After a brief surge in the Lok Sabha election, the Congress appears to be floundering again. The shock victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party in Haryana is a close parallel of last year’s Madhya Pradesh election. In both cases, the incumbent BJP triumphed over the Congress despite a widespread anti-incumbency sentiment. So, what happened?

In an interview, Praveen Chakravarty, an aide to Rahul Gandhi and the head of the All India Professionals’ Congress, put forth an explanation. The Congress, he claimed, was hemmed in by a socialistic old guard and had lost the ability to cater to the “aspirational urban voter”. The evidence? The Congress won the majority of the rural seats (33 out of 65) while the BJP won the majority of the urban seats (18 out of 25) in Haryana. The diagnosis? The mistake lay in the Congress’s overemphasis on the message of social justice (caste census/Nyay schemes) to the exclusion of a market-centric entrepreneurial message. The solution? Proclaiming the message: “Making money is not bad… dream to be wealthy, go chase wealth, go chase money.”

The claim was confounding for two reasons.

First, no party in present-day India, not even the Left, proclaims that ‘making money is bad’. Chakravarty was not speaking of the Congress of the 1970s but of the architect of contemporary, liberalised India. The party campaigned under the leadership of B.S. Hooda (its prospective chief minister), who, in his previous terms, had instituted a model neoliberal government centred on developing the urban clusters of Gurgaon and Faridabad. In a case of coerced eviction of farmers, the Supreme Court had condemned the Hooda government for “the unholy nexus to promote the private interests” and overseeing the “transfer of resources of poor for the benefit of the rich” through “gross abuse of law”. He is hardly a wealth-averse, old socialist then.

Second, the trend of Congress trailing the BJP in urban areas stretches back to three decades, much before its backing for a caste census and the Nyay guarantees. Interestingly, a major exception was the 2004 Lok Sabha election when the Congress alliance trounced the BJP coalition in most urbanised seats. The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance infamously campaigned on the ‘India Shining’ while the Congress alliance channelised the material dissatisfaction of the ordinary man. The Congress routed the BJP in metropolitan Mumbai and Delhi as did the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party in cities across Uttar Pradesh by appealing to the non-elite sections that form the vast majority of the urban population. The rural and urban life-worlds are by now tightly bound, representing a continuum, not binaries.

Nevertheless, the comments made by Chakravarty are quite instructive. They provide a window to understand a certain worn-out political imagination plaguing the Congress. Take, for instance, Jairam Ramesh, a senior strategist of the Congress, who remarked to the political scientist, Anuradha Sajjanhar, that “we’re in a post-ideology world.” The following excerpt is taken from Sajjanhar’s recent book, The New Experts, on the country’s technocratic governing elites. Unlike Chakravarty, Jairam Ramesh is a central decision-maker shaping the party’s direction.

“Researcher [Anuradha Sajjanhar]: What do you mean by that [post-ideology world]?

“JR [Jairam Ramesh]: Where ideologies do not drive political parties… That era is over. Ideology drove Thatcher. Ideology drove Reagan. After that, finished. Ideology drove the Labour Party. Ideology drove Nehru. Indira Gandhi was not an ideologue… people are less ideological today. Ideology doesn’t drive discourse, the time that used to happen in the 40s and 50s… We keep using the phrase ‘party ideology’, but I don’t see ourselves [that way]. I see us having a dominant social ideology, but I don’t see us having a dominant economic ideology. Our economic ideology is a little more pragmatic, you know.”

Typical of Anglophone elites, Jairam Ramesh finds it hard to see a world beyond Thatcher and Reagan. Might we take a glance at South America, which is closer to us in its stage of development and faces similar socio-economic challenges, to see if we are indeed living in a post-ideology world?

We just had a presidential election in Mexico where Claudia Sheinbaum, of the left-wing Morena party, won a landslide victory. The party was formed by her presidential predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, just over a decade back. Today, it enjoys majorities in both houses of the legislature and controls 23 out of 32 state governors.

Obrador had broken away from the established Centre-Left Party of the Democratic Revolution after losing a presidential election. Subsequently, he took control of Morena, a party built from the bottom up out of civil associations and social movements. The ‘pragmatic’ PDR, a rough equivalent of the Congress, welcomed the divorce, branding Obrador as too polarising for courting independent-minded voters. After all, Obrador promised a sharp break from neoliberalism, instituting democratic control of the economy in favour of the non-elite. As it turned out, the radical agenda not only won him the presidency with majority support but also virtually extinguished the PDR from the political map.

