Truth, as the adage goes, can be stranger than fiction. It has been reported that days before Vladimir Putin’s troops were to begin their assault on Ukraine, something strange took place in the German town of Lützen: the town’s officials accorded ‘landmark status’ to a Soviet-era memorial that traced its roots back to the Second World War, commemorating, on one side of the structure, the death of some Russian prisoners at the hands of German forces. The novelty of this commemoration becomes clear when one takes into account the geostrategic dynamics of both the past and the present. The erstwhile Soviet Union and Germany were bitter opponents during the War; even today, Germany has, quite correctly, sided with Ukraine, Russia’s current adversary. Yet, most Germans have had little qualms about seemingly upending patriotism and geographical borders by taking on the task of protecting — nourishing — thousands of Soviet monuments and war memorabilia that glorify their opponents. Their objective is altruistic. Germany wants to preserve and learn from one of the most shameful chapters in German history — the years of Nazi occupation and atrocities —by turning memory and attendant guilt into moral compasses for the future.

Reconciliation can be an important element in the pursuit of justice. The employment of guilt is central to these projects to imbibe bitter lessons from the past so as not to commit the same blunders in the future. Germany is not the only nation to be experimenting with this principle of self-abnegation. South Africa, a society that unveiled the horror of Apartheid to the world, constituted the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with an eye on healing deep wounds and achieving restorative justice. India, a witness to the trauma of Partition, has not been averse to this kind of amelioration either. Amritsar’s Partition Museum is a singular attempt at not only collating diverse artefacts related to that time of tumult but also using the material as a form of public education so that the fault lines — they continue to simmer — can be confronted.

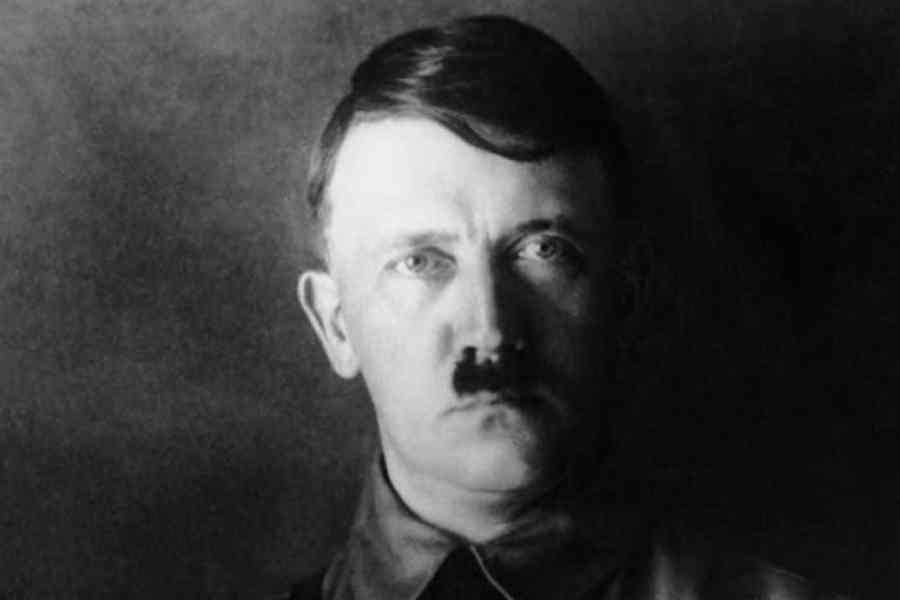

But a culture of contrition, if it is imposed externally, can be a double-edged sword. It must be remembered that the disproportionate burden of shame and reparations that Germany was made to bear after the end of the First World War had been instrumental in the rise of the ogre called Nazism. The challenge, therefore, is to ensure that penance is collective and earnest. This is a formidable goal. Even in Germany, which has been so sincere in its attempts at acknowledging its complicities in crimes against humanity, it has been noted that reconciliation has led to revealing forms of complacency: many young Germans, content with expressing remorse at their past, have turned indifferent to excesses of the present. The ascendancy of shrill nationalism has brought with it peculiar forms of resistance as well. Reconciliation initiatives in other parts of the world, including India, must be mindful of these emerging conditions. The possession of conscience is not enough for a society to learn from its past mistakes. Conscience needs its own crutches, including commemorative installations and the ability to view them without prejudice.