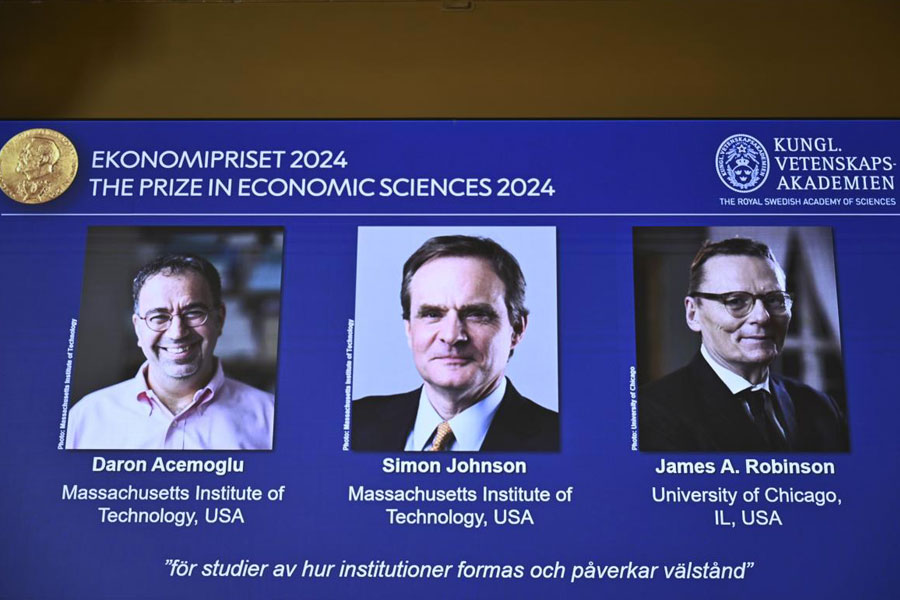

Institutions play a fundamental role in creating variances in economic development around the world. This is the crux of the research done by the three economists, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson, who were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics this year. In its press release, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences explained the significance of the work of Mr Acemoglu, Mr Johnson and

Mr Robinson by saying that the laureates’ research help understand why societies with poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better. The laureates’ empirical and theoretical model is based on a distinction they make between “inclusive” and “extractive” institutions. Inclusive institutions encourage people’s participation in economic activities with proper use of their talents and skills and, thus, ensure a country’s prosperity by incentivising them to excel. Extractive ones, on the other hand, create disincentives for the people by wasting or ignoring human input and the grabbing of resources, like labour or minerals, by those in power and their cronies, thereby slamming the brakes on growth.

This hypothesis does have an appeal to common sense as repressive regimes characterised by extractive institutions tend to have poorer economic scorecards than their liberal counterparts comprising inclusive institutions. These findings have special implications for countries like India. For instance, the recent trend of millionaires leaving India — 4,300 of them are expected to move out of the country this year according to a report — can be explained by this institution-based narrative at a time when there are serious allegations of tax terrorism against Indian authorities. The theory of the laureates can also come in handy to predict an impending economic crisis in Bangladesh where the rule of law has deteriorated significantly since the fall of the Sheikh Hasina Wazed government in August.

The laureates referred to colonial history to build their case and linked the current differences in prosperity in former European colonies — rich countries like the United States of America and Australia and poor ones like Nigeria and Pakistan — to the quality of institutions. The former colonies that eventually became rich were the ones where the colonialists created inclusive political and economic systems or strong property rights. The poorer ones had weak property rights as the purpose was to exploit the indigenous population and extract resources to benefit the colonists. The choice of institutions by the colonists, the three economists suggest, was linked to the mortality rate of settlers in the colonies. The settlers created extractive institutions in regions with high mortality rates. The colonialists, however, built inclusive institutions in countries like the US as their chances of survival were higher there.

The laureates’ hypothesis, however, is not free of potential limitations. For example, the settlers also brought with them technical know-how and human capital that played a key role in producing divergent economic scorecards in these countries. The impact of such ‘imports’ on not only a country’s economic performance but also global inequality merits introspection. Hopefully, democracies like India would take note of this research and begin the process of fortifying institutions to spur growth.