Or let’s take the case of the Brazilian Worker’s Party (PT), formed out of labour and activist movements in the 1980s, which has governed the country for most of the 21st century. The PT, led by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, represents a much more institutionalised party than the personalistic Morena. Yet it is formed on the same organisational principles as Morena — a lean bureaucratic core, stringing together a constellation of labour movements, peasant organisations, indigenous groups and urban-civic associations. This affiliate structure of party-building is an altogether different (and more adaptable) creature compared to 20th-century Europe’s mass-based labour parties. The concept of a party-field is useful here, denoting a network of allied groups rather than a hierarchical, tightly-wound organisation. The left-wing Movimiento al Socialismo party of Bolivia and the Frente Amplio of Uruguay, too, are structured along broadly similar lines and have also dominated their polities for the last two decades.

All this has happened in the same timeframe which Jairam Ramesh flippantly describes as the post-ideological era. Forget South America. In our own immediate South, the left-wing, populist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna of Anura Kumara Dissanayake has upended the political system in Sri Lanka, winning the recent presidential election with a landslide. Dissanayake campaigned on tropes that are remarkably similar to those of Obrador, linking economic austerity and social insecurity to a corrupt system run by incestuous economic and political elites.

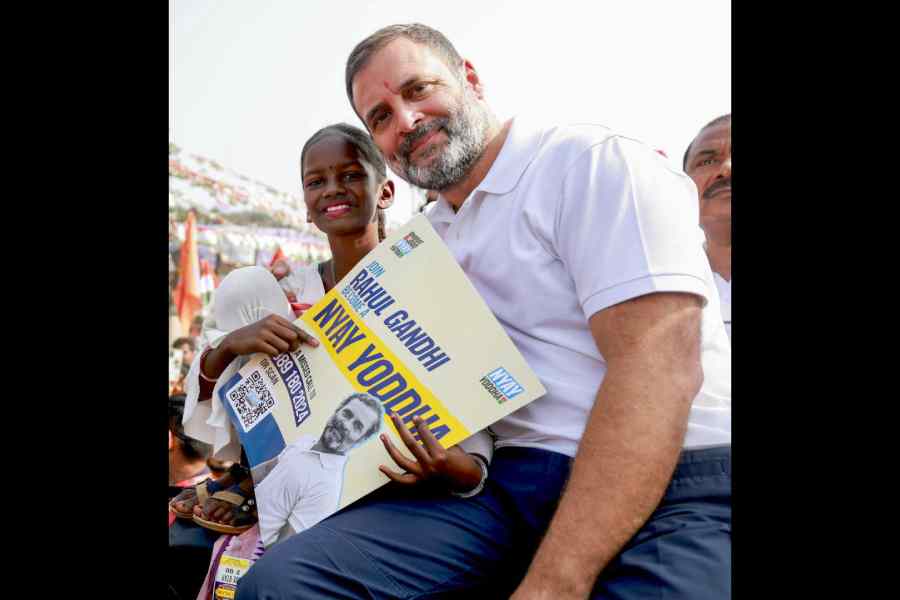

In this respect, the Congress’s path towards victory in Telangana could have provided the contours of a model. A raft of splits and defections had left the party with a moribund organisation. Yet, in the year before the election, the state Congress mounted a spate of hectic mobilisation involving partnerships with Dalit and tribal social movements and networking with veteran statehood movement activists. This process was supercharged by the Bharat Jodo Yatra. Subsequently, political and business elites flocked back to the Congress, culminating in a remarkable turnaround.

However, we have seen the Congress previously use activist movements as disposable commodities, employed for election management. A good example is the 2018 victory in Chhattisgarh, where the party was aided in mobilisation by tribal activists. After gaining office, it dumped the activists and pursued the usual exploitative economic model run by a bevy of bureaucrats around the chief minister. Unsurprisingly, they received a fatal tribal backlash in the next election.

Parties like the PT in Brazil cultivate long-term, organic linkages with their activist bases, including them in policy planning and implementation and providing them with patronage. Thus, they manage to build self-sustaining organisational structures constructed around a shared ideological vision, possessing a loyal mass-base which identifies emotionally with the party.

The persuasive thesis of Sajjanhar’s book is that India’s political culture has become trapped between populist identity-politics and a “technocratic” governing paradigm. The former makes rhetorical appeals to religion/nationalism or caste/region. The latter remains yoked to a “pragmatic” ruling “consensus”, exemplified by leaders like Jairam Ramesh. As the economist-philosopher, Karl Polanyi, stated, people look up to a welfare-State to protect them from the ravages of the iniquitous market-economy. The Congress needs to offer a protective political model to ordinary people who are struggling economically instead of mouthing fairytale slogans.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist