I was staying at New Delhi’s India International Centre ten days ago when I discovered, by pure chance, that a philatelic exhibition on Dr B.R. Ambedkar was on at its Art Gallery. It was a blisteringly hot day and walking at 2 in the afternoon (which is when I made this ‘discovery’) from its cool cloisters to its Kamaladevi Complex where the gallery is situated was a challenge. But a rich experience awaited me.

The large hall was empty, save a lone individual seated quietly in one corner of it, with a laptop open in front of him. He did not take particular notice of me and I got quickly absorbed in the display panels.

They were, simply, captivating. The signage was elegant, written in the finest English, with not one spelling or grammatical mistake that I could spot, describing the sequence of stamps issued in India with Babasaheb as the subject, firstday covers, and panels showing the stamps themselves. The exhibition, I realized, was not just a collection of stamps about the man but a story, gently and yet powerfully told, of how India, which started issuing ‘commemorative’ (one-offs) and ‘definitive’ (a bulk issue, repeated over and over again) stamps for its heroes, especially Mahatma Gandhi, very early after its independence, took quite some time to honour Babasaheb. It was in 1966, a full decade after his death, that the post and telegraph department issued its first commemorative stamp on the leader, a felicity which was repeated in 1973 and on his birth centenary in 1991. But the first definitive stamp for him came only in 2001, on his 110th birth anniversary, during the presidentship of K.R. Narayanan and the prime ministership of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, when the minister in charge of the department was Ram Vilas Paswan, making Babasaheb part of the pantheon of definitive, that is to say ‘regular’, stamps of standard use in India.

Did he suffer by this slow-to-berepaired neglect in the world of dak? No. His stature did not need the assistance of postal print and glue. But the world of postal stationery certainly did suffer as a result. Fortunately, only for a while. As did the universe of popular informal education through the medium of stamps.

As I finished going round the displays, learning about him and about stamps and their supporting literature, and was about to leave, the lean and lone figure I had seen on entering came up to me.

“Please tell me, Sir,” he said, “how we can improve this exhibition?” “Improve? It is beyond any improvement!” I exclaimed. “It is outstanding.” And then I asked, “Are you the curator?” He said he was, indeed, its curator and Dr Vikas Kumar was his name.

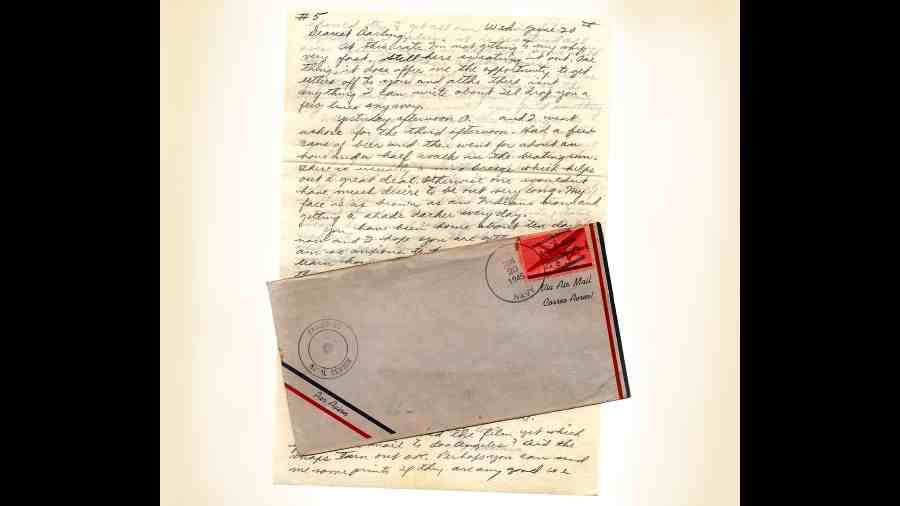

As I came away from that riveting exhibition, I could not but think of the staggering loss to historiography that the unseating of ‘old-style post’ by emails has caused. There is no denying the phenomenal value of laptop correspondence in terms of speed of dispatch, saving of precious paper, cross-disciplinary support to composition by simultaneous referrals to Google and other platforms for fact-checking, spell-checking and data augmentation. But the loss in terms of tactile sharing, of hand-written communications carrying the magic of hand-made errors, hand-corrected, or left uncorrected, of the power of finger-powered writing on real, palpable surfaces, of the almost audible scratching of cleft-nibs or pencil leadheads on those surfaces, is immeasurable. And, along with that, the decay of the value-addition that stamps, postcards and air-letters brought with them.

