Freedoms of speech, expression, assembly and trade are fundamental rights of every Indian citizen. Despite this solemn constitutional guarantee, an innocuous slogan, ‘Pakistan zindabad, Hindustan zindabad’, has led to a young citizen being charged with sedition; protesters at Shaheen Bagh have been frequently termed ‘anti-national’ despite exercising their rights peacefully. Traders in Kashmir have been effectively denied their right to trade for nearly half of last year with the state being in various degrees of lockdown. It might be tempting to simply blame the authoritarian times we live in for this state of affairs. While this may be correct, it would be just as myopic. Organiser, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh mouthpiece, was banned by Jawaharlal Nehru for publishing objectionable material threatening public order in 1950; the left-leaning publication, Cross Roads, met the same fate for criticizing India’s foreign policy; closer to the present, Aseem Trivedi was charged with sedition for showing Parliament in the shape of a commode during Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption movement.

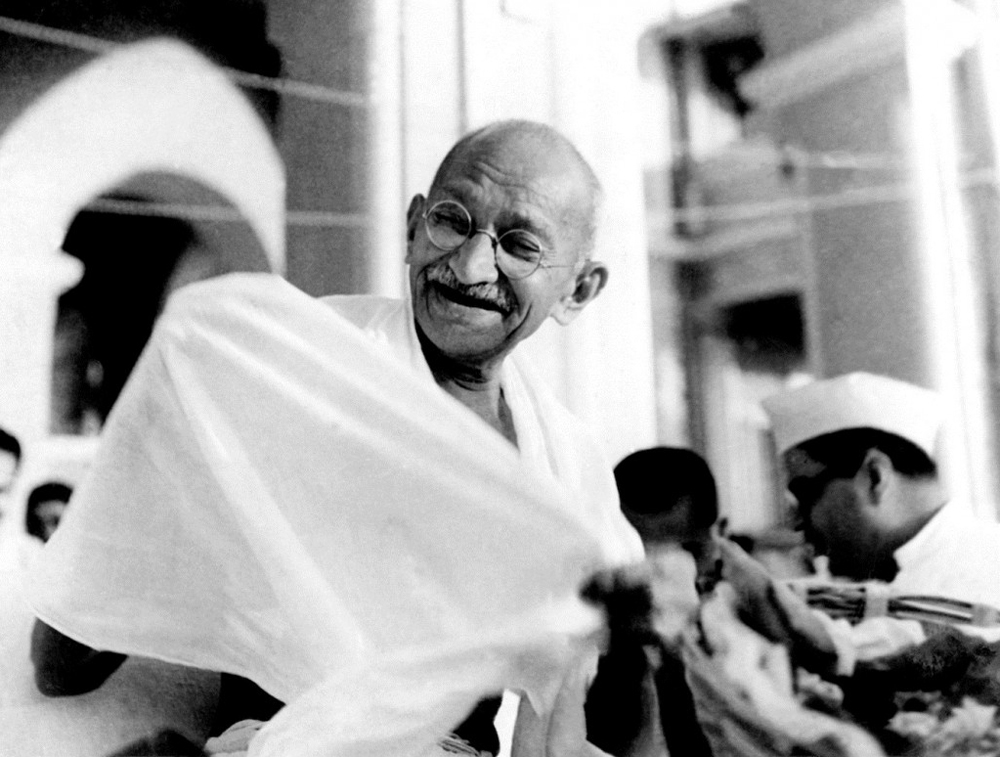

Historically, governments in India have had a testy relationship with the fundamental rights of citizens. This is despite being obligated by the Constitution to respect them. Mahatma Gandhi had foreseen this. In Hind Swaraj, he had warned that if real swaraj is not fought for, “we shall still keep their [the English] constitution and shall carry on the Government”, creating “English rule without the Englishman”.

He believed that “real rights are a result of performance of duty”. The same quote was recently used by Justice S.A. Bobde, the Chief Justice of India. Bobde said that it is implicit that legal rights have correlatives of legal duties. But instead of the traditional legal understanding that a right of a citizen leads to a duty of the State, the CJI, like Gandhi, said that a right of citizen is coupled with his/her fundamental duty to abide by the Constitution.

