My first exposure to European painting was through the plates of reproductions in books that my parents had bought. My parents were not wealthy, these foreign books were not cheap in the 1960s, and we only had two or three slim volumes, one about Rembrandt, one to do with van Gogh, and then a tiny, slim, pocket book about Monet from a series on the Impressionists. We also had one framed reproduction that hung on a wall near our dining table, gifted to my parents by someone who’d come back from abroad, Rembrandt’s Bathsheba lifting her white shift while entering a pool of water. As a child, the amazing sensuousness of this painting was completely lost on me — all I saw was a woman, an old woman as I always thought of her, wading into possibly cold and wild (and therefore quite likely dirty) water. This Bathsheba reigned over my Gujarati meals and tubelit efforts at homework. The van Gogh caught my attention because of what I thought was the ‘rough’ drawing and painting, but I loved the colours, such as the reproductions of the time had caught them. The little Monet booklet came into the house when I was a little older. It was from a later generation of offset printing and the colours were brighter and more exciting; this was the book I found myself looking at more and more and it was these pictures that I tried to emulate (not copy, because what did I have to do with sailboats, snowscapes, haystacks, the changing colours on the stonework of a cathedral?) when I began to try my hand at painting.

The first lucky trip to France at the age of 15 brought me face to face with some of the originals and it was a shock. The scale was different; you could sometimes see the shadows of the thickly applied brushstrokes; the colours were somehow both brighter and yet more matte (the paper used for the reproductions in the books had a shine), you could see all sorts of little marks and ‘mistakes’ that photographs of the paintings just didn’t catch. Monet’s Water Lilies series surrounded you in a way they never could from a book; the Rembrandts had a depth in the blacks and deep browns that was completely lost on paper; the van Goghs had a rawness and a violence that was smoothened out in even the best reproductions. By that time my horizons had widened and I took in not just the older masters but also the recently deceased Picasso and other later painters. If the Rembrandts and Monets had multiple layers that reproductions did not reveal, reproductions also wrong-footed you about a painting such as Guernica and the immediacy of the slashes of paint that fought across the canvas — the reproductions brought the eye to equate Guernica’s blacks and greys with Rembrandt or Vermeer’s shadows, which was totally wrong. You realized as you looked at these originals that each painting was also, in a sense, a sculpture, with the three dimensionality of the canvas, the texture of the paint, the frame or the absence of one, the way the light changed on the surface depending on where you were standing, who was standing between you and the image cutting off a bit of it, and so on.

