Language riots occur for many reasons — love, hate, resistance, cultural assertion, economics, politics, ideology and more. Participants in the December 2023 language riots in Bengaluru were pro-Kannada, but not against any other language.

It is not like Tamil Nadu resisting Hindi, for instance; that was an assertion of the Dravidian identity, as much ideological as it was cultural. But even the love for a mother tongue, as apparently in Bengaluru, is not simple. Studies of certain major cities indicate that an outcome of urban migration has been the shifts in linguistic balance throughout India. Language hierarchies often turn on economics, so it would be natural to ask whether native speakers in a city with a bustling information technology sector are agitated when people from other states join well-paid jobs. The linguistic variety among migrants may be why the pro-Kannada sentiments do not target a particular language. Yet these riots are a reminder that mobility also demands governmental thinking about modes of integration and cultural enrichment which, at its best, can change fault lines into bridges.

That has not been the case so far. Many languages might be converging in Bengaluru, but it is the only major city in the South where the use of Hindi has doubled — from 3% to 6% in the last two decades for which the census is available. Yet Kannada has grown over the same period. So it may be both love and assertion of identity that prompted the language unrest, although the lack of 2021 census data hobbles inferences. Hatred was more obvious in Gujarat in 2018, when some Hindi-speaking migrants from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh were forced to leave, as also earlier from Mumbai. That is strange for a cosmopolitan centre, but Gujarati and Marathi languages are shrinking, as evidence from Surat, Ahmedabad, Mumbai and Thane has shown.

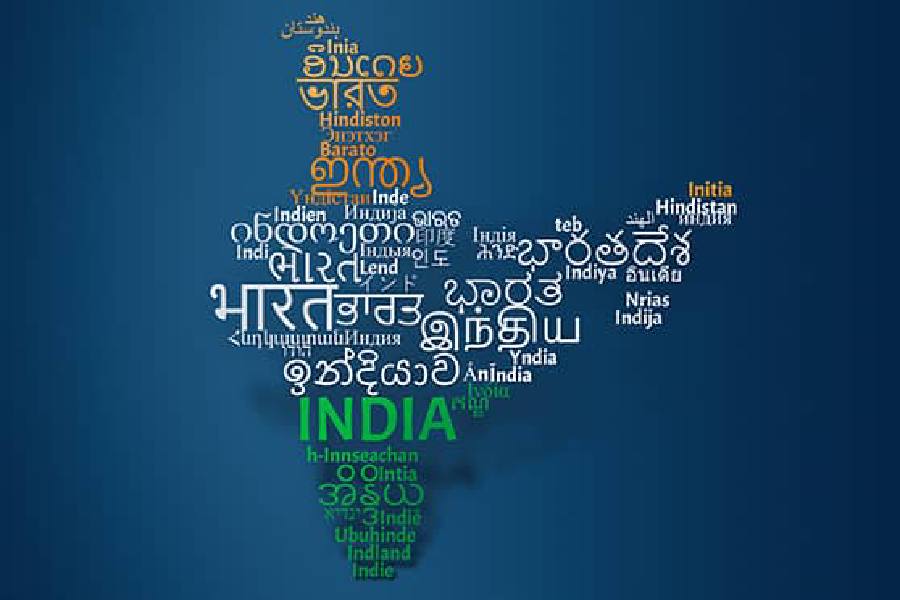

Hindi has become the greatest focus of anger. Many languages meet and mingle in the Indian states: Indians are bilingual, trilingual and can even know four languages without noticing it. But Hindi, the official language, is also growing the fastest; because of its presence throughout the northern belt, it is associated with political dominance. The resentment towards it is part political — sometimes ideological with the present regime — and part an assertion of cultural and linguistic identity, a desire to keep mother tongues afloat. Language conflicts resulting from urban migration, however, are visible; much of the clash of languages remains invisible. Children from far-flung regions or tribal communities, for instance, often do not follow lessons in school even if they are taught in the major language of the state they inhabit. There are no riots. Yet this is as grave an issue as linguistic shifts through urban migration. In this country of multiple languages, if fault lines are to be changed to bridges, much care would be needed to alleviate the linguistic alienation of those whose mother tongue is not a state language at all.