One word that has gone missing from our Bengali vocabulary is “palpitation”. I say Bengali because the familiarity with which it was used in Bengali middle-class homes made it lose its foreignness. Perhaps the popularity of the word was owing to the fact that the condition it represented was a recurrent one that seemed to affect a large number of Bengalis of a certain age. Any kind of excitement, major or minor, happy or sad, near or distant, could cause palpitation. I was raised by grandmothers and grandaunts, and grandfathers and granduncles, who would often clutch their hearts following an incident — a long-distance call would count as one, too — and make the pronouncement: “Amar toh palpitation shuru hoye gelo!”

Of course, sometimes it could be caused by an actual severe heart condition. But when it was not, it served a number of purposes. A: It summed up the peculiar Bengali mix of nervousness and collapse that often meets any prospect of change, even a small one. B: It was a very expressive word. It was onomatopoeic and seemed to reproduce the thudding of the heart, the specific condition it described. C: There was something vital and comic about the word, especially when the reaction far exceeded the cause of agitation. For example, I imagine Lalmohanbabu, Satyajit Ray’s classic caricature of the Bengali bhadralok, suffering several palpitations as he stood among the sands of Rajasthan contemplating a camel, which was towering above him. He would have to ride it. One of our female relatives would react with heavy palpitation every time her husband returned home at night, smelling of alcohol underneath his paan breath. We would know well the look of sad resignation and prolonged agony on her face that would precede the palpitation. The palpitation could sometimes be followed by swooning, but she would be perfectly all right in the morning. She lived long. D: The word adequately represented a state of intense agitation, yet, because it was expressed as a very specific physical reaction, which would eventually subside, its experience did not seem unmanageable.

It is for this last reason that I mourn the departure of the word from our vocabulary most. As I do of “unsmart”, another word that was English in origin but became absolutely Bengali in its meaning. Or “cadaverous”: it came to mean hideous, but not in a pale, corpse-like way. In-laws, who tortured a woman and therefore were obviously robust in some way, could be cadaverous.

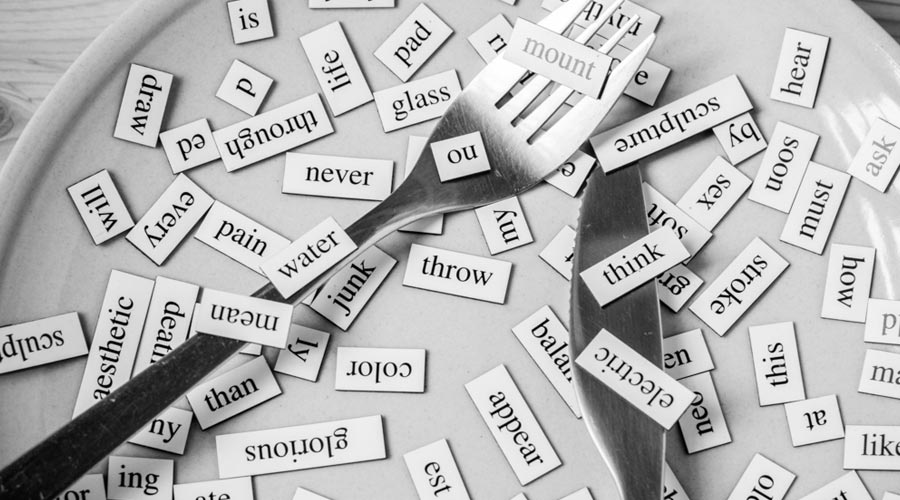

Now the English words that are a part of Bengali are overwhelming in number and are mostly about consuming, in more than one way, pertaining to buying, shopping, technology or eating, or are aspirational, and often appear as proper nouns, invented to suit products. They constitute a new hybrid language, a wild growth of words that are meant to evoke romance and global north landscapes, but can end up being grotesque and even violent.

The words, “stress” and “anxiety”, are also part of this new vocabulary. And one does not fool around with stress. We experience it not as one long-distance phone call, because distance itself has been eliminated. Especially in a world devastated by the pandemic, stress is present like the virus, potentially everywhere. Or like climate change. It cannot be contained. It cannot be controlled. We are in it. We have been in it for quite some time. It changes everything.

Something like a palpitation is a very inadequate response to such a phenomenon. It feels naïve, ridiculous, feeble and lacklustre. If it thrives, it does so in little corners. One of my friends says she suffers from palpitation every time she gets late for work. I do not. My mind is so crowded all the time that I hardly hear anything. The only noise that I cannot escape is that of my mobile phone screaming. Or even beeping.

On Thursday, as the state election results were coming in, that was a terrifying sound. It made for a lot of stress.