Federico Fellini was born a hundred years ago this January. From the mid-1950s on, Fellini made some of the greatest films in the history of cinema. He began work in the ruins of post-Second World War Italy and his best films came across the next 20 years as Italy recovered from the long catastrophe of fascism and kick-started its economy while producing some of the most powerful and liberating cinema the world has known.

When we celebrate the man, we actually celebrate several Fellinis: there is the young man who co-writes the scripts of Rome, Open City and Paisà with Roberto Rossellini, contributing to the beginning of the Italian neorealism movement; there is the novice director who finds his ‘hand’ with I Vitelloni and La Strada, still paying his dues to neorealism; then come the films for which he is best known, among them La Dolce Vita and Otto e Mezzo (Eight and a Half), which are amazing depictions of an Italy grappling with a sharp class divide, consumerism and the depredations of modern media. After this come more films but the last great one is the autobiographical Amarcord made in 1973, which is a gut-splittingly funny, moving, cine-song to his childhood in the small town of Rimini on Italy’s east coast.

Unlike other contemporary Italian directors, Fellini was never overtly political. He always said he was more interested in how the individual dealt with society and history and the absurd, the surreal, nostalgia, longing and desire all played a central part in his oeuvre. Certain things stay constant across forty plus years of work: Fellini hated Mussolini and his fascist ideology, viciously lampooning the toxic self-regard, buffoonish pomposity and murderous violence fascism produced; in the home of Catholicism, he never failed to laugh at the hypocrisies of the Church, while fully enjoying the good things in life, Fellini was viciously precise in how he caught the wealthy and their criminal selfishness.

Today, if one was to introduce Fellini to a younger generation of Indians who didn’t know his work, with just three sequences from his films, which ones would I choose?

The first would be the opening sequence of Eight and a Half, where the protagonist film director is sitting in his posh car in an underpass, caught in a traffic jam. The man looks around and sees other people trapped in their own vehicles; he sees a bus with passengers so tightly sardined that their arms hang out of the windows as though they were cadavers. As he starts to wipe the windscreen, smoke begins to pour out of the car’s air vents. The man tries to open one door, then another, but to no avail — they are jammed and he is being gassed. People in the adjacent cars watch him with mild interest as he struggles for breath but no one tries to help him. One person, turned in a rear seat, shows slight concern but, again does nothing. In another car, a man is totally focused on caressing a woman’s bare shoulder. The protagonist’s fingers squeegee against the locked windows, the soles of his shoes upend on the seat. Zombie-like passengers watch from the bus. Finally, the man manages to escape through the roof-window and get on top of the car, before floating away over the unmoving traffic.

In less than two minutes, we have a prescient rendering of today’s urban reality with our obscene automobile obsession and endless traffic jams. We also have a clear metaphor for what is happening in so many of our societies, where all empathy is disabled and one can watch without moving as someone struggles for life in the transparent box next to one’s own. Looking now, the violent death implied in the upended shoes brings you straight to Francis Ford Coppola’s homage in the garroting scene in The Godfather, and past that to all the violence and assassinations of our own time.

The opening sequence of La Dolce Vita has also become part of cinema lore. Two helicopters whirr across some old ruins and then swing over the city of Rome. Suspended from the first helicopter is a big statue of Christ with paint that shines in the sunlight. The second helicopter, we soon realize, carries a journalist and his photographer. The choppers cut across over working-class neighbourhoods where kids chase them as you would a kite in an Indian town, over acres of new construction where the working labourers look up and wave, over a rooftop swimming pool next to which four young women in bikinis sun themselves — “Look there’s Christ!” — over the Vatican where the crowds have gathered, everyone looking up, everyone waving. Again, a few shots encapsulating the reality of a society: the poor, the workers and the idle rich over which hover the spectacle of religion and the parasitical media.

