India has made a concerted bid to focus international attention on global security issues, especially terrorism. In the space of a month, between October 18 and November 18-19, it hosted the General Assembly of the Interpol, a special meeting of the United Nations Security Council’s Counter-Terrorism Committee, and the third ministerial conference on ‘No Money for Terror’. India may also emphasise counter-terrorism during its rotational presidency of the UNSC this month.

These efforts to ensure that terrorism remains high on the international agenda are being made at a time when its salience has diminished in the security calculus of other major powers. Their attention is committed to the Russian invasion of Ukraine with its adverse impact on international — especially European — security and global supplies of energy and foodgrains. Besides, neither the United States of America nor China, the world’s foremost contemporary nation states, feels truly threatened by terrorism. The former has displayed the capacity to take out specific targets as demonstrated by its killing of al Qaida chief, Ayman al-Zawahiri, in Kabul on July 31, while China has the Uighur situation, which has manifested itself through occasional terrorist acts in the past, well under control through the use of the most drastic means.

Of all the major powers, it is only India for which terrorism continues to be of the greatest concern; its desire that it remains a most important priority in the global agenda is, therefore, entirely understandable. The pertinent question now is whether India will succeed in the ambition expressed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the conclusion of his November 18 inaugural address to the NMFT conference. Modi said, “Our intention is to bring the world together in taking the war against terrorism to the next level.” The intention is laudable and should be pursued. However, prudence demands that the expectations of outcomes should remain modest.

Modi’s speech at the NMFT conference was a fine exposition of the damage terrorism causes to global society. He put it well when he said that the victims of terrorism are not only those innocents who are killed and maimed but also those whose livelihoods are adversely impacted by it. As he put it, “Be it tourism or trade, nobody likes an area which is constantly under threat. And due to this, the livelihoods of people are taken away. It is all the more important that we strike at the root of terrorist financing.” More specifically, without naming Pakistan or China, Modi targeted them for their role in either promoting or shielding terrorists. Modi said, “Certain countries support terrorism as part of their foreign policy. They offer political, ideological and financial support to them.” This is a position India has taken for over three decades with regard to Pakistan’s promotion of terrorism in India. The major powers have been fully aware since the 1990s of Pakistan’s use of terrorism against India and also of it giving sanctuary to global terrorist leaders. However, they have acted against Pakistan in the terrorism context only when such action has been warranted by their overall policies on Pakistan and the region. The way Pakistan was grey listed under the Financial Action Task Force and taken off the list recently establishes this point. Under FATF pressure, Pakistan took some steps against some anti-India terrorist groups but these have only been cosmetic. Every major power is aware that Pakistan has not attempted to eliminate anti-India terrorist groups. It continues to nurture them even as they calibrate their attacks on India.

Thus, Modi is right in exhorting the world “to unite against all kinds of overt and covert backing of terror”. But sadly, this is unlikely to be so. His remark, “There is no place for an ambiguous approach while dealing with a global threat”, applies to China, which has shielded, on untenable grounds, known Pakistani terrorists from becoming designated under different UN instruments. China’s nexus with Pakistan ensures that it will continue to shield the anti-India terrorists harboured by the latter. Besides, it is unlikely that the US will now be willing to pull out all the stops as it once did with China for designating the Pakistan-based Jaish-eMohammed terrorist organisation leader, Masood Azhar, as a UNdesignated terrorist.

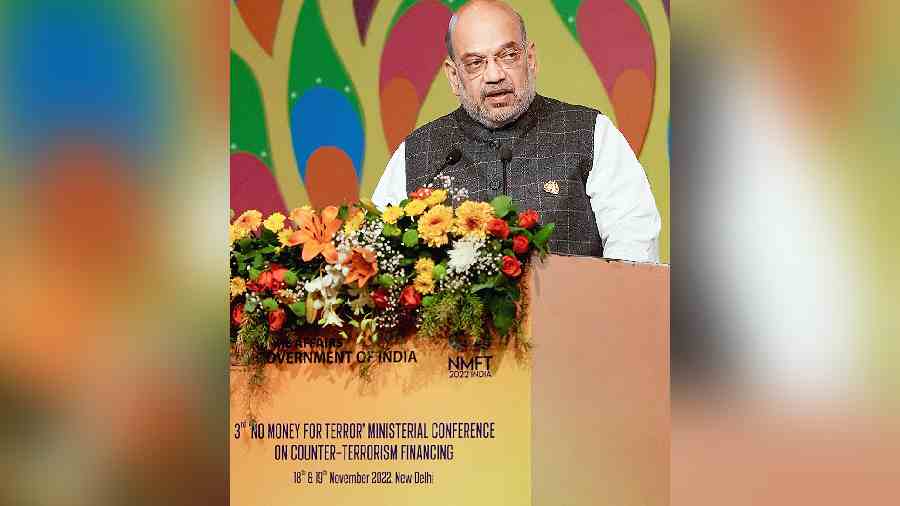

In his concluding remarks to the NMFT conference, the Union home minister, Amit Shah, reiterated Modi’s appeal to the global community to come together to combat terrorism, including through the choking of its financing. All that Shah said was incontrovertible in principle but there are two issues which require a realistic appraisal from the criterion of practicability. The first was his appeal that “all countries will have to agree on one common definition of ‘terrorism’ and ‘terror financing’”. Sadly, the experience of negotiations on the Indian proposal to the UN’s General Assembly on a ‘Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism’ that was submitted in 1996 shows that the international community has simply been unable to agree on what constitutes terrorism. Instead, it has focused on acts of different kinds which it has considered as terrorist in nature. Thus, it may be futile in the foreseeable future to expend diplomatic capital and energy to find a universally acceptable definition of terrorism, howsoever laudable such a quest may be in principle. Instead, it would be appropriate to focus on terrorist acts that countries like Pakistan undertake as State policy. This would apply also to seeking a definition of ‘terrorist financing’. The emphasis should be more on cutting the flow of funds to violent and terrorist groups through global cooperation on the basis of steps outlined in Shah’s speech.

The second point that Shah suggested was the establishment of a permanent secretariat to anchor the NMFT’s efforts. As he put it, “During the deliberations, India has sensed the need for permanency of this unique initiative of NMFT, in order to sustain the continued global focus on countering the financing of terrorism. Time is ripe for a permanent secretariat to be established.” India now seeks to take this suggestion forward by circulating “a discussion paper to all Participating Jurisdictions”. Diplomatic experience shows that the effectiveness of efforts does not depend on the creation of international bureaucracies but on the will of concerned countries in taking initiatives forward. And their will depends on their evaluation of their national interests. Naturally, it can be expected that India will carefully study the responses of the countries before proceeding forward with its idea of establishing a permanent secretariat for the NMFT, especially because it is never easy to work out the details, including the role of such secretariats. Besides, they often generate their own dynamics which are not necessarily helpful to take the objectives of the efforts forward.

Predictably, Pakistan saw in the convening of the NMFT conference in India an attempt to denigrate it and point fingers at its involvement in terrorism and its financing. Pakistan’s fulminations against India can be ignored, but not its keeping terrorism as part of its strategic doctrine against this country. What cannot also be overlooked by India is that despite all their fine words, the major powers continue to maintain a segmented approach against terror. The lesson of the past three decades is that India has to continue to rely on its own defensive and offensive strategies to combat terrorism.

Vivek Katju is a retired Indian Foreign Service officer