It is like a mise en scène of a cinematographer preparing to shoot the Ayodhyakanda. The edges of the paper on which the “storyboard” was made are frayed, the paper itself has yellowed, but the line drawings are still very clear. Elaborate scenes. King Dasaratha trying to find out what is wrong with Queen Kaikeyi. The queen sitting in front of him, expressing her wish that Rama be exiled. Dasaratha arguing. Dasaratha lying down. Kaikeyi holding ground. The main drama is enacted in the rooms of the palace. It is to be appreciated how the artist has taken care to sketch the humdrum life, in and around it. Two women chatting on the terrace. Two others singing. Horsemen and elephant-riders going about their tasks. But wait, this is no cinematographer’s storyboard. It is a drawing from a folio of the Pahari art form fished out from the deep recesses of the Kasturbhai Lalbhai Collection only recently by Professor Ratan Parimoo.

The Pahari School Ramayana Drawings of Ayodhya Kanda — a group of 62 folios of line drawings — unfold a day-to-day account of the dramatic events of the Ayodhyakanda. Parimoo, who is currently director of the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum in Ahmedabad, was in Calcutta not long ago. A veteran art historian and a painter himself, Parimoo gave an illustrated talk at the Victoria Memorial Hall, wherein he described Pahari art as a form akin to the cinematographer’s storyboard.

The well-attended talk had among the audience art critic Pranabranjan Ray. He chaired the session and launched Parimoo’s book, From the Earthly World to the Realm of Gods, Kasturbhai Lalbhai Collection of Indian Drawings.

The collection of folios was put together by artists Gaganendranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore between 1900 and 1915. They were subsequently assisted by E.B. Havell, the then principal of the School of Art and Craft, Calcutta, which later became the Government College of Art and Craft. Havell had established a full-fledged Indian Art Gallery at the School of Art and Craft, replacing copies of European art with original Indian paintings, stone sculptures, metal objects and textiles. His collaboration with the Tagore brothers, however, ended in 1905, which is when he went to England and was not allowed to return because of his anti-imperialist stance.

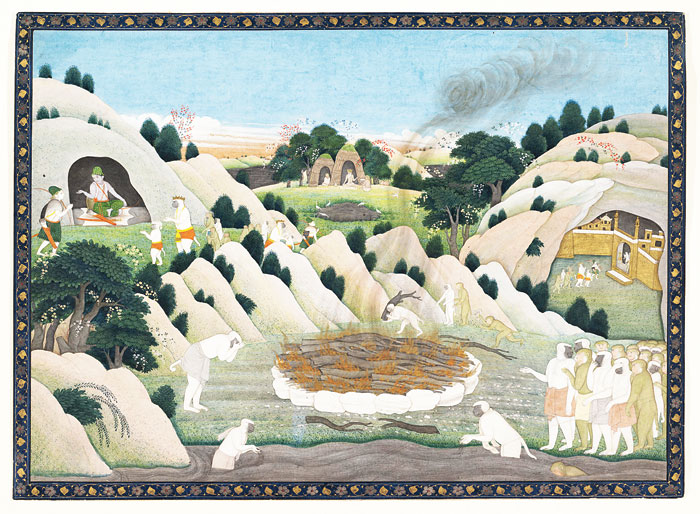

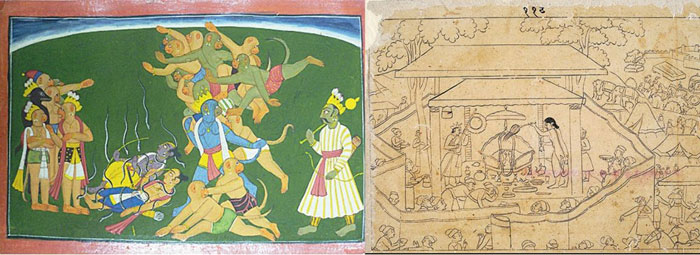

Two examples of finished Pahari Ramayana paintings from the British Library and the Metropolitan Museum in New York British Library, Metropolitan Museum in New York

Later, the pioneer historian of Indian art, Anand Coomaraswamy, collaborated with the Tagore brothers. “Impressed by the Tagore collection, he started his own collection of Indian art. He also influenced the Tagore selections. He made drawings and wrote on Rajput paintings,” says Parimoo by way of an aside.