Quite predictably, this has led to a range of criticism. Commentators have asked for rights and duties to not be conflated in this manner. Rights, the argument goes, have their foundation in the essence of being human. Duties, on the other hand, may be necessary for building a family, community or nation but are not central to human existence. This is, at once, a correct understanding of the constitutional scheme, but a misunderstanding of what both Gandhi and Bobde said.

The chapter on fundamental rights has long been upheld as the charter of individual freedoms. Being one of the few parts of the Constitution not carried over from the British-era Government of India Act, 1935, it was certainly able to absorb global currents at the time. Those were heady times with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights coming into existence and new Constitutions being formulated in the Global South making promises of liberty and equality. The chapter reflects this zeitgeist in its bold declaration of the rights to life, personal liberty, equality before the law, a range of freedoms to speak, assemble, travel, trade, practise a religion of one’s choice and so on. Every Indian by virtue of his/her existence would have these rights.

But rights were not merely moral imperatives. They were also intended to be instruments that would make life better. Untouchability was abolished, reservation for backward classes was introduced, and material necessities such as medical care and basic education were read in by courts. Governments had the moral duty to respect these rights. However, it was envisaged in this scheme itself that governments would be recalcitrant. To offset this, an independent judiciary was institutionalized which would speak truth to governmental power and mandate compliance on behalf of the people. Citizens and governments were thus set up as hostile factions. Citizens would demand, governments provide and if they failed, courts would order.

This was in keeping with the finest American constitutional traditions that were built on a virulent scepticism of the State and militant liberty of individuals to do and act as they pleased. Despite its hoary moral foundations, the history of rights has not exactly turned out the way that was imagined, either in America or in India. A stark example is provided by the terrific recent TV series, When They See Us, about the real-life incident involving five black men who were framed by the state of New York for raping a white jogger in Central Park in 1989. The rights to free speech, fair trial, protection against double jeopardy all came a cropper against a racist police force and a justice system that was anything but blind to the colour of the accused. Justice was ultimately served only when the real rapist confessed to the crime over a decade later. By that time, the lives of the five men had been ruined almost irredeemably.

One instance is obviously far from enough evidence to bring down the entire edifice of rights. But it is demonstrative of one fact, which has been seen time and again — when governments are cast as rogues, they tend to be rogues. Worse still, when the moral duty of governments to provide is replaced with a legal duty to act when ordered, too much hangs on the faint sliver of an independent judiciary.

This is exactly what Gandhi was arguing against. If the ultimate goal of a nation state — and for citizens to come together to form one — is the well-being of the people, both the State and citizens must have duties in furtherance of this objective. The duties of individuals to be good citizens, have a sense of civic duty, do their bit to conserve the environment, are not absolved the moment a democratic State is set up. Instead, both the State and the citizens owe duties to each other. Neither did Gandhi nor Bobde make the pedestrian argument that to have rights one must perform these duties. Instead, the issue was “real rights” — the well-being of individuals that rights are intended to protect requires individuals to perform their duties as well. The State must provide for us but, at the same time, we must also provide for ourselves.

This is wound up closely with Gandhi’s understanding of means and ends. Simply insisting on rights would create a hostile State. Instead, the purpose of those very rights would be better achieved if individuals also resolved to be good citizens, capable of exercising such rights meaningfully. Bobde, too, in his seminal opinion in the Puttaswamy case adverted to this. He traced the right of women to have privacy from male strangers to passages in the Ramayana. This does not mean that having the right to privacy is contingent on any duties being performed. But for the right to be meaningful and effectively protected, there are duties all around.

The single-minded insistence on rights has meant that today we live in an age of tremendous freedom alongside alarming levels of surveillance and censorship. This paradox itself should indicate that all is not well in the citizen-State compact. Gandhi and Bobde have shown an alternative method of framing this compact based on rights and duties rather than on rights alone. As discomfiting as it might be to our modern sensibilities, we would do well to consider it.

The author is Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal