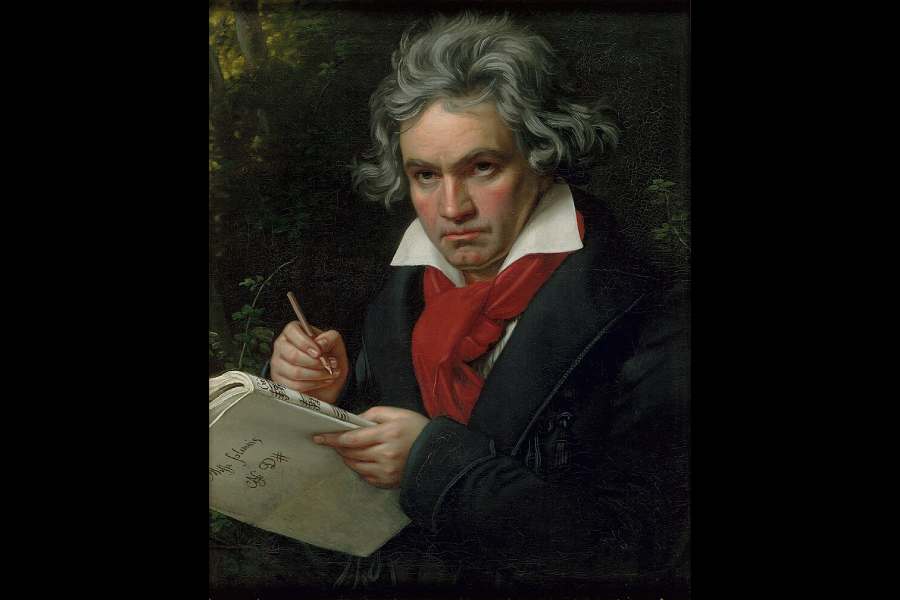

The Ninth Symphony has not lost its power 200 years after its first performance. The search for joy emerging from dark despair is symbolic of the glorious assertion of Beethoven’s triumph over his deafness. The need to express what he felt lay within him, or only ‘Art’, he said, held him back from suicide. His ability to go on composing great music in spite of growing deafness from his 20s was almost miraculous. But it led to depression and a gradual withdrawal from society. It is as though the urge to create can overcome afflictions that target the senses or abilities the artist needs most. Milton, like Beethoven, arrived at his own understanding of the place of blindness in his life, although in his case it was through god: he accepted that they also serve god who only stand and wait. But he was not the standing-around kind. He started the strenuous labour of composing "Paradise Lost" after he had lost his eyesight.

The recent discovery of huge amounts of lead in the preserved locks of Beethoven indicates the probable source of his deafness and other exhausting ailments for which he had desperately tried to find the cause. It is tragic that the cheap wine he believed to be good for him had lead in it, as did his medicines. The times were adverse: Milton’s use of strange remedies did not change his blindness but gave him gout instead. Centuries later, Borges, going blind from an inherited illness, turned to writing poetry, because it was easier to put down with impaired vision. Death alone could stop creation. Keats could not escape tuberculosis, neither could Anne and Emily Brontë; Mozart died early possibly as a consequence of an childhood attack of rheumatic fever. Goya started feeling dizzy with headaches; alarmingly, he began to lose mobility in his right arm. He treated himself with mercury, while his paints contained lead, both dangerous. His Black Paintings seem to represent the dark places to which his creativity was taking him in his hour of pain. But creating did not stop. For Monet, who continued painting his water lilies as he gradually lost his vision, the times were kinder. He did get a pair of spectacles that helped somewhat. Painting became Frida Kahlo’s life only after she recovered from an almost fatal accident: her chronic pain seeped into her compositions. Would van Gogh’s Starry Nights have been quite the same had his mind been steadily earthbound all the time? Or would Woolf have taken her readers on unique journeys had she not been occasionally dislocated from the familiar world?

Illness is not a condition for art, but affliction seems to push artists to a kind of superhuman efflorescence of creativity to defeat it. Art may be beautiful or terrible, but it is always pitiless; as Beethoven said, it would be unthinkable to leave the world without bringing forth all that lies within.