In 1928, once Gaganendranath fell ill, Abanindranath became nervous about the fate of the collection and wanted that someone should come forward and set up a museum, narrates Parimoo. It is at this juncture that Seth Kasturbhai Lalbhai, a Gujarati industrialist and art patron of Ahmedabad, was approached. “A daughter of the Hutheesingh family of Ahmedabad was married to Rabindranath Tagore’s brother’s son. This Gujarati daughter-in-law, Srimati Tagore, approached the Kasturbhai Lalbhai family to take over the collection and turn it into a gallery,” says Parimoo.

The Kasturbhai family had two branches; the collection was divided up between them. Parimoo continues; “They kept masterpieces like the bronze and stone sculptures, finished miniature paintings, Buddhist sculptures, Tankhas or Tibetan Buddhist paintings, a monumental Tara sculpture. The rest they donated to the museum.” The outline drawings, which the family thought were B-grade, were given to the museum.

Parimoo talks about the 18th century German writer and art critic, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and what he said about “space art” and “time art”. According to Lessing, space art includes painting, sculpture, architecture. Time art includes the performing arts, theatre, literature. Lessing’s distinction between the two forms do not hold for Indian painters in that they attempt to capture the continuity of an event, says Parimoo. He calls the style pictorial narratology and says, “The artists of this set of Indian art go beyond Lessing’s space and time art distinction.”

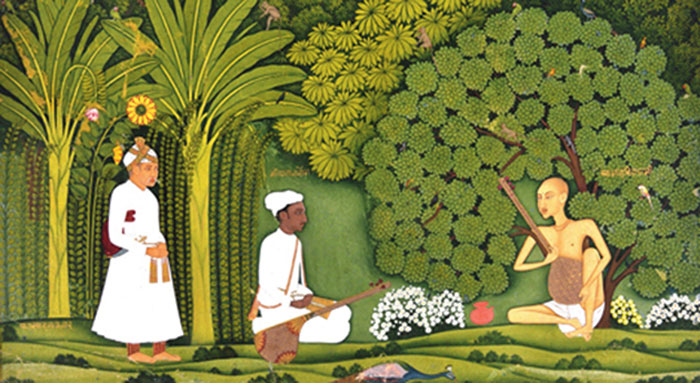

Akbar and Tansen, in disguise, listen to Swami Haridas National Museum, Delhi

And Parimoo is back on the topic of the Tagore collection. He compares the collection with that of the Bharat Kala Bhavan at Benaras Hindu University. The Benaras folio has paintings by Nayansukha and Ranjha, a father-son duo. The Tagore collection, however, has no names of artists. Says Parimoo, “Gaganendranath’s set is very close to the Benaras set.”

Another interesting drawing from the folio is one where Shatrughna literally hauls up Kaikeyi’s whisperer, the hunch-backed Manthara. It is a tragi-comic scene. Bharata and Shatrughna arrive in Ayodhya. Bharata asks his mother to explain why she wants Rama exiled. According to the text, Kaikeyi tells him about Manthara’s advice, and suddenly all is bedlam and chaos in the palace. Each sketch in the Ayodhyakanda collection comes with a descriptor. “From the brief summary, an elaborate composition was done. That’s why these paintings are also called the painter’s Ramayana,” explains Parimoo.

As he talks about the significance of the collection, the 83-year-old says, “While collecting these sketches, the Tagore brothers were themselves trying to understand the miniature painting technique. When people see the line drawings they will say to themselves — ‘I saw this is in London or Paris’.”

The professor explains, that’s because these sketches are the master drawings of many finished paintings that are now dispersed widely in the collections of many international museums, including the British Museum.

Parimoo continues, “These sketches have artistic and practical significance in the practice of painting. In the National Museum in New Delhi there is a Rajasthani miniature, wherein Akbar is represented in the company of Tansen. Both are in disguise and they are listening to Haridas [Swami Haridas, the Vaishnava singer and poet]. We have an outline drawing of that in our collection. So our outline drawing is the master drawing.”