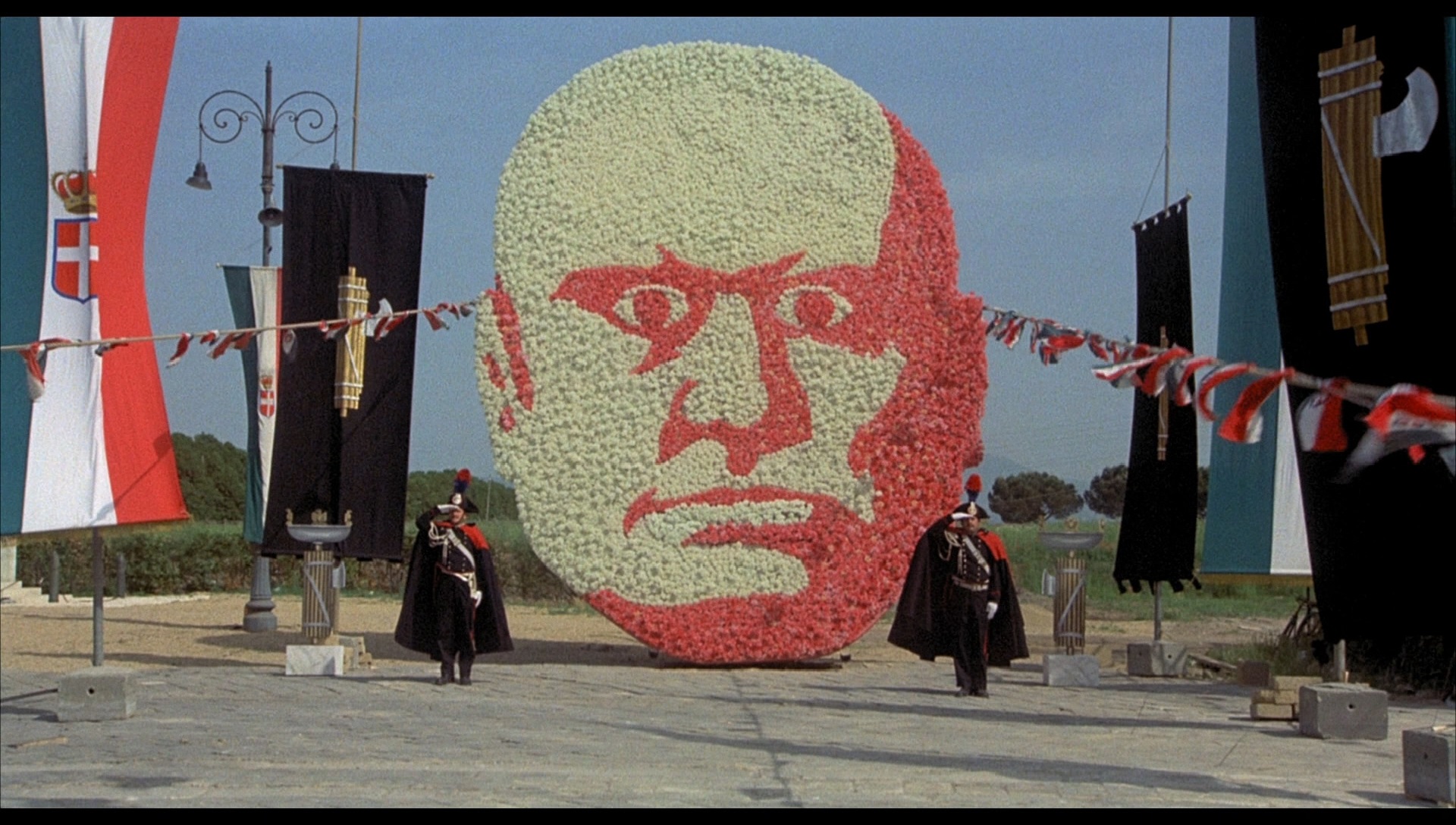

The final sequence I would choose is from Amarcord, where the small town awaits the great fascist leader Mussolini to make an appearance. The soldiers are in parade dress, standing rigidly to attention as are the police; the clergy is ready with their crosses and censers; the crowd is restless, some men push out their chests, some women are beside themselves in an ecstasy of anticipation; the photographer, head already under his sheet, has pride of place in the middle of it all. Someone calls out, “He’s coming!” People take up the chant. The passageway from which Il Duce will emerge on to the square fills up with what looks like grey car exhaust. People cheer as uniformed figures solidify in the smoke. The group of men, with a Mussolini lookalike in the middle, jog into the square, preening even as they prance past, showing their fitness. People throw their hands up in the fascist salute; a woman screams, “Let me touch him! I want to touch him!” As they jog along, various local leaders gasp out their reports. “99 per cent of the population are members of the Fascist Party!” and “This marvellous enthusiasm makes us young and yet so old at the same time! Young, because Fascism has rejuvenated our blood! With glowing ideals from Ancient times!” Another jogging chamcha mutters in wonder, “All I can say is Mussolini has two b**ls this big!”

The group goes up a flight of steps, stops and turns. An official addresses the crowd: “Do we not see on this glorious sun-filled day that the Italian sun, forever free, is a divine sign the heavens are on our side?” The crowd screams its salute.

Soon the lookalike (a bald man with close cropped sides is, after all, a bald man) and his cohorts are erect on a stage, hands locked on gunbelts. Facing the stage, boys in black shorts and singlets perform synchronized calisthenics. Girls in ladylike dress perform hula-hoop exercises. A massive animated mask of Mussolini appears. A plump boy in his singlet and shorts is about to get married to a girl with a veil. The lips of the mask open and shut as a disembodied voice pronounces the vows. In a quiet street nearby, a man tries to open the gate of his house. His wife, who has locked the gate, refuses to let him out because she knows he wants to go to the town square and protest. “If I wanted you dead, I would kill you myself!” she says. “You think I’m scared of those black-shirted lice?” he thunders, but she doesn’t budge.

I suspect there would be no need to explain the relevance of this third sequence, even to young Indians new to Fellini.