The past, present and future are often used in quick succession, inferring a continuity that determines not merely time and space but our entire existence. The three words, although interconnected, do not evoke the same feelings. The past is a concluded occurrence about which nothing can be done. The present is a current state that is tinged with an inevitability that could be pleasurable or otherwise. The future is a possibility, an aspiration shrouded in uncertainty. Our everyday lives exist in the intersection of these time states. Therefore, although we live in the present, our mind’s mystical ability to move across time configures our present moment.In this constant state of shift, we discover that none of these time determinants is what we think it is. They are always alive and morphing in ways that are least expected.

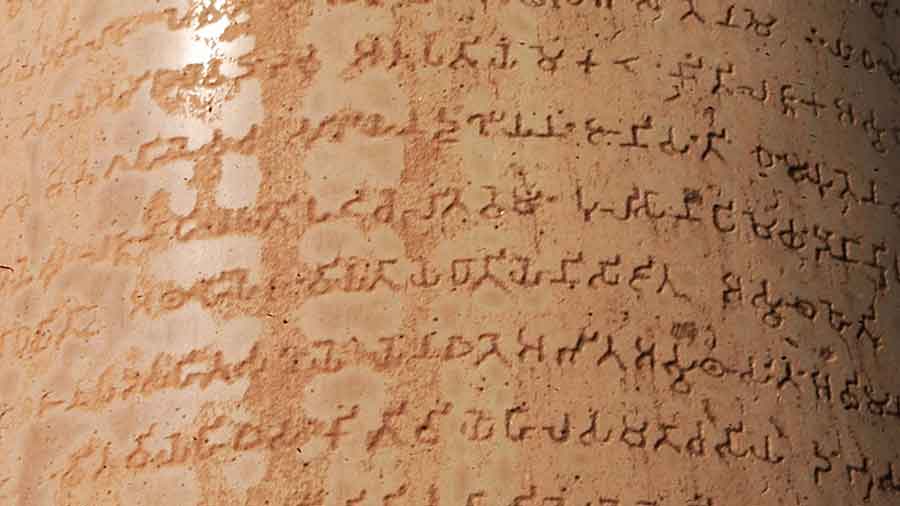

These thoughts came to my mind when I worked on King Ashoka’s edicts: words of a ruler etched on rocks and pillars more than two thousand years ago. My only relationship with the edicts had been a few lines in my high school history textbook. But, as I explored the various themes that Ashoka ruminated about and advised and insisted upon, I began to wonder how I was receiving them. In other words, what meaning was I drawing from the words of an ancient monarch? And the follow-up question: why was I drawing those meanings for myself?

The past is not a collection of done and dusted events. The physical events have ended but various memory threads remain. The moment I use the word, ‘memory’, we enter the realm of the living. Looking into the past is always an act by and for the present. The reasons may or may not be obvious; nevertheless, the story always begins from a need that originates in the ‘today’. We dive into the past in our search for reason, to understand, grapple with our lives. The question of which past or what in the past we are in search of is also probably pre-confirmed. From the time thought appeared in our minds, names, places, situations and moments of the past were seeded. Hence, when we turn the clock back, we gravitate towards specific individuals or time periods.

My seeking of Ashoka was also probably pre-designed. The image of the ideal king was instilled in me from childhood, the gentle elegance of the Lion Capital and the drama of his sudden metamorphoses contributing to this need. But why now? I am struggling to make sense of today’s India where violence has been normalised. We are numb to death. Bodies float on rivers, people are beaten up, hacked and maimed, but we remain bystanders, satisfied with social media outrage. I wanted to make sense of it all and find a pathway through this dark phase. During one such conversation, Gopalkrishna Gandhi suggested that I read the edicts again. A suggestion that emerged from his memory reservoir.

There is one more mental operation we indulge in. We sieve the past for stories that suit our present needs and reject those that make us uncomfortable. The meanings we draw need to help us feel comfortable and justify the present even if it means condoning violence or mourning the terrible present as a result of a failed past, allowing us to disown any responsibility for the current condition. The way many turn a blind eye to the violence unleashed on minorities is an example of how past action by an unconnected individual can be used to convince us that this retribution is essential. When individuals with caste privilege conveniently place the burden of casteism on their forefathers and refuse to see their own participation, they use the past to cleanse themselves. Ashoka was, no doubt, an extraordinary human being. Despite living in a time when any display of vulnerability by a king would have been considered a weakness, he expressed his internal conflicts and doubts in public. All in the hope that a better society could be constructed. But that was not all he was doing. He was prescriptive, forceful and, like all of us, selective about the past he wanted to depict. He was telling his subjects that the reformed Ashoka was creating a compassionate society, one that never existed before him. In that sense, he too was monochromatic in the view he wished to present. He was a politician after all!

I will not take on the Machiavellian misrepresentations of the past that have become a political tool today because there can be no discussion with those who deliberately perpetuate fraudulent narratives. But there needs to be a conversation with those who have always seen or been shown one angle of the past due to social insularity. They find any other perspective offensive or just refuse to see it.

The past and present are not a sequential line of causative events. Instead, they are bundles of happenings in all directions with contradicting impacts. Acceptance, rejection, harm, love, sorrow and happiness coexist. This means that something that benefited me harmed someone else, an event was beautiful and ugly, a monument an aesthetic achievement and a result of unchallenged oppression. Our innate nature to place any dialogue into a binary structure makes it impossible to initiate a nuanced or, for that matter, sane conversation in this regard. As a species, we have a need to categorise and reconcile all information we receive into two categories. One that we will embrace and the other that we will trivialise. This means we prefer not to deal with the in-betweens, the grey. For example, the possibility that Tipu Sultan was both kind and violent, that Gandhi was compassionate yet carried caste blinders, Ambedkar was brilliant but, at times, wrong, and Ashoka himself both caring and authoritarian.

If we want to change the way we look at the past, our understanding of ourselves has to alter. We are not a benign, consistent species. Our every thought is loaded with choreographed habits and memories, and every action cross-wired with the need to self-preserve and public action. This makes us incapable of altruism in the absolute sense of the term. It may be impossible to disentangle ourselves from this spider’s web, but we can remain aware and vigilant. Then the reason we look to the past and the way we receive from the past will change. We will not see the need to erase chapters from textbooks or murder individuals who shine a dark light on our heroes. No king will be a paragon of virtue, no religion a pure creation of god, and no leader a saviour of all.

Such a reimagination will make us more empathetic and cohesive. None of us will sit on a higher pedestal claiming greater knowledge, faith or community. The ever-elusives — equality, justice and fraternity — will be nearer our reach. We may not ever achieve a utopian state, but we will stabilise at a taut equilibrium where we can question without violence and listen without judgment. Then the past will not be a crutch, the present not inevitable, and the future a comprehensible possibility. But what about the truth?

The truth lies in our honesty.

(T.M. Krishna is a leading Indian musician and a prominent public intellectual)