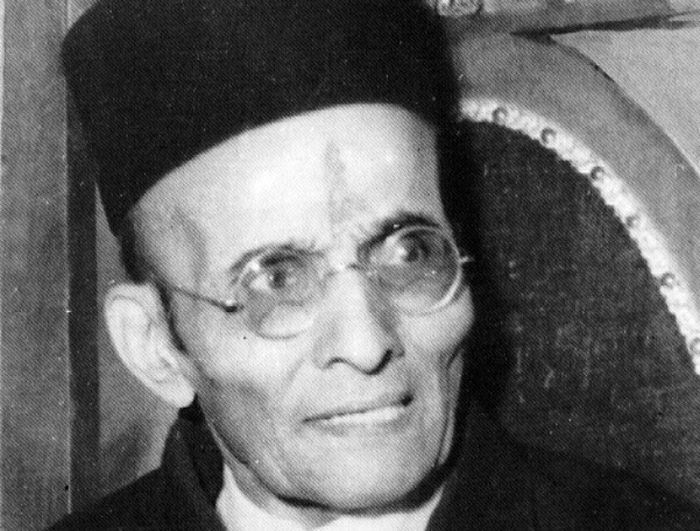

National honour should, under ideal circumstances, be bestowed upon distinguished citizens on the basis of the unanimity of choice. However, when it comes to the Bharat Ratna — the nation’s highest civilian award — the dark art of politics has ensured that such consensus remains elusive. As a result, the India of Old had witnessed the filing of legal petitions protesting the government’s decision to confer the Bharat Ratna on some individuals. It now appears that New India would not be spared of such contentious choices. In its manifesto for the forthcoming assembly elections in Maharashtra, the Bharatiya Janata Party, which is seeking to return to power in the state, has proposed the name of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar as an awardee. The BJP’s decision is undoubtedly informed by the compulsions of competitive populism. Savarkar, born in Maharashtra, could help sway public sentiments during the electoral test. There is, however, that little matter of sullying the glory of the ratna with the stain of patronage. The BJP, even though it claims to be a party with a difference, is, evidently, not bothered by such delicate ethical dilemmas. It remains intent, much like its principal political rival, on using the Bharat Ratna to meet express political goals.

But political patronage is only a minor problem in this context. The BJP’s proposal is bound to make every Indian wedded to the principle of pluralism wonder whether Savarkar would be a deserving recipient. Savarkar’s legacy remains unambiguously chequered, even though the prime minister has now decreed that his values are synonymous with nationalism. During his incarceration in Andaman’s notorious Cellular Jail, he presented not one but two petitions of clemency, pledging his loyalty to the British government. A number of Savarkar’s fellow inmates — among them were Bengali revolutionaries like Ullaskar Dutta — chose to endure the merciless regime without pleading for mercy. These patriots have a greater claim on the Bharat Ratna. Moreover, does not Savarkar’s vision of an exclusivist, majoritarian republic — he minted Hindutva as a political philosophy — make him a dubious contender for the highest civilian honour of a nation that prides itself on being an accommodating democracy?