad Opposition umbrella, intra-ethnic armed groups’ contestations on various issues need to be ironed out. For instance, in January 2024, the Arakan Army seized the Chin town of Paletwa which led to tensions with the local ethnic armed group. The military’s divide-and-rule tactics to create a wedge between Rohingyas and Rakhine Buddhists on account of the forced conscription of the Rohingyas is another example.

Notwithstanding some attempts to demonstrate commitment to federalism, the political Opposition should support efforts that could help the leadership of armed ethnic groups internalise the concepts of power-sharing and resource-sharing. The bulk of the vacated area is under ethnic armed groups. This is not surprising. A 2017 study by the California-based The Asia Foundation had stated that “almost one-quarter of Myanmar’s population, hosts one or more [ethnic armed organisations] that challenge the authority of the central government.” That is why major efforts should be made to prevent an ethnic fragmentation of Myanmar and to promote the idea of common citizenship. On Rakhine, the National Unity Government, a coalition of ousted democratically-elected lawmakers and parliamentarians, had accepted on June 3, 2021 the recommendations of the Kofi Annan-led Rakhine Commission. This was a good start as it had proposed a comprehensive solution to address the concerns of the Rohingya community.

From China’s Myanmar-owned and Myanmar-led peace process to ASEAN’s ‘Five-Point Consensus’, it seems that there are no shortages of frameworks that are in circulation. In concrete terms, one should be conscious of the fact that national priorities underpin the international engagement on Myanmar. Some of the elements of ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus, such as an immediate cessation of violence, indicate unrealistic expectations. A more rigorous review is required within ASEAN, particularly by Indonesia (previous Chair), Laos (present Chair), Malaysia (future Chair) and Thailand, to leverage its collective, unique standing with both Myanmar’s military and the varied resistance groups, including ethnic armed groups. China’s shadow continues to loom over Myanmar as parts of north-eastern Myanmar depend on China for services like electricity, internet and water. China leveraged developments post-Operation 1027, a collective offensive by ethnic armed groups in October 2023, as the latter overran swathes of territory near Myanmar’s border. China was able to curb the Kokang-based scam operations whose main victims were Chinese citizens. At the same time, it contributed to the thwarting of the offensive by the ethnic armed groups in the Burman heartland by denying the armed group arms supply by closing the border.

The fall of the Burman-dominated military is not favoured by China as the ethnic armed groups in the north are perceived to be close to the West. In the pre-coup phase, routine visits of the ambassadors of the United States of America and the United Kingdom to northern Myanmar bordering China had triggered an immediate protest by the Chinese leadership.

Myanmar may have been effaced from the headlines but the conflict and the resultant humanitarian crisis there show no signs of ending. This reinforces the need to factor in the forces of history as well as political and geographical realities while formulating responses to resolve the challenges.

Luv Puri was a member of the United Nations secretary-general’s Good Offices on Myanmar