As an obsessive conservator of ‘real’ letters, very often with their stamp-bearing envelopes, I lament the almost axe-blow suspension of such letters in incoming dak. Now if a letter or postcard comes to me by way of the post, I cherish it like I would a piece of antiquarian rarity. Among my prized possessions are ‘actual’ letters received by me during my five years in West Bengal. These include letters written by men and women for whose intellectual integrity and human veracity I have unbounded regard. Many of them are now no more — Mahasweta Devi of ageless strength, Ashok Mitra of a mind sharp as a razor and a tongue to match, Amlan Datta the gentle questioner, Somnath Hore the incomparable sculptor, P. Lal the calligraphist-author and benefactor-publisher…

Had these amazing human beings emailed me instead of writing ‘proper’ letters, their minds’ signals would have been absorbed by me, even ‘saved’ in a manner of speaking, but not with the ageing immediacy, the fraying magnetism, the dimming audacity, of their written word. I find the way they have addressed the envelopes saying something about them. The use of a ‘Mr’ or ‘Shri’, the latter sometimes with and sometimes without the ‘h’, the addition of ‘extra’ instructions on the envelope’s top left like ‘Personal’, ‘Confidential’, ’Urgent’, ‘To Be Opened by The Addressee’, give the letter the character and feel of a spoken word, a hand’s gesture or a finger’s message.

One can begin an email with ‘Dear so-and-so’ exactly as one might begin a hand-written letter. But the way ‘Dear’ is written and, even more so, the strokes in the concluding ‘Yours…’ are impossible to capture in the cold tappity-tap of a keyboard.

I mentioned some of the precious hand-letters I received in Calcutta. I must also mention some of a different order, but no less valuable for being different. One was written in a lovely, ‘Convent-style’ hand, and began with ‘To The Figurehead of the State’. The writer of that letter on an A4-sized letterhead was giving me a picture-perfect lesson in the provisions of the Constitution that require the Head of a State to act strictly on the aid and advice of the council of ministers. But that was not her intention. She intended to say that the governor was a kind of decoration, an ornament, on the edifice of the State. The affectionate respect contained in it gave me a sense of affinity with the people whose well-being I was enjoined to protect not through the exercise of political clout but a human, familial bonding. Yet another, written in the finest Bangla on an inland letterhead, hurled imprecations on me and wished me an early exit from terra firma for some acts of mine that the writer disapproved of. She signed off with the most witty formulation: Kamana Biswas, meaning Aspiration Confidence and gave her ‘sender’s address’ as Nimtala Ghat Road, on which is located the city’s major crematorium. Delightful! If this letter had come to me by email, it would have conveyed the same message but coming as it did on a signed piece of paper, it became a keepsake as an example of black humour.

The ‘hard-form’ postal system is much debilitated. But it is, I believe, essentially immortal. Like Shelley’s ‘Cloud’, its form may keep changing but it cannot die. But I would like it to do more than ‘not die’. I would like it to preserve human bonds in the pulsations of life, along with the stamps, in their varying colours and values, telling us about persons and places, events and anniversaries, through the compressed idiom of their stories.

It is important that the choice of themes for stamps, the more valuable now for their increasing rarity, be made with great sensitivity and objectivity. For this, the processes of theme-selection need the guidance of dispassionate historians and discriminating artists. The road of India’s historiography is going to be traversed by new and undreamt of vehicles. But the slow yet steady trundle of its philatelic-cart must never go off that track.