The pandemic is truly a global moment even if it may well mark the end of globalization, or at least some of its prominent features as we have known it. The responses to this global moment also underscore the persistence of diversity notwithstanding the three-decade-plus drum beat of globalization. This range is expressed at one end to our west by war-torn Syria, Afghanistan and other nations where the UN secretary-general’s appeal for ceasefires has had little or no impact in spite of the dangers posed by the pandemic.

At the other end to our east, in Southeast and Northeast Asia, we have approaches to this pandemic that derive much from the experience gained from dealing with the MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak of 2015 or that of SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome)in 2003. Flattening the infection curve here has meant supplementing medical and public health measures with high-technology tracking and surveillance systems, deploying big data analysis by integrating a range of platforms, from immigration, health, credit cards and mobile phone usage to CCTV footage. All these government measures are based to an extent on citizen compliance with government directive that is not easily found elsewhere.

Thus, behind the range of national responses that we witness is the larger question of the nature of polities and the relationship between State and civil society.

We get another view of a deeply contested State-civil society interface during a pandemic in colonial India in the late 19th century. This was a dramatic moment when plague had affected large parts of the country and, in particular, western India. A large part of the drama focused on Poona, home of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, charting a course that would be followed by subsequent generations of nationalists. The details of the drama are important to understand this late-19th-century collision of opposing narratives of history, nationalism, epidemics and State-civil society relations.

The year, 1896, had seen the failure of the monsoons which heralded crop failures in large parts of the Bombay Presidency. This was also the year which saw Tilak embarking on another venture with far-reaching consequences — a festival to commemorate the birth of Shivaji. For Tilak, the revival of Shivaji was important because loss of freedom had meant no less than the fading — almost to extinction — of the memory of Shivaji and Maratha history: commemorating the Maratha king was, therefore, akin to regaining agency and that was the first step towards full freedom.

