The Covid-19 pandemic could be seen as an experiment to test democracy’s responsiveness towards, and its ability to overcome, widespread sufferings through reasoned public opinion and elections. Elections have taken place amidst the pandemic, be it in the United States of America or in Bihar. Do these elections in the midst of the pandemic sufficiently reflect people’s anger, political discontent and, therefore, the sensitivity of democracy?

Comparisons of electoral outcomes between the US and Bihar might appear to be disproportionate in terms of State capacity to address the crisis. Nonetheless, the results, be they in the US or those in Bihar, raise more questions than answers about democracy’s sensibility in the hour of crisis. Institutions devoted to the safeguarding of democracy by upholding the rights of the people and fostering the scientific temperament lie weakened, their autonomy diluted. Partisan divisions in the federal structure are now explicit. An independent and progressive judiciary is allegedly not the norm today but an exception. Institutional integrity and a responsible media are rare. The results — the dissemination of conspiracy theories and unscientific claims and the glorification of hatred — have been along expected lines.

Electoral issues in the US vary from those in Bihar. The debate on healthcare dominated the US polls, while caste and communal politics determined the Bihar elections. Nonetheless, the pandemic led to some shared experiences. The US recorded massive infections and job losses and thousands of deaths. Bihar, one of India’s poorest states that sends 7.5 million migrant workers to other states, was witness to unprecedented sufferings of migrants who were forced to undertake perilous journeys on highways and along railway tracks without any aid in terms of food, transportation or medicine. Therefore, many of the experiences of voters in Bihar and in the US — deaths, job losses — were common.

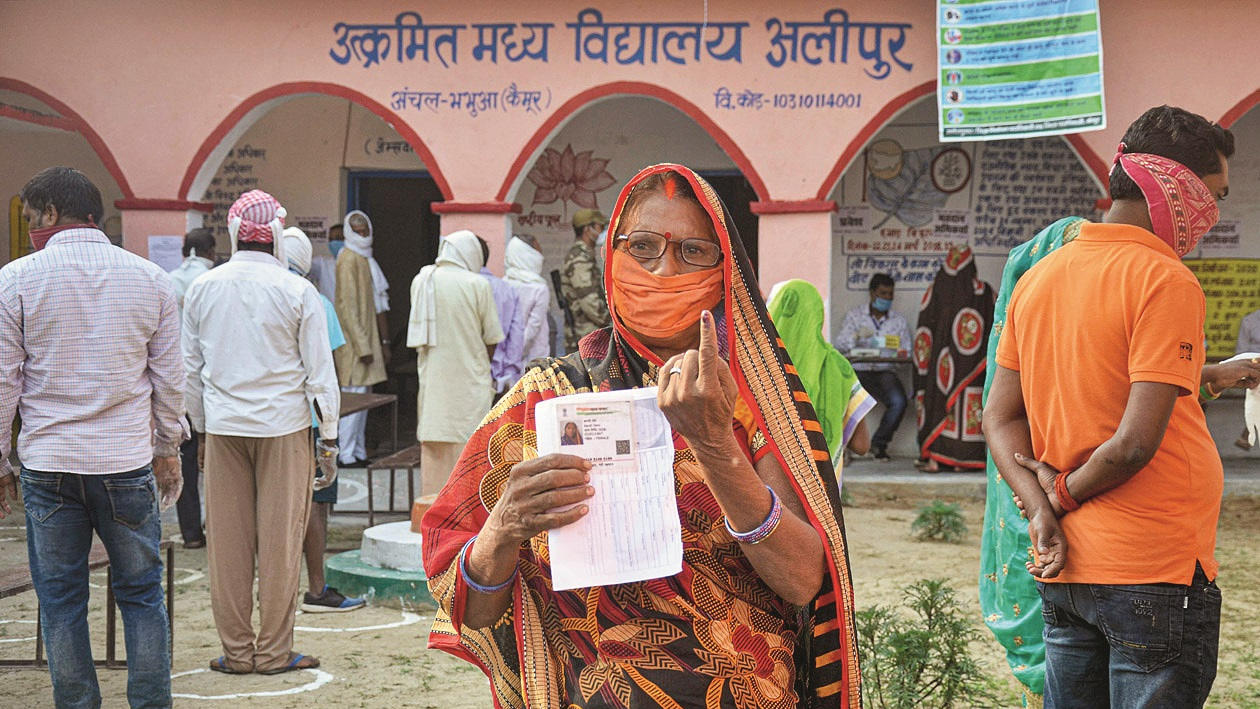

The turnout in the US rose to 66.8 per cent from 60.1 per cent in 2016. Bihar’s turnout increased to 57.1 per cent from 56.7 per cent in 2015. Can it be argued that the figures suggest the robust health of democracy in the two nations? If this were the case, the turnouts would have been far higher since electoral participation is easier than what it was earlier. Strikingly, the results did not indicate that the voters had overwhelmingly rejected the incumbent governments in spite of their mismanagement of the pandemic. About 37.1 per cent of the 42 million popular voters in Bihar trusted the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance. In the US, the Democrats won the presidency with 51.1 per cent of the popular vote but the outgoing Republican president also received 47.2 per cent of the vote. If only two per cent of the popular vote had swung in favour of Republicans, Donald Trump would have been re-elected even though his governance in the time of a pandemic was a spectacular failure.

It is evident that both in the US and Bihar, democracy has not responded in the manner one would expect it to. The electoral verdict went in favour of the incumbent government in Bihar, while in the US, the serving president lost narrowly despite the fact that both administrations have grossly mismanaged the Covid-19 pandemic. This goes to show that the problem does not lie with the form of democracy; it lies in the content with which democracies are functioning today.