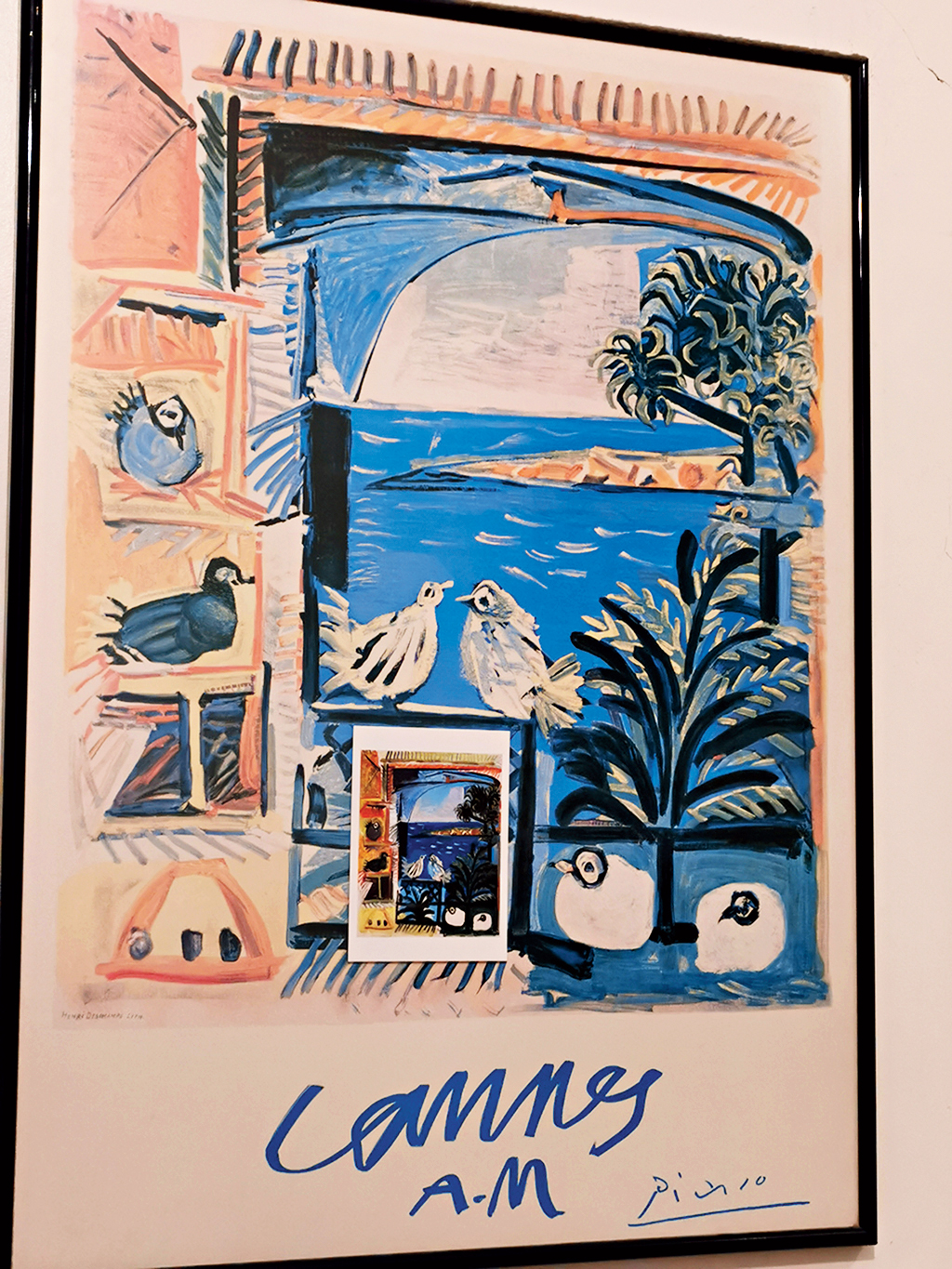

And yet, you felt the greed or the hunger, to carry some of the images back with you to India, to have them in your flat to look at every day. And therefore grew the collections of posters in so many of our apartments, every trip abroad adding more, one or two, as per affordability and mobility, till a certain section of people had their walls covered with the usual suspects: Western painting from the 17th century to the late 20th, that dove by Picasso, those sunflowers by Vincent VG, that photo of Che Guevara, and stills and posters from favourite cinema classics from Eisenstein and Fritz Lang to Almodóvar and Tarantino. The cinema posters and political ones are perhaps a whole another story, but, over the last forty-odd years the posters of paintings have proliferated and become a central part of the housescapes of a certain section of cosmopolitan Indian intellectual/rasik.

Recently, I found myself looking at a formidable exhibition of the later works of Francis Bacon at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Made mostly after the huge Paris retrospective of his work in 1971, these are some of Bacon’s most famous, iconic images. I’ve seen Bacon paintings ‘in the flesh’ before, so to speak, but never a concentration of such a large body of his canvases. The thematic conceit of the show was interesting, solid, pegged around books that were important to the painter who was apparently a voracious and obsessive reader. Texts by Aeschylus, Nietzsche, Conrad, Eliot, Michel Leiris and Georges Bataille were given pride of place, rooms devoted to each relevant book, like text-oases, spaces where you could just sit and listen to recorded readings punctuating the maze of images, with the paintings arranged thematically rather than chronologically. One of the many things that struck me though was how immersed you became in the vernacular of the brushstrokes, in the flat fields of colour interrupted by the highly controlled brawl of marks, gobs of paint, thick and thin playing off each other, precise, masterful draughtsmanship dancing with sections that are as freely chaotic as anything by a de Kooning or Pollock. That and the scale of the large works, with the triptychs working as visual force multipliers, all ganging up to pull you into Bacon’s particular dystopic universe.

Before seeing this show, if someone had come back from abroad bringing me a poster of a Bacon painting I would have been very happy. After seeing it, I realized that I’m happy to have my Francis Bacon reproductions contained to books and postcards. In those, you get what I call the ‘thumbnail effect’, where the images are compact and complete, each one coming at you as a small, digestible whole, with no pretensions to competing with the much bigger original. Walking through the museum shop, I left the exhibition merchandise untroubled, not even tempted to pick up a fridge magnet as a gift. This lack of temptation isn’t the case with every painter or every exhibition, of course, for there are some reproductions that get through to you for just what they are, beautiful, alluring, satisfying in their own right.

Coming down from the higher floors of the museum, passing the galleries which hold the Pompidou’s permanent exhibits, I thought of all the many faded posters of Western paintings I’ve seen on the walls of friends’ houses. Some of the old prints are so far gone they bear almost no relation to what you could see when they were first purchased. Many of the faded stretches of paper now invite a layering intervention from some contemporary and un-famous hand, but you can only suggest this to the proud owners at your own peril — the images hanging on the walls have little to do with what van Gogh or Monet might have intended and everything to do with the poster-purchaser’s memory of that moment where they felt they had partly possessed a favourite work of art.

One such friend will not listen to my entreaties that he must either throw away the old faded prints or let some of us friends draw on them. One of the faded posters this friend hangs on to is from Picasso’s 1958 series of paintings of dovecotes against the blue sea at Cannes. Recently my friend was away when his son returned from Spain bringing back postcards of the whole series, freshly printed and rich in Picassoian colour. He and I went through the lot and found the postcard of the same painting as the large faded poster on the wall. We quietly and discreetly stuck the postcard on to one section of the poster, sort of like a small Russian doll hiding within a larger doll. We decided not to say anything to my friend when he returned and to wait and see if he noticed someone had tampered with his favourite Picasso poster. It’s been a few days, the post-card is still there and the friend hasn’t noticed anything.