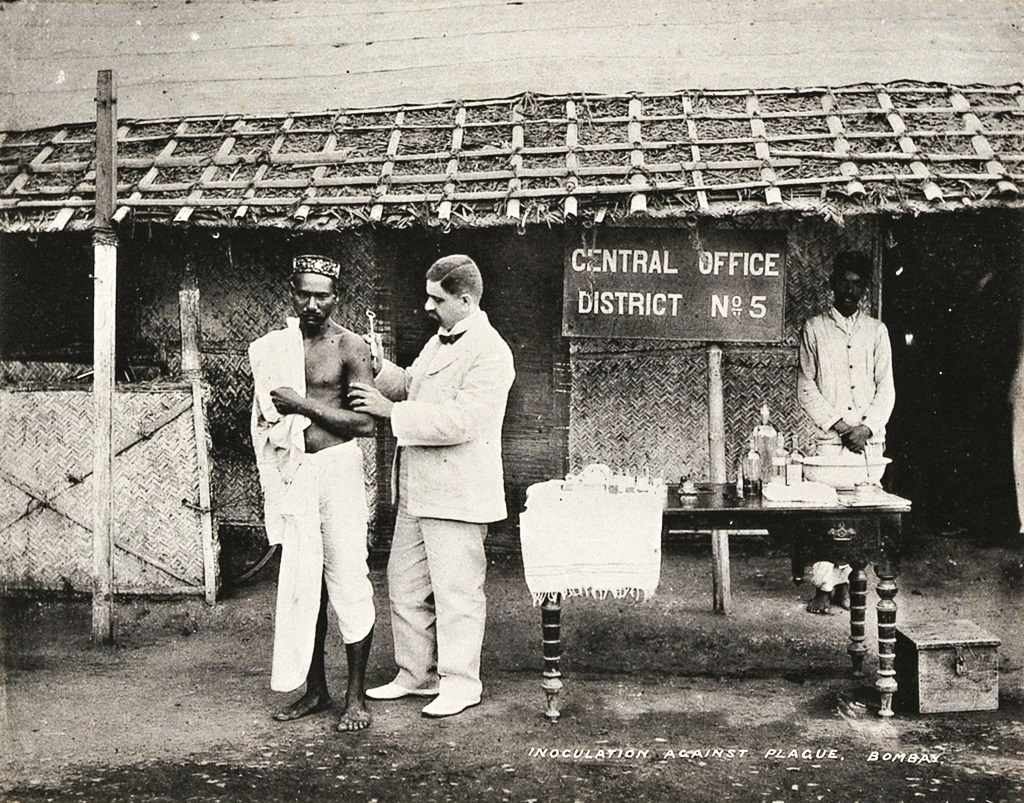

By the end of the year, other ominous developments were in motion with the detection of the first cases of the plague in the port cities of Bombay and Karachi. These cities were both transit points and incubators and by early 1897, the death toll all over western India was mounting. As the second Shivaji festival approached, the government’s anti-plague measures in Poona had acquired prominence and were often accompanied by strong measures by executive officers determined to clean up plague hotspots. Plague operations in Poona were headed by a British officer, W.C. Rand, who called in troops to help fumigate and clean those houses in which infection was detected or suspected. Those infected were lodged in special isolation camps outside the city. The utility of these measures was increasingly being questioned as the death toll continued to grow alongside resentment at the heavy-handed measures used by Rand. Much of the intensity of the government’s anti-plague measures was derived from the fear of the plague spreading to Britain and Europe from India.

The first Shivaji festival had been held in April, 1896 — April is the month of Shivaji’s birth. The second festival was moved to June — the month he had been crowned in 1674. The change was, however, significant in a contemporary sense too. It meant that the Shivaji festival would now fall just a few days before an Empire-wide event — the Diamond Jubilee, or the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s coronation.

The Diamond Jubilee celebrations in different parts of India was the final ingredient to the explosive cocktail brewing, adding potency to the brew of famine, plague and resentment against a high-handed colonial government. Clearly, given the situation in large parts of the country, such celebrations were insensitive — indeed, only a few months ago, the Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897, recently invoked again to address the coronavirus pandemic, was framed as a package of steps to empower local officials to enforce strict measures to deal with the plague.

The Shivaji festival in Poona also featured a lecture titled “The Killing of Afzal Khan”. This was a seminal event in Maratha history in which the Bijapur general, Afzal Khan, was killed by Shivaji during a one-on-one meeting. The lecture devoted itself to addressing the question whether the killing was an act of treachery. Tilak had presided over the lecture. In his remarks, later printed in his newspaper, he said Shivaji was not guilty because he acted with benevolent intentions for the good of others: “Do not circumscribe your vision like a frog in a well; get out of the penal code and enter the atmosphere of the Bhagvad Gita.”

A few days later — on June 22 — was the Queen Victoria Jubilee night. The Bombay governor’s Poona residence — Ganeshkhind — was the venue of a grand reception. Amongst those attending was the Poona plague officer, Rand. He was assassinated along with another British officer as they left.

The rest, as they say, is history. The three Chapekar brothers — the conspirators and the assassins — were apprehended and sentenced to death. Tilak was also arrested and sentenced to 18 months rigorous imprisonment — his lecture at the Shivaji festival had motivated the assassins, argued the prosecution. The jury was split six to three between Europeans and Indians. Tilak returned from jail with a nationwide reputation — he was spontaneously known henceforth as Lokmanya. The issue was not so much the plague alone but of the interface between the actions of a colonial government and its subjects.

Returning to our own times and to the global moment the coronavirus has evoked: the virus’s transmission is clearly a parallel process to the forces of globalization. But the connection itself is not new. At the end of the 19th century, the plague reached Poona from Bombay but it had emerged in Hong Kong and a range of Empire-wide forces were evidently at play. But such global moments have even older histories. A celebrated French historian, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, had spoken in the 1970s about “the unification of the globe by disease” between the 14th and the 17th centuries. Disease itself had been around from much earlier but the geography of epidemics was limited in their impact by a kind of ‘cordon sanitaire’ that was broken with greater long-distance trade, travel, the movement of armies and so on. A ‘community of disease’ was, therefore, created. Ladurie’s perspective, however, also was that “unification by disease” as “the evil concomitant of expansion and trade” has “lost its power in our times to drastically alter the history of mankind”. Let us see if this judgment survives the Covid-19 pandemic.