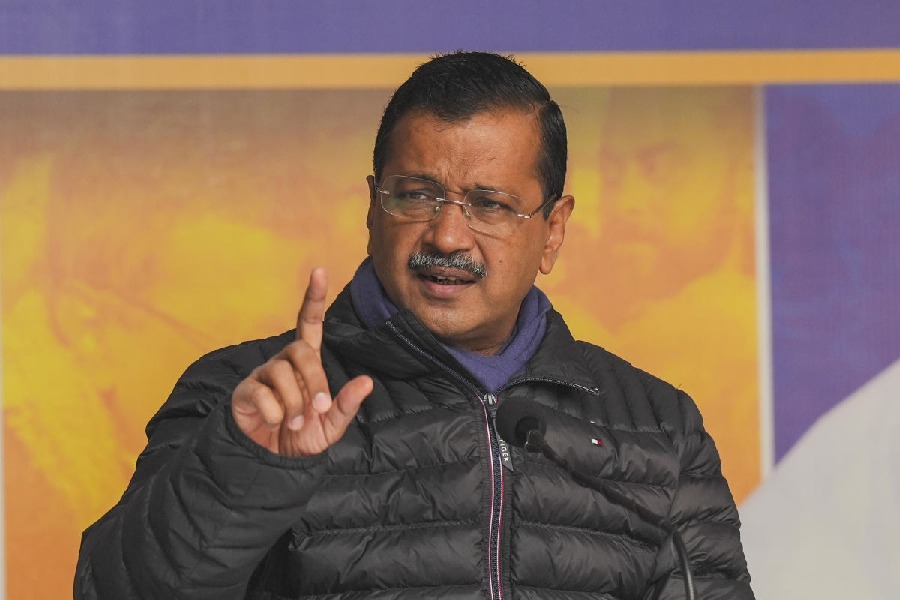

The Trinamool Congress’s decision to not attend the meeting of the INDIA bloc at the chamber of the Congress president, Mallikarjun Kharge, is meant to convey a message. The message is that Bengal’s ruling party is not keen to be part of the Opposition’s efforts to corner the Narendra Modi government in Parliament over the indictment of the businessman, Gautam Adani, in the United States of America. This distancing between the TMC and the Opposition needs to be looked at in light of a recent — hushed — exchange between two leaders of the TMC and the Congress, respectively. Apparently, after the publication of the assembly poll results in Maharashtra and the by-poll results in Bengal — the Congress was trounced in the former while the TMC emerged triumphant in the latter — a leader from Mamata Banerjee’s party was urged by a Congressman to raise charges against Mr Adani in the winter session of Parliament. But the TMC responded by saying that corruption is no longer a productive electoral issue.

The TMC’s belief merits examination. Corruption has often led to changes in political regimes in India. The Bofors scam had tainted Rajiv Gandhi’s government; several charges of corruption dented the United Progressive Alliance II’s hopes of returning to power; more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party lost Karnataka because of the public perception that the state unit had sticky fingers. But the reverse holds true as well. The TMC, allegedly neck-deep in corruption, continues to win elections in Bengal. Several campaigns in which the Opposition has hurled charges of corruption against Mr Modi have failed to reverberate with the voters. Could it be that Indians have become inured to corruption as an electoral issue? India had occupied a lowly 93 rank out of 180 countries in the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index. The weaponisation of investigative agencies under Mr Modi’s watch has led to anti-corruption drives being patently discriminatory. The taming of the media has also prevented adequate investigations and exposés of fraudulent activities, especially of those close to the powers that be. Together, all these have resulted in heightened public cynicism. Little wonder then that two-third of the respondents of a Pew research survey held politicians to be incorrigibly corrupt. The all-pervasive sway of corruption — from everyday experiences to careers in public life — has led to the crystallization of a collective despair that has made the voter indifferent to charges of political amorality during elections.